After Building the Atomic Bomb, the Government Dumped Deadly Toxic Waste in a Quiet Suburb

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

I. FIRE

It’s alive.

That’s how the neighbors alongside the landfill describe it: as a living creature, a growling menace—the modern-day incarnation of Typhon, the monster of Greek mythology with a hundred dragon heads, cast into the underworld but still capable of unleashing volcanic powers. It has resided 240 feet down in the Missouri earth, gurgling and hissing, for the past 13 years.

Republic Services, the Phoenix-based owners of the Bridgeton Landfill, where the beast resides, never uses the word fire. Company officials refer to it as a “subsurface smoldering event” or an “underground exothermic heat-generation reaction.” Surrounded by a chain-link fence topped with barbed wire, the smoldering mass gorges on old drywall and broken shingles discarded by construction crews decades ago, opening fissures and tunnels of ash. Sometimes those underground shafts collapse, causing the ground to settle on top of the void, to sink like a punctured air mattress, so that what was once a small mountain is now a lumpy pancake of a 52-acre field.

The gurgling sound is from the vacuuming away of liquids the fire creates. Kevin Stuhlman, assistant fire chief of the Pattonville Fire Protection District, calls it “the nastiest water runoff you could possibly have.” The hissing is the sound of methane and other gases being sucked out to flares, where they’re burned off. Gas extraction wells poke up at regular intervals, making the site look like a tormented voodoo doll from high above. Much of the area is covered with a massive green tarp—a fireproof, three-layer geo-membrane liner that holds in the gases and chokes off the beast’s oxygen supply.

Republic Services crews monitor the fire around the clock, like stockbrokers sweating margins on a volatile trading day: watching ground temperatures, the state of the gases and liquids, the rate at which the ground is sinking. (Republic Services did not respond to multiple requests for comment.) This data is critical because the beast must be contained. If it spreads even a couple hundred yards, it could reach another landfill, West Lake, that is home to a different kind of nightmare. West Lake harbors the origins of the Manhattan Project—47,000 tons of radioactive waste that was, according to an investigation by the Associated Press, MuckRock, and the Missouri Independent, dumped illegally.

Stuhlman grew up nearby and played in Coldwater Creek, the neighborhood hub of outdoor activity, which snaked through his backyard. He became a firefighter 20 years ago to help keep the community safe, but only after he took the job did he learn about the atomic bomb contamination. For two-thirds of his tenure, he has contended with the possibility that those twin menaces could collide—say, if the ground cracks open and fire plumes up, carrying radionuclides into the air currents above a metropolitan area of 2.8 million people.

What happens if that fire reaches that radioactive waste? “No one knows,” Stuhlman says. “It’s never happened.”

II. WAR

On April 17, 1942, Edward Mallinckrodt Jr. sat down for lunch with a longtime friend, the esteemed physicist Arthur Holly Compton, at the Noonday Club in downtown St. Louis. These were rarefied dining quarters, but in terms of the future of humanity, no power lunch was quite like this one.

The nation had entered World War II four months earlier, and reports were trickling in that Hitler’s researchers were two years ahead of the United States in the quest to develop the “ultimate weapon.” Working on behalf of the government, Compton asked Mallinckrodt, chairman of the board of Mallinckrodt Chemical Works, a local company, to take on a daunting task: extract 40 tons of purified uranium from ore freshly mined in the Belgian Congo to fuel the world’s first controlled, self-sustaining nuclear reaction. Three other firms had deemed the untested process too dangerous. But now the stakes were unambiguously high: beating Nazi Germany to the atomic bomb.

Mallinckrodt quickly mobilized his company, and crews working around the clock were soon producing a ton of pure uranium daily. The eventual outcome of the Manhattan Project—the fateful flight of the Enola Gay—is forever etched in history; its ties to St. Louis, however, are lesser known.

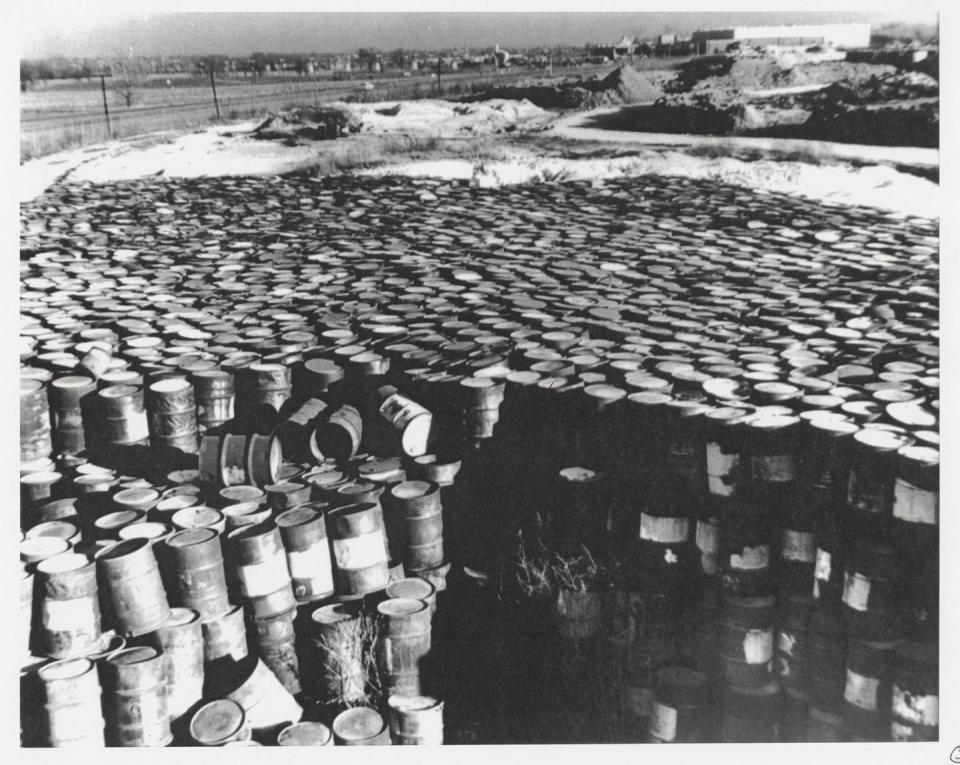

Nuclear power and weaponry remained an important innovation beyond the war’s end, and Mallinckrodt Chemical continued to enrich uranium until 1957. But officials were disinterested in the radioactive waste that the process created. In 1946, the government acquired a property of nearly 22 acres alongside Lambert–St. Louis Municipal Airport, where they shipped barrels of toxic materials.

The northern reaches of St. Louis County were largely unpopulated then, consisting mostly of gently rolling farmland. The communities that were there, however, were not informed of the contents of the thousands of barrels moved to the site, and those who noticed trucks making mysterious deliveries were lied to. In 1946, the St. Louis Star-Times reported that the site had been “used secretly for several months for storage of ‘certain residue materials from the refining of uranium ores’” at Mallinckrodt. Factory officials claimed they were “not radio-active and not dangerous.” The mayor of nearby Berkeley told the newspaper: “If they say the material is not dangerous, we have to take their word for it.”

Although the science about the dangers of uranium was still emerging, the high stakes for public health were already apparent. In 1947, an Atomic Energy Commission panel reported that the uranium byproducts could pose “the gravest of problems” if they were thoughtlessly discarded in gradually disintegrating barrels. In the 1960s, AEC researchers found that the 121,050 tons of radioactive material near the airport contained the largest concentration of thorium-230 in the nation, and possibly the world. One scientist determined that the waste’s thorium concentration was 25,000 times greater than what would exist in nature. Thorium-230 was known to be a health hazard on par with plutonium, and with a half-life of more than 77,000 years, it would decay to radium-226 and grow “hotter”—more radioactive, and more dangerous.

As these barrels sat out in the open, developers began building homes throughout the surrounding area. The combined population in the towns of Florissant, Hazelwood, and Black Jack grew from about 4,000 in the 1950s to around 85,000 today. Virtually no one filling these suburban enclaves had any clue what the government had left behind.

Over time, officials overseeing the Mallinckrodt waste transfer discontinued the use of the barrels and the mirage of safety they implied. Crews heaped the radioactive material into piles that morphed the site into a moonscape, a third of which sat in a floodplain. Wind scattered dried-out uranium byproduct, and runoff from rainstorms washed “directly into the groundwater system,” the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) noted. The terrain also tilted toward Coldwater Creek, which winds northward to the Missouri River. Rainwater that cascaded down the mounds of radioactive waste flowed directly into the stream.

III. PARADISE

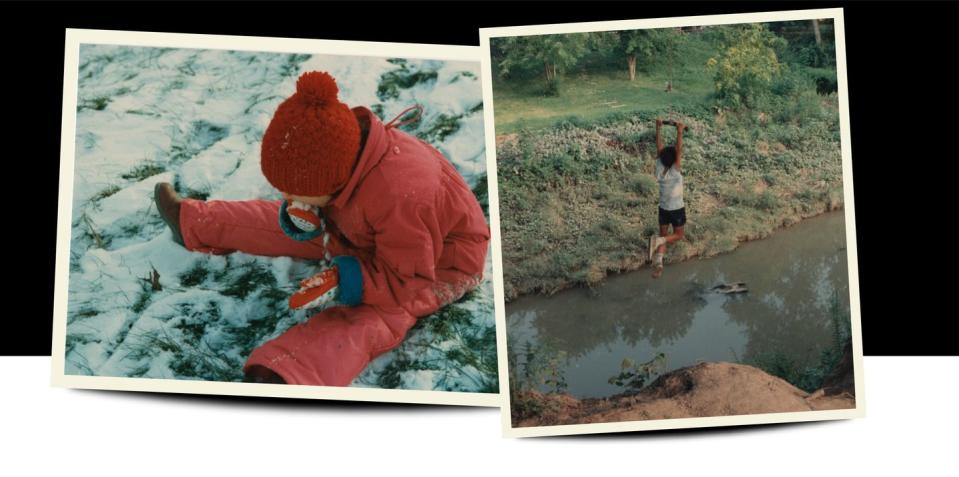

The kids were always outside. That was one treasured part of growing up in Florissant in the 1960s and ’70s: There were the parks and the woods and, especially, Coldwater Creek, which cleaved the landscape like a scalpel, slicing open a paradise for making mud pies, hunting for crawdads, and skipping rocks. As soon as it was warm enough, and often long before and after, neighborhood children were running barefoot and catapulting into the creek from rope swings.

Kim Visintine was one of those kids. Born in 1969, she grew up one of seven; her father owned two amusement parks. Summers were endless and golden. She went off to college—because you had to—and earned an engineering degree before moving back home. “Florissant,” she says, “is a place where some of us have pretty strong roots.”

It took a job at DaimlerChrysler to finally lure Visintine away for good, to Michigan, but in certain ways she’s never truly been able to leave. In 2000, her first child, Zach, was born with a brain tumor so rare that doctors told her there were only 50 documented cases recorded in medical journals. He underwent diagnostic neurosurgery a week after birth and started chemotherapy two weeks later. He died at age 6.

She didn’t connect this tragedy with her childhood home until the 2010s, when a McCluer North High School friend started a Facebook page and made Visintine an administrator, along with a mutual friend, Jenell Wright. Soon dozens of classmates joined. After the usual hellos and how-you-beens, they noticed that almost everyone was grappling with illness.

Scott McClurg had a brain tumor. One of Wright’s best friends was diagnosed with terminal uterine cancer. Another friend had appendix cancer, which was, like Zach’s disease, exceptionally rare. Diane Schanzenbach had two ill family members. And so on. “All of us were sick,” Visintine says, “or our friends were sick, but we had no idea why.”

One common thread: Most everyone had lived along or around Coldwater Creek. As they compared notes, Schanzenbach, a Princeton-educated economist who was teaching at Northwestern at the time, pulled out a grade school yearbook and began checking off names, the statistician in her taking over. She created an online survey that the group distributed to everyone they could find from their old neighborhood, asking for dates, proximity to the creek, and illnesses.

She concluded that it was statistically impossible for the number of cancer cases to be random.

No one in the group knew anything about Mallinckrodt or the radioactive waste. “We had no idea of the creek,” Visintine says. She and many others refer to it as the area’s “dirty little secret.”

In 2011, someone in the group stumbled upon the USACE website for what’s called the Formerly Utilized Sites Remedial Action Program—a government program with an impenetrable name that was created to deal with atomic-waste nightmares. The group learned that remedial work was being done on radioactive waste in the area. “I knew there was a connection the moment we started reading about the thorium-230, uranium-235, and radium-226,” Wright says. Their paradise had been ruined, and now it was on them to do something about it.

IV. FEATHERS

To understand what happened in North St. Louis County—and what’s still happening when Coldwater Creek floods—imagine shaking out the contents of a feather pillow on a windy day. Those feathers will blow away, then land and pick up again in later gusts. Some will float along currents, settling downstream and spreading via floodwaters into the surrounding landscape.

In March 1962, the Atomic Energy Commission, seeking to rid itself of its radioactive-waste problem, offered for sale the 121,050 tons of “uranium-thorium source materials” stashed next to the airport. In 1965, a task force studying the issue recommended removing the waste and closing the site, but the AEC reached a deal with Contemporary Metals, a firm that planned to extract valuable materials, such as copper and nickel, from the residues. The company paid about $1 a ton.

In 1966, a Contemporary Metals subsidiary, Continental Mining and Milling Co., began moving the waste a half mile away to a building in Hazelwood, spilling material from trucks en route. The company went bankrupt soon after, and its lender tried and failed to auction off the residues. In 1969, the creditor sold it to the Cotter Corporation, which planned to ship the waste by rail to its uranium plant in Cañon City, Colorado. Cotter officials calculated that they could reduce shipping costs by drying the material, so they left it outside, again uncovered and exposed to the elements.

Meanwhile, Cotter used an inorganic compound called barium sulfate to recover leftover uranium from the Mallinckrodt residue. After shipping what they could extract to Colorado, Cotter officials were sitting on about 8,700 tons of barium sulfate contaminated with the several tons of uranium that remained.

To offload this slag heap of atomic dross, Cotter mixed it with about 39,000 tons of topsoil—essentially concealing the radioactive material by diluting it with dirt. In 1973, Cotter trucked the toxic residues to the West Lake Landfill in nearby Bridgeton, where various industries had been disposing of municipal solid waste and construction debris since the 1950s. Some of the Cotter waste was used to cover the landfill’s trash.

The AEC knew Cotter’s uranium residue was too radioactive to meet its standards for conventional disposal. The company was clearly in violation of rules prohibiting it from diluting the waste in topsoil to avoid disposing of it safely and legally, according to Nuked: Echoes of the Hiroshima Bomb in St. Louis, by Linda C. Morice. But the AEC was under the false impression that the nuclear waste was buried under 100 feet of municipal waste, and took no action.

In 1974, Congress replaced the AEC with two agencies, one of which—the Nuclear Regulatory Commission—was tasked with overseeing civilian uses of atomic energy. The NRC’s very reason for existence was to make sure companies like Cotter safely handled dangerous radioactive materials. Instead it cut Cotter loose, terminating its license to possess the waste—in all, 47,000 tons of soil laced with radioactive material—and returning the toxic mess to the government’s purview.

By the 1970s, the dangers lurking on the site were obvious, Bob Criss, PhD, a now-retired geologist and geochemist at Washington University in St. Louis, wrote in a searing 2013 report about the West Lake scandal.

The uranium, processed multiple times, had been reduced to tiny particles that permeated the region. “Even one of these microscopic particles is a consequential dose,” says Marco Kaltofen, PhD, a civil engineer and the owner of Boston Chemical Data Corp. He has conducted academic studies connected to the area’s Manhattan Project legacy, including West Lake Landfill, dating back to 2014.

Greater proximity to the nuclear waste site means greater exposure to these particles is likely, Kaltofen says. “There’s our problem. You have unseeable, microscopic particles, of which there are countless trillions and trillions that have gone into the environment.”

V. SURVEILLANCE

“We might get harassed by security again, Karen,” Dawn Chapman calls out from the driver’s seat of her SUV.

“They like to follow us,” Karen Nickel replies from behind her. She is referring to Republic Services, which closely monitors, via various remote cameras, the Bridgeton and West Lake landfills.

We are idling next to Bridgeton Landfill, the headliner of our tour of area waste sites. “This is the back lot that we can get on,” Chapman says as she pulls away. “We’re not supposed to, but we’re gonna try. We’re just gonna say, ‘Hey, we’re lost.’” This draws a round of laughter, the idea that this group of women mistakenly wound up here.

“I am not Dawn Chapman,” Dawn Chapman says, anticipating how she’ll answer questions from security personnel. “Yes, that is Karen Nickel.” More laughter.

As the founders of Just Moms STL, the two women are unlikely to go unrecognized. Since 2013 they have devoted themselves full-time to the task of shaming, cajoling, and browbeating the government into removing the radioactive waste, with a particular emphasis on West Lake. Christen Commuso, who joined forces with them a few years later, is in the back seat next to Nickel.

For Chapman, the surreal journey to this point—to parking alongside a dump on a frigid January day—began with a ferocious stench. She and her family and neighbors were overwhelmed by a rotten-egg, moldy garbage smell that at first was hard to place: An asphalt plant, a compost center, and a methane supplier are all neighborhood fixtures. All she knew was that her kids were getting bloody noses, headaches, and red, teary eyes. Neighbors kept their children indoors even as summer rolled around, limiting their swimming pool time and packing eye drops, inhalers, and masks to the park.

Frustrated and baffled, Chapman called the city, which referred her to the Missouri Department of Natural Resources. That led to a two-hour conversation that left her astonished. She learned that in December 2010, officials at Republic Services had notified authorities of a “subsurface smoldering event” at Bridgeton.

Landfills naturally release leachate and gases as the waste decays, but the fire had drastically accelerated that process—in a location, Chapman learned, that was next to another dump filled with radioactive waste.

She would soon connect with Nickel, who was 10 years old when her family moved to Hazelwood in 1973, a town adjacent to Florissant along Coldwater Creek. One of her passions was softball. The only downside to playing, at least as it pertained to her, was the frequency with which games were flooded out: In spring and summer, Coldwater Creek regularly jumped its banks, especially after the sewer district built stormwater lines that emptied into it. After heavy rains, the stream looked fit for whitewater rafting, and it swamped the adjoining neighborhoods every year—including 64-acre St. Ferdinand Park, home to eight ballfields.

In 2000, Nickel was diagnosed with lupus, an autoimmune disorder that causes inflammation and pain. She began hunting for an explanation and eventually learned that she was part of what St. Louis Magazine, in a story about the radioactive material left behind by Mallinckrodt, described as “a human horror show spanning three quarters of a century.”

Now a grandmother of seven, Nickel shivers at the edge of St. Ferdinand. It’s a January day encased in a sheen of freezing rain, and she points out the ballfields’ proximity to the creek. Yellow caution signs that warn of radioactive material weren’t there when she was a kid. “I’m pretty sure I played ball on every contaminated field,” Nickel says.

Since becoming activists, the women estimate that they’ve worked full-time on the issue for a decade. Their Facebook pages have attracted more than 48,000 followers. They organized one listening session with the Environmental Protection Agency, which has been tasked with the West Lake cleanup, to which almost 1,000 people showed up.

Their involvement has ramped up in direct proportion to concerns over the Bridgeton fire. By 2014, it had crept within 1,000 feet of the radioactive waste, and Bob Criss’s report for the Missouri Coalition for the Environment revealed that West Lake had none of the standard requirements for modern landfills: no basal clay liner, no plastic sheeting, no internal cells, no leachate collection system, no protective cap. He reported that “all available data show that radionuclides are actively migrating in groundwater.” An EPA analysis released that year found that the fire could react with radioactive substances, causing an explosion or the release of radon and other toxic substances.

For all these reasons and more, the three women are a relentless public presence for government officials and Republic Services. During previous forays to the landfills, they were conspicuously followed by a car with what looked like government plates. “It’s intimidation,” Chapman says, “but we’re not doing anything, and they can come and talk to us if they want.”

She is feisty and prone to outrage and profanity. Commuso has a sunnier disposition, tending to smile wryly at cruel twists of irony, whereas Nickel resorts to grimaces and eye rolls. Back at the Bridgeton Landfill, we walk to the chain link fencing surrounding the site. It “used to be a giant mountain,” Chapman says. “I cannot believe how far in a month that’s collapsed. That’s scaring the shit out of me.”

It’s freezing, and we hustle back to the vehicle. “This is gonna make me go home and stress-eat,” she says.

Within a couple of hours, Chapman’s phone buzzes. The caller ID shows it’s from the public affairs office at Republic Services. “They saw us on the monitors at the landfill,” she explains. “No, I’m not gonna answer.”

Later she texts a simple reply: “Fill in your damn hole.”

VI. TRIANGLES

Ashley Bernaugh had only lived in north St. Louis County for two years when she attended her first Army Corps of Engineers meeting about Coldwater Creek’s radioactive waste problem, in 2015. It was a neighborly gesture; she expected to do nothing more than learn what was happening and show support.

Before the event started, she scanned a map of the area. Tracing the creek’s sinewy curves, her eye passed right by her son’s school, Jana Elementary, in Florissant. The map offered no indication that the property was contaminated, although it sits in the creek’s floodplain.

Once the meeting began, she stood to ask the question anyway: Had the school been tested for radioactive material? As Bernaugh recalls it, the Army Corps had an odd answer: Jana wasn’t contaminated because they hadn’t tested it. “If you’re looking for a ‘there’s your sign’ kind of moment,” she says, “that was it.”

Then one day in 2018, after she had become PTA president, she was sitting in her car waiting to pick up her son from school. She watched an official-looking white pickup truck drive through the parking lot, onto the playground, and toward the creek. The people who emerged appeared to be taking samples. Curious about the results, she filed a Freedom of Information Act request. The Army Corps responded that fulfilling it would cost at least $800, which neither she nor the PTA had to spend. Instead, she acted on her growing concerns about the situation by going back to school: Over the next few years she earned a master’s degree in social responsibility and sustainable communities, followed by a second one in public administration.

In the meantime, COVID-19 descended and meetings with the Army Corps were stopped. When they resumed online in November 2021, she inquired again about testing; this time, the Army Corps said the data was only available to the property owner. She replied that they were in luck, because she was in fact a property owner—all local taxpayers were, Jana being a public school.

After she filed another FOIA request, the agency finally furnished a map showing testing locations marked by clusters of red triangles. She stared at them, uncertain what she was looking at, but fearful. Please, she thought, make me wrong.

Unbeknownst to Bernaugh, Christen Commuso at the Missouri Coalition for the Environment had heard her request during the meeting and filed her own FOIA letter. Commuso received a different map, with fewer hot spots marked but actual sample data included. The two women met in May 2022 and began to work together to unpack the information. Eventually they confirmed Bernaugh’s fears: Elevated levels of radon, thorium, and uranium in 38 percent of the 400-plus samples the Army Corps had taken along the creek. The agency acknowledged that its testing had indicated low-level radioactive contamination bordering the school property, but it asserted that the material “did not pose an immediate risk to human health or the environment because the contamination was below ground surface.”

When Bernaugh presented the information to the PTA, many residents and school alumni were stunned. Uncertain what to do next, the Hazelwood School District decided it would permit collection of samples on school grounds by an independent party: Marco Kaltofen of Boston Chemical Data Corp., who in 2016 had been hired by a law firm representing homeowners and residents along Coldwater Creek to periodically harvest samples in the area.

Kaltofen took 32 samples at Jana in August 2022. His data revealed that the kindergarten playground, which had been flooded by Coldwater Creek, contained 48 picocuries per liter of lead-210, a byproduct of uranium’s decay, which is about 22 times above the expected level. (Picocuries are tiny units of measure of the radioactivity concentration in matter.)

The area also had high levels of radium and thorium microparticles. “It’s a high-impact spot because, clearly, Mallinckrodt waste got washed into that location,” Kaltofen says.

In October 2022, the Hazelwood School District announced that it would shutter Jana Elementary indefinitely. And that’s when things got weird.

VII. ANXIETY

Imagine for a moment that you live along Coldwater Creek, or near West Lake. Maybe your kids go to the schools. Maybe you moved in a decade ago and no one mentioned any of this, or maybe you’re a fourth-generation resident who’s seen and heard everything and you still don’t know what to believe. Maybe you’re worried about the fire reaching the radioactive waste, but you don’t have the time to assess the odds of this happening. Or you don’t know to read the EPA’s Section 3.2 of the Responsiveness Summary attached to the 2018 Operable Unit 1 Record of Decision Amendment.

Quite possibly, you have no idea what that even means.

It feels like it all happened forever ago, because it did. But it also feels like things are still happening now, because they probably always will be.

If you were paying attention to the news in 2015, you learned that St. Louis County had quietly posted on its website a shelter-in-place and evacuation plan. Maybe you were among residents who were frightened when you read that the plan’s purpose was to “save lives in the event of a catastrophe” at the landfill. It noted that if the fire reaches the atomic waste, “there is a potential for radioactive fallout to be released in the smoke plume and spread throughout the region.”

Depending on where you lived, you could face either mandatory evacuation or—if you were particularly close to the landfill—be ordered to stay inside, seal your doors and windows. “This event,” the document says, “will most likely occur with little or no warning.”

The plan is still in effect today.

Imagine now that you are Matthew Boenker, whose family owned the farm next to the landfills for five generations. You dreamed of starting a vineyard, but Republic Services wanted your family’s property. The company must prevent the Bridgeton Landfill from sagging too far; if the site goes concave, it could compromise the gas lines and other critical infrastructure and render it inaccessible to rescue vehicles. They wanted your hilltop homestead for the dirt, to bulldoze it all onto the landfill. You moved away; you couldn’t watch them finish the job. “I think we all lost, and it wasn’t just me,” you say. “The whole community lost.”

Or imagine that you’re Phil Moser, program manager of the USACE contingent doing the Coldwater Creek cleanup work. The Corps was a latecomer, sent in by Congress in 1997 to find and remove radioactive material from the stream and adjoining landscape where the radionuclides had spread. You are there to do a job that’s clearly defined in what’s called a “record of decision” that was published in 2005. This was agreed to by the Department of Energy, your boss on this project. You’re just following orders.

But people are scared, and based on conflicting reports about your efforts, some accuse you of being uncaring and negligent and crowd into public meetings to berate you. Like Dawn Chapman: “You made this shit, put it in our community, didn’t clean it up, let it get out, still aren’t really cleaning it up.”

Explaining scientific nuances to a riled-up public is not your forte, but the DOE steadfastly refuses to comment, just leaves you twisting out there.

Finally, imagine you are Terry Briggs, Bridgeton’s mayor. You were elected in 2015, and your job is to deal with voters on one side and countless agencies on the other: the EPA, the DOE, the state government, the county. You try to be diplomatic, but until a few months ago, the DOE refused to even have a conversation.

You’re tired of the affable obliviousness of career government people from D.C. and everywhere else who don’t see this as their problem. You release a letter in 2022 with a member of Congress saying, “We’ve pounded our fists on tables in frustration, demanded answers and accountability… (but) the cleanup of the site is yet to begin.”

You try to help, but no one agrees on what that even means. Some voters urge you to stand pat—no one in their family has gotten sick, so leave the landfill alone. Others are terrified, because they hear rumors and are worried that the water is contaminated, or that radionuclides have worked their way into their house.

You worry about the radioactive material in the groundwater every time it rains. “It’s been studied to death, almost,” you say—yet the risk is still hard to quantify. There’s no budget for an atomic scientist on staff.

You ran for office to solve problems, but this one will almost certainly outlast you. You describe the debacle as “confusing and frustrating. Because there’s always that element of, What’s really happening? And who do I believe?”

All you know for sure is that you may never know.

VIII. MAPS

Once Kim Visintine’s circle of friends zeroed in on the Mallinckrodt contamination, the ailments they had puzzled over suddenly made sense.

They formed a Facebook group called “Coldwater Creek—Just the Facts Please,” and harnessed their various professional skills to collect a massive data set overlaid onto a map showing cancer cases clustered along the river. Their research revealed an “almost dead-on match” for illnesses that can result from long-term exposure to low-level radioactive material, Visintine says. Appendix cancer? Odds of coming down with it are one in 200,000; Visintine’s group logged more than 60 cases in a five-mile radius within their age group.

In 2013, a Missouri Department of Health and Human Services study found no evidence of health problems arising from the radioactive material. Diane Schanzenbach and Jenell Wright, a CPA, pointed out that DHHS’s survey failed to account for people exposed to radiation in Coldwater Creek decades ago who eventually moved. And low-level ionizing radiation takes repeated exposure over years to pose a cancer risk. “So you’re missing all this data because you’re pulling just from census data—because that’s how epidemiology studies are created,” Visintine says. “Very flawed.”

When the group presented its findings, the agency agreed to reexamine cancer cases in eight zip codes, from 1996 until 2011. A year later, the DHHS released a new report showing that compared with rates in the rest of the state, the number of leukemia cases was “statistically significantly higher,” as was the number of colon, prostate, kidney, bladder, and female breast cancer cases. In one zip code, the number of cases of brain and other nervous-system cancers among children 17 and younger was significantly higher. “Scientific studies have authoritatively linked ionizing radiation exposure to the development of some types of cancer, particularly leukemia,” the report states.

For three years, the group also held monthly conference calls with the federal DHHS’s Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, which concluded in 2019 that radiological contamination in Coldwater Creek “could have increased the risk of some types of cancer”—including lung cancer, bone cancer, and leukemia—for “people who played or lived there.”

The Just the Facts group also shared its cancer map and data with the Army Corps of Engineers in a bid to convince the agency to expand its search for radioactive material beyond the creek bed to areas historically prone to flooding. Eventually, Visintine says, the Corps acknowledged to her group that the contamination went beyond what was originally known. Visintine describes it as “one of the most profound, really positive things that our group has done.”

For some, though, these accomplishments came years too late. As the parents of a baby girl, Mary and Gerard Oscko were happy to find a home on leafy Alma Drive in Hazelwood in the mid-1980s. They had both grown up in the area, and the house bordered St. Cin Park, a 10-acre green space with horseshoe pits, playgrounds, and a walking path that mirrors Coldwater Creek’s undulations. There was only one apparent downside: The creek flooded almost annually, swamping the park, filling neighbors’ basements, and creating the impression that the Osckos—whose home was just high enough to stay dry—owned lakefront property.

Mary walked on the park’s trail every day. As the kids grew, she decided to return to school to become a nurse. She’d nearly graduated when she started experiencing severe back pain. On Thanksgiving 2013, she was in such agony that they chased the turkey and stuffing with an ER visit. X-rays and scans revealed nothing, and a doctor sent her home with pain meds. Two days later, she was back. “That’s when they found the spots,” Gerard says, “and then it was confirmed through a biopsy.” Mary had terminal stage 4 lung cancer.

After they processed the devastating news, the Osckos grew curious. Mary had never smoked, nor did any family members, and only after they began investigating potential causes did they discover the area’s history. “We knew what the Manhattan Project was,” Gerard says. “But we realized there was waste product all over North County because of it.”

As Mary began treatments, she learned from the Just the Facts group that hundreds of her neighbors had come down with similar illnesses. Around the corner, in fact, on neighboring Palm Drive alone, there were more than 20 cancer cases.

IX. PIANO

In college, Dawn Chapman studied music education and performance, with a focus on piano and violin. Her goal was to teach music to children with special needs. She took time off to raise a family and help her husband through a protracted illness, but she was about to enroll in the nine course hours she still needed to graduate when she learned of the radioactive waste. The quest for facts became so all-consuming that her piano fell out of tune. “I’m like, ‘Oh my god, I gotta call a tuner’—and then I was like, ‘What’s the point?” she says. “Because I didn’t even get out Christmas music last year.”

We’re sitting in Karen Nickel’s kitchen. In the adjoining living room, Nickel’s husband is playing with their grandson. She recalls a time several years ago when Chapman announced that she was starting a job. “I’m like, ‘No you’re not,’” Nickel says, laughing. “I’m gonna call and tell them you can’t come.” Chapman worked for two weeks before apologetically quitting.

Chapman and Nickel have surrendered 40 hours a week to this for more than a decade. Along with a third compatriot, Christen Commuso, they estimate they’ve devoured tens of thousands of pages of dense reports by various government agencies—teaching themselves the science along the way—to know the material as well as the engineers do, so they can pose questions and call out incomplete or misleading responses. The idea, as Chapman puts it, is to “know the answer before we ask.”

The answers mean little if they don’t have the right allies, so they must then solicit the involvement of members of Congress, mayors, environmental groups, and so on.

They’ve starred in an HBO documentary. They’ve been invited to the White House—twice—and the United Nations. They’ve elicited bipartisan letters from members of Congress to federal agencies. Each letter opens a door, brings in new information—“but then guess what?” Chapman says. “Nobody but the three of us go through them.” Each new batch of data and findings is digested and regurgitated for Congress which, inevitably, leads to another letter, more data, more reports. And so on, in a seemingly infinite loop.

Chapman and her husband sold their house—“and I disclosed everything and lost my ass on it”—in part because they needed to lower their expenses for her to continue devoting herself to the cause.

Christen Commuso signed up for a photography class but only made it through two sessions. “I would prefer to be out in nature somewhere, doing stuff,” she says. “I’d probably be a biologist somewhere.” There are so many rabbit holes to plunge down, she feels guilty reading for pleasure.

Have they helped? They believe so. In the past, the DOE or the Army Corps document-dumped, signaled that they’d done their job, moved on. The three women not only read each page, Chapman says, but also “highlight the shit out of it. And we’re gonna find stuff we don’t like.” They believe they have created more accountability.

They hope for a Congressional hearing. But regardless of who else takes up the cause, they will remain vigilant for another decade, two if necessary. “When people let down their guard,” Chapman says, “and community groups kind of say, ‘Okay, we’re done,’ that’s when the monkey business starts.”

X. TIME BOMBS

For millions of Americans, weekly trips to the dump bring a sense of tangible satisfaction. Toss your garbage bags onto the heap, drive off. Chore accomplished, problem solved.

That’s what the Cotter Corporation hoped to do in 1973: Make the refuse go away. That’s largely what the DOE and its predecessors have done for decades: Let it be someone else’s headache.

For those living with the Manhattan Project’s toxic legacy, there is no such easy solution. After nearly two months of virtual learning in autumn 2022, the families of Jana Elementary School learned that students would be split up into five different area schools. Jana was a school of 400 kids, about 80 percent of whom are Black; it served a fair number of economically disadvantaged residents. To make matters more painful, there was—and continues to be—vehement disagreement within the scientific community over the necessity of blowing up a school community.

Oddly, both the Army Corps of Engineers and a private contractor, SCI Engineering, came up with test results that hewed closely to those of Boston Chemical. The disagreement centered around a single question: How harmful are the levels of lead-210 they found?

Kaltofen found hundreds of test samples from the school property—using the same technology as the DOE and EPA—that “are completely identical to Mallinckrodt’s own.” He knows that because in 1955, a company report laid out the contents of its uranium waste using X-ray testing. “You usually don’t get a bullet that has been signed by the gunner,” Kaltofen says. “But essentially, that’s what you have in this location.”

The Army Corps forcefully disputed Kaltofen’s findings, insisting in three reports released during the first half of 2023 that the school grounds and building are “safe from a radiological standpoint.” In short, this doesn’t mean there’s no radioactivity there; it means the levels of radioactivity within the top six inches of soil are not at levels that meet the threshold for a cleanup. Though part of the school property is in a floodplain, the building itself is not and has never flooded, the Corps argued, and thus there could be no radioactive material inside.

The Missouri DHHS reported that there wasn’t enough information to arrive at “meaningful conclusions.” Meanwhile, several local college professors held a public health forum at Saint Louis University to challenge the Boston Chemical findings. Roger Lewis, PhD, a professor emeritus of environmental and occupational health at the university, contends that the lead-210 levels not only pose no health hazard but appeared on the school property naturally, via precipitation. Radioactive substances have a chemical signature—like a fingerprint—that indicates which isotopes are in the material, and the soil and dust samples present in the school findings “did not support the claim that the [radioactive material] was from Mallinckrodt,” he says. “So [Kaltofen] is wrong on both points.”

Furthermore, the International Commission on Radiation Protection and the American Health Physics Society have challenged the notion that microparticles can cause cancer, Lewis says. “What Boston Chemical does is they dismiss the aggregate exposure of all of the particles that might be present in an area,” he says, “and are only interested in that sort of needle in a haystack to try to determine what’s bad.”

The scientists even disagree on whether the creek’s proximity is an issue. The Army Corps contends that to be exposed to radioactivity, schoolchildren would have to wander 200 yards off campus and descend a steep and perilous embankment, then ingest the soil. But Kaltofen responds that shoes are known vectors of radioactive material and could easily bring it into their midst, where it could be inadvertently handled and ingested.

The question of whether the lead-210 is naturally occurring is moot, he says. “The kids’ lung tissue doesn’t care if it was Mallinckrodt’s or Mother Nature’s; the reaction is the same,” Kaltofen says. “It’s much higher than average at that location and would need to be cleaned up even if it were completely natural.”

How are citizens to unravel this Gordian knot of science? Popular Mechanics reached out to the DOE’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory for an independent expert. A spokesperson referred questions to the DOE, where a spokesperson in turn referred them back to the Army Corps—an airtight and impenetrable bureaucratic loop.

Faced with sets of highly complex but contradictory facts, people get frustrated. Would-be allies become divided. Visintine believes the Jana crisis was created by newcomers acting on emotion and lacking adequate historical context or scientific understanding. “When I was a kid in the late 60s and early ’70s,” she says, “the house that Ashley (Bernaugh) lives in was not even built.”

She also believes it’s pointless to attack the Army Corps, which is just the cleanup crew. But the women of Just Moms STL point out that the Corps is their only access point to the otherwise inaccessible Department of Energy.

Consider: The EPA plans to eventually leave the West Lake site up in a pristine, pre-contamination state, while the Army Corps’ orders for Coldwater Creek changed in 2005 to meet a lower standard—one that the Missouri DNR says “may not be safe for long-term exposures.” The EPA and DOE have different cleanup standards; the former removes the waste to pre-contamination levels, while the DOE remediates to a level at which one out of 10,000 people will get terminal cancer. “It’s like, wait a minute: Who the fuck has the right to (decide) that, except for the person that’s accepting the risk?” Chapman says. The Army Corps, she says, is “trying to make people comfortable with living with what’s happened in their community, and that is way beyond what they should be worried about.”

The conflicts and disagreements have only deepened the hurt and confusion, and the fear. Many of those who grew up around Coldwater Creek, Visintine says, are “ticking time bombs. Are we going to end up with cancer, or not?”

XI. TECHNOLOGY

For several years, while the fire in Bridgeton Landfill crept closer to West Lake radioactive refuse, the government moved indecisively. In 2014, the EPA proposed the creation of an isolation barrier—a kind of firebreak—in a slender neck linking West Lake and Bridgeton. The agency would spend several months deciding how to proceed, and then another 14 to 18 months on its design. It never happened. The EPA determined that “such a barrier was not feasible to safely install without creating the chance for a surface fire and may not remain intact and be effective in the longer term,” agency spokesman Kellen Ashford indicated via email. The Just Moms group says the agency was too plodding and missed its chance.

In 2018, the EPA announced that it would remove 70 percent of West Lake’s radioactive waste within four to five years. Then-Secretary Scott Pruitt proposed spending $236 million to partially excavate the site. That never happened either.

The state of Missouri sued Republic Services in 2013, alleging violations of state environmental regulations. This prompted the firm to continue work that was already underway, and which would eventually entail spending approximately $200 million on cutting-edge technology, including building what the company calls a “world-class liquids-pretreatment facility.” The underground leachate system pumps liquids into four one-million-gallon tanks for processing and treatment. Once neutralized, it can flush through the sewer system.

Republic installed odor monitoring and response technology and a massive gas-extraction system. “With their sampling data, and it’s real-time, they can shift where they need to focus,” says Kevin Stuhlman of the Pattonville Fire Protection District.

The firm also invested in an innovative heat-extraction barrier—a set of underground cooling coils designed to keep the fire from the radioactive waste. The system pumps chilled water underground to slow the incineration.

These technologies helped Republic Services settle the lawsuit in 2018 while agreeing to extensive ongoing monitoring of the air and groundwater. Stuhlman says the methane and leachate production has slowed, temperature readings have dropped, and the ground isn’t sinking as quickly, resulting in what Stuhlman calls a “quote-unquote managed state.”

The fire department has updated its equipment to better measure radiation levels and detect radioactive particles to avoid carrying any off the landfill, Stuhlman says. It has emergency plans with contingencies for different scenarios, and then contingencies for those contingencies.

The worst-case scenario, as Stuhlman sees it: The fire reaches the waste and releases a plume of smoke filled with active isotopes—a radioactive cloud, or “dirty bomb.” The emergency plans must factor in such variables as wind speed and direction. “We’re nowhere near that right now, in my opinion,” he says. “Things are better than they were.”

That’s cold comfort for neighbors who worry about extreme weather—drought or a tornado—that could collapse the delicate interior layers of the landfill. “We’re at the mercy of all this experimental technology,” Dawn Chapman says.

The fire may now be within 300 feet of West Lake’s radioactive waste—but that’s a guess, because the Mallinckrodt material has dispersed over time. In March, the EPA reported that two years of sampling had revealed that the landfill’s contaminated areas were “larger than previously known.” This was bitter vindication for Just Moms STL, which had asked for additional testing for years. “It felt like more of a punch in the gut,” Commuso says. “We were basically told we were right, but it never feels good to be right in this situation.”

No one knows how long the fire will burn. Stuhlman is the third assistant chief to deal with the issue. When he retires in four years, a fourth will take over.

Fifty years after the Cotter Corporation dumped the radioactive waste, the EPA is drawing up a blueprint for its removal. Once that’s done, the agency must get the responsible parties to sign an “enforceable agreement to perform the cleanup,” spokesman Ashford says. “The EPA does not currently have an estimate of when that will begin.”

Unsurprisingly, every step the agencies take is trailed by clouds of skepticism. Residents grapple with a maddening paradox: They must beg government entities to do a job that few trust them to actually do. “We told you it was everywhere. You told us it wasn’t,” Commuso says. “How can we trust you to clean this up?”

As for Coldwater Creek? The Army Corps expects the cleanup to take until 2038—and in the meantime, the radiation keeps getting hotter. U.S. Senator Josh Hawley introduced legislation that would provide compensation for victims of the contamination. Attached to the defense spending bill, it passed the Senate in July but still faces legislative hurdles. (His office did not respond to requests for comment.) All of these are hopeful signs, but in the meantime, the struggle continues.

“We won the war,” Dawn Chapman says, “and we’re still out on the battlefield here in St. Louis.”

XII. CONSEQUENCES

Since Kim Visintine started Just the Facts in 2011, the group has chronicled thousands of cancer cases: brain cancer, breast cancer, uterine cancer, leukemia, appendix cancer, and more. “Exposure does not rate a slam dunk for cancer, but it does make you at a higher risk,” she says. So you live in fear.

Thompson Davis, chair of the psychology department at the University of Alabama, says that in itself—that unending, existential anxiety—can take a toll. He’s not involved with the situation in North St. Louis County, but in general, he says, living with “long-term uninterrupted stress” over health issues is thought to contribute to risk factors for high blood pressure, cardiac problems, diminished cognitive abilities, depression, and anxiety disorders. “If it’s a prolonged stressor,” he says, “it just wears you down, and eventually it will impact your immune system, your body, and your mental and physical health.”

Who will ultimately bear the cost for all these lives lost, for families decimated, for careers derailed? Who will pay?

So far, the USACE has spent more than $700 million on Coldwater Creek. That’s taxpayer money. The EPA does not yet have an estimate for West Lake, but it will likely be in the tens or hundreds of millions. The DOE, Republic Services, and Cotter are all named “potentially responsible parties” and may be forced to bear the cost—but again, the DOE is funded by taxpayers, including the people of North St. Louis County.

But who really is to blame? Five different federal agencies have been responsible for the Mallinckrodt atomic waste since 1946, from the Atomic Energy Commission to the DOE. All this agency shuffling and responsibility offloading has resulted in a predictable lack of coherence and accountability that has manifested in two ways. One has been obfuscation. The agencies have been willfully opaque. They “operated in secret, prioritized nuclear production above all else, gave false assurances to the press and public, and hired contractors without closely supervising them,” Morice wrote in Nuked. One AEC official admitted that the waste drew little attention because it “was not glamorous; there were no careers; it was messy.” The investigation by the Associated Press, MuckRock, and the Missouri Independent found that the government didn’t inform the public about the creek’s hazards until 1981, when the EPA listed it among the nation’s most polluted waterways.

The other common thread: an abiding awareness of a slow-motion public health disaster in the making. Knowing the risk connected with the radioactive waste, the federal government, for generations, did nothing. The AEC ignored its own panels of experts in both the 1940s and the 1960s. In 1988, a Nuclear Regulatory Commission study found that the landfill contained dangerous substances that posed major long-term health risks and “will likely require moving the material to a carefully designed and constructed ‘disposal cell.’” But the NRC did nothing, and in 1995 it shifted the purview of West Lake to the EPA’s Superfund program.

Once, as an exercise, Bob Criss, the Washington University geologist and geochemist, created a chart of what material went where, sent by which party, and when. “It’s the biggest mess of spaghetti you ever saw,” he says. “There’s just arrows going every which way.”

What galls him most is the total absence of any consequences. “Where are the indictments?” he says, his voice rising. “Why hasn’t anyone been held to account?”

The saga is an all-time point of reference for the boundlessness of the nation’s ability to wage war but utterly fail at peace.

Criss proposes a thought experiment: Imagine driving down a city street, discarding trash as you go. “Throw a few cans out the window and you’re going to get a big fine,” Criss says. “Well, here’s somebody that dumped 100,000 tons of stuff.”

“They sure make it look like the Keystone Kops,” he says. “They’re just monsters.”

XIII. SILENCE

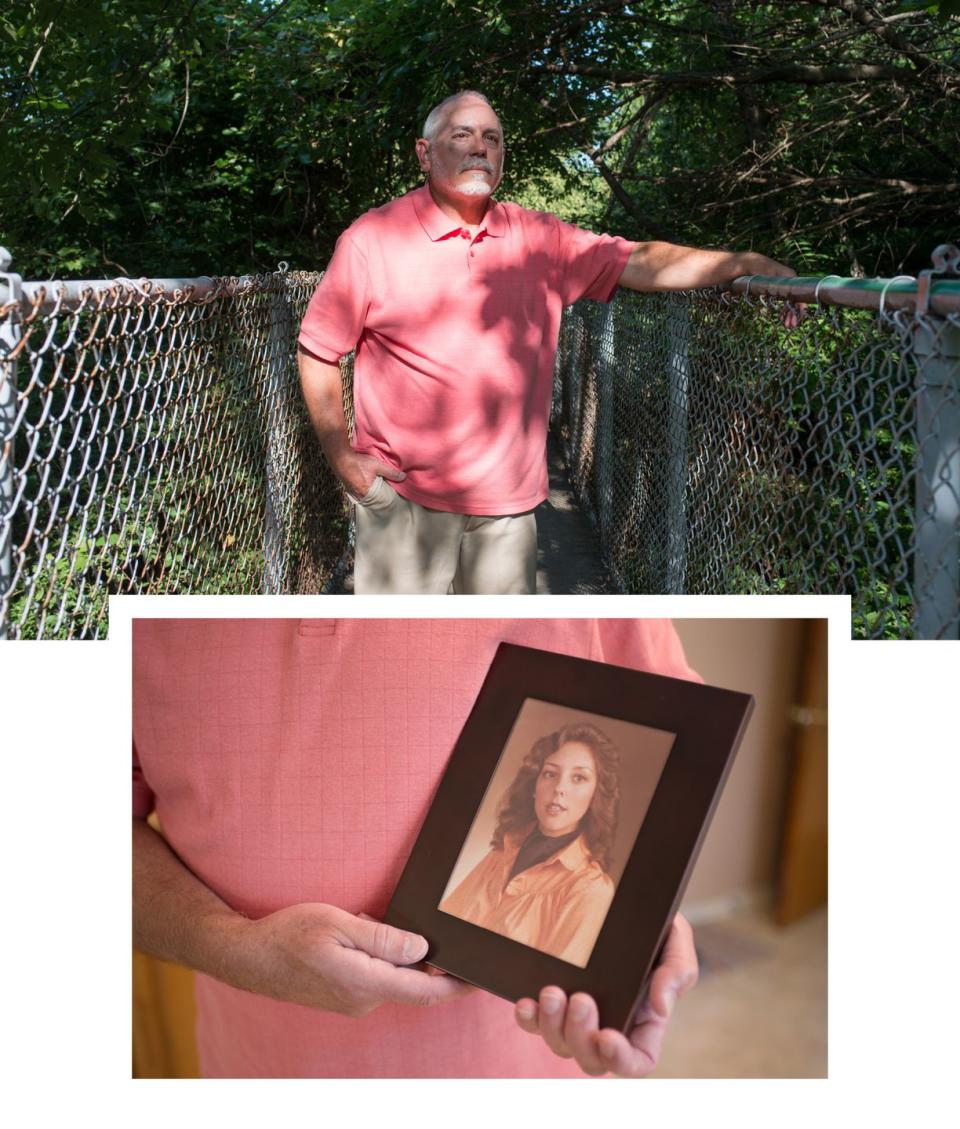

Gerald Oscko knows something about consequences.

As Mary struggled with cancer, the couple learned more than they ever wanted to know about radioactive waste. They learned that when radioactive material spreads, the newly contaminated sites are called “vicinity properties.” From the three original sites—the airport, Latty Avenue, and West Lake—the government has now identified more than 700 vicinity properties. The USACE confirmed in 2015 that St. Cin Park—the park bordering the Osckos’ home—was one of them.

The Osckos also learned there were large quantities of thorium in that Mallinckrodt waste. As it decays, thorium becomes radium, which in turn becomes radon—the nation’s second leading cause of lung cancer. The park was eventually remediated, but in 2016, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention told people to avoid Coldwater Creek entirely.

Instead of pursuing a nursing career, Mary Oscko focused on fighting cancer and helping neighbors avoid a similar fate. She added her voice to those demanding that the government remove the contamination. In one photograph, she’s sitting in St. Cin holding a sign that says, “I’m Dying. Ask Me Why??”

In 2019, doctors found eight spots on her brain—more cancer. With more chemotherapy, she experienced another respite until 2022. That’s when the headaches began. This time the cancer had spread to her brain fluid, which is untreatable. Her final doses of radiation that spring served a singular purpose: to let her live long enough to attend her son’s wedding in May. She died in February 2023, at 63.

When Gerard sees his four grandsons, they avoid the St. Cin playground. He’s 65 years old now and has no plans to move; the house is paid for, and he’s made peace with life by Coldwater Creek.

But the in-between is what gets him. The house feels empty, as if it grew a new wing. The silence sometimes swallows him whole. “It’s just so quiet now because there’s—nobody’s here,” he says, haltingly. “So I’m still trying to get used to all that.”

Maybe this is the hardest it will get. Maybe the community groups will prevail, and Congress will force action. Maybe the government will move quickly to finally—finally, after 80 years—lift away the toxic cloud. Maybe the lowest ebb will be the turn of the tide.

But if you ask neighbors around north St. Louis, they’ll tell you that all they know for sure is this: Generations come and go, life tumbles forward, and people die, often too early. Some wrongs can never be righted, and some holes can never be filled.

You Might Also Like