How This California Town Became a Model Community for Black Americans in the Early 1900s

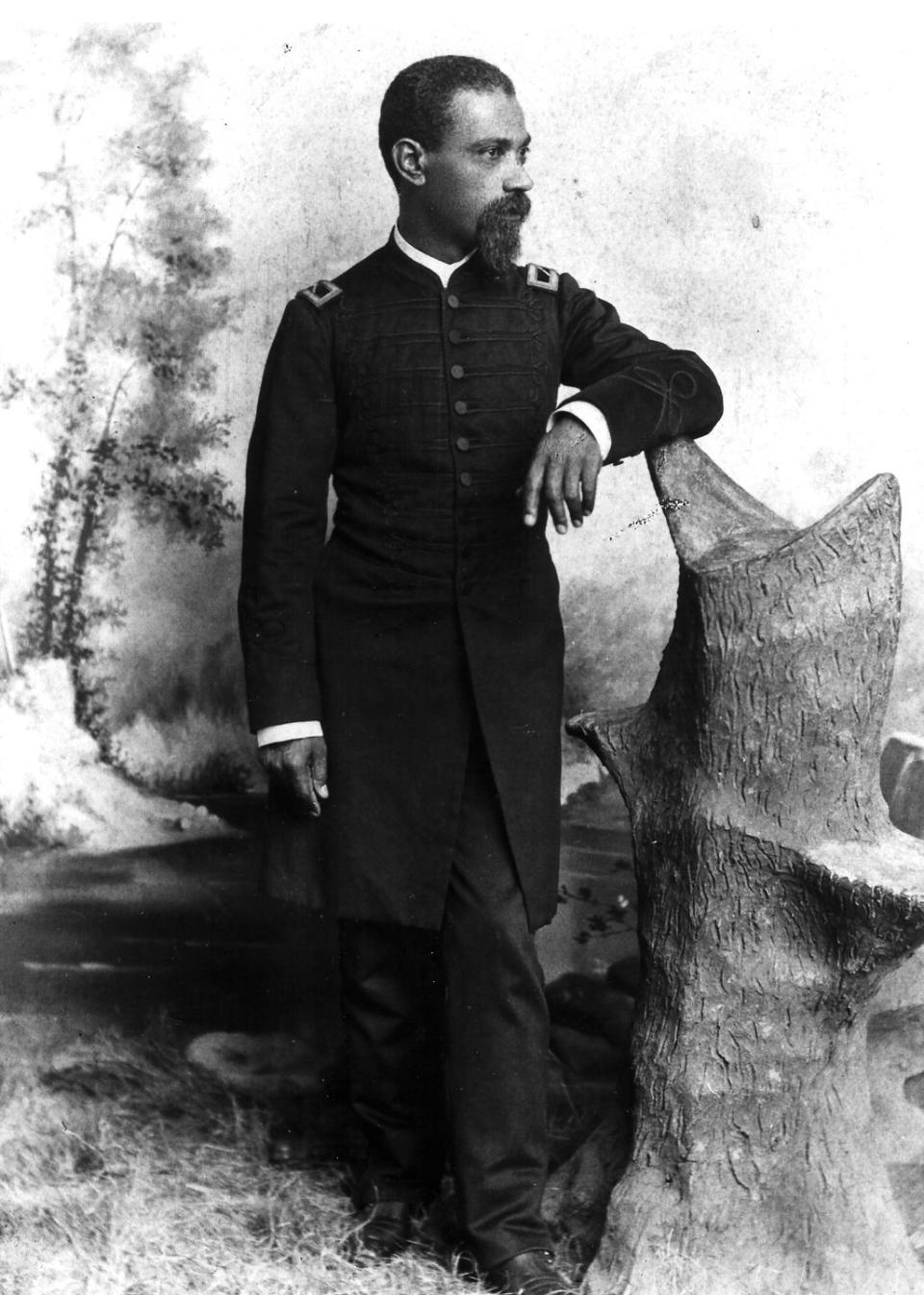

Like many other Black people in the early 1900s, Colonel Allen Allensworth yearned for a place where he could live his best life. So he decided to do something about it: The formerly enslaved man and decorated veteran teamed up with educators and entrepreneurs to found Allensworth, a model California community just for Black people in 1908.

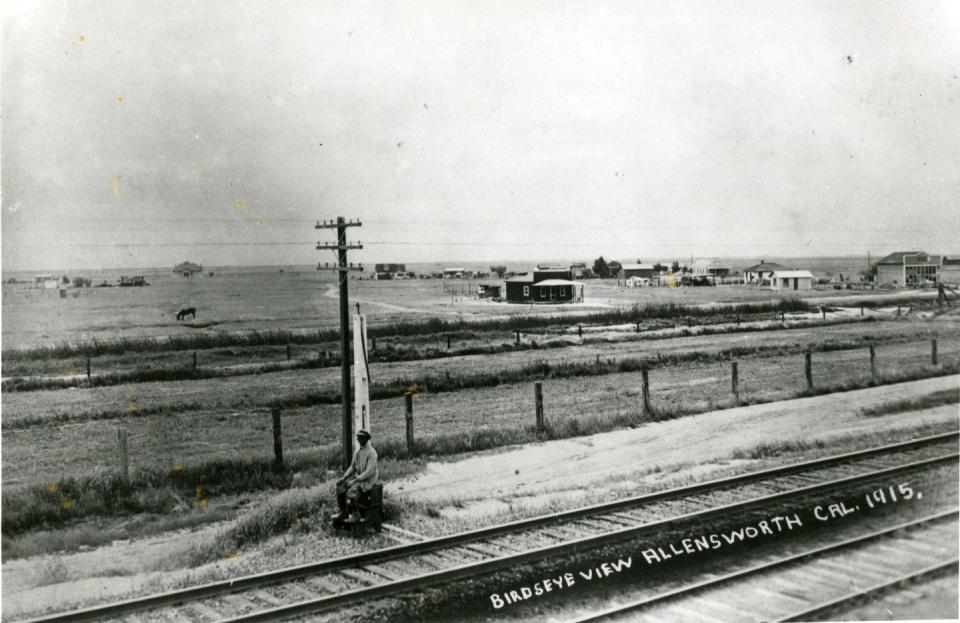

Allensworth was designed as a self-contained community with its own voting precinct, schools, justice of the peace, and constable. It had a Santa Fe train depot that brought visitors and commerce to the town, acres of fertile farmland and assurances of plentiful water to ensure the town’s growth. Allensworth thrived for a time, attracting as many as 300 residents, and then dwindled due to a series of devastating blows.

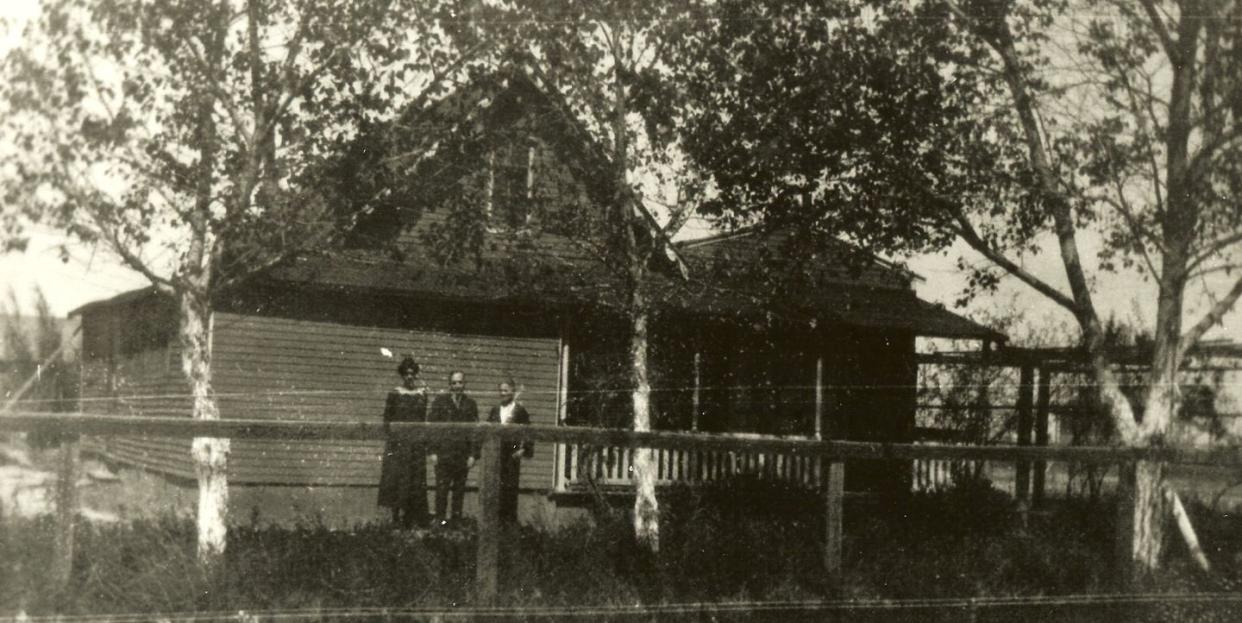

But more than 100 years later, there’s resurgence in interest in Allensworth, the only Black utopian town ever founded in California. The heart of the town, including the Colonel’s home, the general store and school, are now part of the California State Parks system. While in-person tours are on hold due to COVID-19 concerns (the park is open for day or overnight visits), teachers are keeping state park interpreters busy with Zoom tours and talks about Allensworth. And more than 1,300 people joined a Black History Month Zoom presentation about the town in February 2021.

“I think the reason why it’s so enduring is because our country wants to preserve these places, and there is still a conversation going on about race in the United States,” says Lori Wear, California State Parks interpreter II. “These people came and were successful and through no fault of their own they suffered setbacks.”

Former soldiers from Black regiments, business people, and families who wanted a different life moved to Allensworth. They raised cattle and rabbits, and grew alfalfa, sugar beets and corn. The town’s streets were named for accomplished Black people including poet Paul Laurence Dunbar, Revolutionary war hero Crispus Attucks, and abolitionist Sojourner Truth.

Residents bought kit homes and set them up north to south, to capture a nice cross breeze in the afternoon and evening. “The houses came in on the train. They ordered them from Sears and Roebuck,” says Sasha Biscoe, president of Friends of Allensworth. “Back then, Sears was the only company that would sell to Black people.”

Downtown bustled with a barbershop, the Singleton Store (which also had a post office), and the Hindsman Co. general store for coffee and tools. The scent of fresh bread from the bakery tempted visitors as they stepped off the train. A night out meant dinner at the Smith House, where Mrs. Smith served her specialties in her living room, or the Allensworth Hotel dining room.

The town had large annual Fourth of July and Christmas celebrations and social activities year round like Glee Club, Debating Club, and the Women’s Improvement League. Many residents enjoyed playing pianos and woodwinds or singing. “Allensworth had a baseball team that played teams from nearby towns,” says Jerelyn Oliveira, state park interpreter I with California State Parks.

There was nothing like Allensworth in California or the rest of the US, according to Steven Ptoemy, supervisor of the Cultural Resources Program with California State Parks. “There were many Black towns, but … it was a complete township, even though it was not incorporated,” Ptomey said in an interview with the Fresno Bee, “and that’s unique."

By 1910, national newspapers featured glowing articles about Allensworth. Colonel Allensworth had bigger plans to establish a Tuskegee Institute of the West nearby, but state legislators opposed it.

Some believe that the town’s success stirred up jealousy and resentment that led to its demise. “There was a cabal that convened either legally or illegally to strip Allensworth of the things it needed to survive,” says Andrew Schwartz, director of sustainability and global affairs at The Center for Earth Ethics.

Allensworth’s growth was stopped by three devastating setbacks. In 1913, the entire valley experienced a severe drought, and the Pacific Farming Company, which had sold the property didn’t come through with needed water as promised. The town’s wells ran dry, the levels of naturally occurring arsenic rose as the water table dropped, and they couldn’t get water from the nearby river.

In 1914, Santa Fe Pacific Railroad officials decided to bypass Allensworth, and send trains to a white town called Alpaugh about seven miles away. And later that year, the Colonel was hit by a motorcycle and killed in Monrovia while he was on his way to preach in Los Angeles. He was 72. According to some reports, the street was empty of other traffic, causing some to wonder whether Allensworth was targeted intentionally.

Town leaders carried on without him, but it was never the same without their charismatic leader. By the 1920s, the water shortage became extreme, putting farmers out of business. Others, including co-founder Oscar Overr, moved away to work in shipyards and factories supporting the World War I effort.

There’s still a town of Allensworth, with mostly Latinx residents, and a handful of older Black neighbors. The community is ringed by lushly watered almond groves, and many residents labor in California’s $5.6 billion almond industry.

When he visited several years ago, Schwartz says he was shocked at the conditions he saw. “Honestly, it’s like a blown out war zone,” says Schwartz. “They have no access to … clean water. They can’t drink it, they can’t bathe in it.”

The Allensworth Hamlet Plan, adopted by the Tulare County Resource Management Agency in 2017, noted that the area had arsenic-contaminated water, pothole-ridden roads, and no natural gas service, no sewer system or Internet service. Today, Michael Washum, assistant director of the agency, says“we’re always working on trying to improve things” as funding allows.

Valeria Contreras, general manager for the Allensworth Community Service District, confirmed that things are getting better, though the town streets are still in bad shape. Clean water is coming from new chlorinated wells outside of town, grants paid for sidewalks near the schools, and there’s a sewer project in the works. Internet access is expensive, but it’s available.

Though Allensworth’s demographics have shifted, Biscoe says its legacy inspires people who want to live without feeling oppressed. Biscoe sees Colonel Allensworth as a visionary just like Martin Luther King Jr.

“In spite of all that was happening during that time, he was one of those people who stood up and said, “Enough is enough. I have to do something,” says Biscoe.

This story is part of a series on historically significant Black neighborhoods in the U.S.

Follow House Beautiful on Instagram.

Maria C. Hunt is a journalist based in Oakland, where she writes about design, food, wine, and wellness. Follow her on instagram @thebubblygirl.

You Might Also Like