My Bug-Out Bag, The Wilderness, and Me

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

In late November, on a Tuesday afternoon, my husband locked me out of the house. It was the first real day of snow in northern Wisconsin, gray and cold, and sticky flakes dusted the forest around our home. Not the weather I’d have chosen for a night unsheltered in the woods, but in a way, I reassured myself, that made the experiment realistic: survivors can’t be choosers.

The week before, a package had arrived in the mail from a company called Echo Sigma (motto: “Be ready for anything”) with a backpack, or “bug-out bag,” containing all I needed—supposedly—to survive for three days in an emergency, after “bugging out” of modern life. My mission was to live out of it for twenty-four hours, and to learn something along the way about survival, or at least about the ways that we try to prepare for it. I hadn’t peeked in the bag; I wouldn’t know its contents until I got into the woods. I wore insulated coveralls—I’m not a complete masochist—and brought nothing else with me but a camera and Pepé, my most competent dog. The pack was the size of a high school book bag, which seemed awfully small to hold food, water, shelter, and warmth, but at eighteen pounds, at least it had a comforting heft.

I crossed a broad meadow and entered the trees, where it was instantly colder and darker. Pepé trotted ahead. Already the snow was starting to stick. I found a rock to sit on, took off my pack, and unzipped it, waiting to learn my fate.

72-Hour Emergency Go Bag

$309.99

Echo Sigma

Over the last few years, the demand for at-home survival supplies—the kind your suburban neighbor might keep in their garage—has skyrocketed. “We ten-x’ed our sales during Covid,” Chris Reidel, the co-owner of Echo Sigma, told me. “We went from working in my garage with a couple high-schoolers, who would come and pack bags, to hiring 15 to 20 employees overnight. People were getting so scared. We’d never seen that.”

It got so bad that bug-out bag manufacturers ran out of supplies. Reidel was going to Home Depot every morning at 4:45, trying to buy anything he could the moment they opened. At the time, I watched this market with abstract interest, perusing websites and clicking the occasional pop-up ad. A surprising number of survival kits featured zombies as a selling point, presumably because they get at the human fear of being hunted without invoking the more terrifying realities of, say, war. But I’d never seen a bug-out bag in person until now.

It’s not that I’m a prepper, although up here in the Northwoods, the line between prepared and paranoid can blur. When you lose power for a week at a time, as we have from summer storms, you’d be foolish not to consider a generator and stored water. When I’ve read prepper forums—ostensibly as research for my novel, Small Game, but come on, I chose the topic for a reason—I’ve often seen an even split between the folks who fantasize about guarding their stocks of fish antibiotics, post-apocalypse, from desperate and presumably infected neighbors, and those who remind others that the most likely crises are mundane, like unemployment. The latter recommend paying off debt and getting in shape. The former, stockpiling ammunition.

To be honest, the idea of preparedness has always struck me as solid and reassuring. As a kid in suburban California, I recall having a strong, uneasy sense that most human beings throughout history have dealt with famines, natural disasters, and so on, and that I could hardly presume to live my whole life as the lucky exception. As an adult, I became a long-distance dogsledder, a pursuit that even on its best days toes the line between recreation and survival. In those first weeks of Covid lockdown, when friends were panic-buying toilet paper, my husband and I received identical packages from Amazon: without mentioning it to the other, we had both ordered snares.

Which, come to think of it, wouldn’t be a bad thing to find in the bug-out bag. As I considered the pack, I felt a rush of excitement, like I was opening a long-awaited gift.

The outside of the pack had a flashlight and multitool strapped to it, presumably for easy access, though the flashlight’s batteries were packed much deeper inside. I hate multitools—I find them fiddly, and prefer a fixed-blade knife for just about everything—but I acknowledge that’s a me problem, so I tucked it in my pocket and continued the search.

As it turned out, the main pocket of the pack contained a cardboard box stuffed full with metallic pouches of drinking water. I know water is important and all, blah blah, but I’ll confess a rush of dismay when I opened it—mainly because the water took up so much space that it didn’t leave much room for other gear to make my night more pleasant. Still, resolved to hydrate, I tore the corner of a water packet and drank it. It tasted startlingly horrible, like licking a handful of change.

The smaller pockets contained a mishmash of items, including a first aid kit, goggles, off-brand N95 mask, leather gloves, fire-starters, glow sticks, a spiral-bound book of survival instructions, a foil emergency blanket, and a folded piece of plastic, about the size of a gas station poncho, that was labeled—optimistically, I thought—a “tube tent.”

No food? I searched again, pawing through everything twice more before realizing that the food was, in fact, tucked in with the water packets: a single dense rectangle marked MAYDAY Emergency Rations / Non-Thirst Provoking. Inside was a thick substance, portioned into squares like a graham cracker, that smelled strongly of apples. With 12,000 calories in the package, I could afford 400 per meal over the course of the day. I felt grateful that I wouldn’t be staying out for longer—it meant I could afford to eat a chunk now.

Unfortunately, the food-substance’s pleasant fragrance didn’t extend to taste; it was extremely dry, with a clay-like texture that coated my tongue. Without thinking, I spit my half-chewed bite onto the snow. Pepé ate it, then nosed the package for more, and after giving her another small piece, I tucked the rest in the bag for safekeeping. She could catch rabbits. What could I catch, with my tiny multitool? Pneumonia?

At that point, my prospects for the night were starting to seem grim. I’ve spent countless nights in the woods, often alone, so I knew there was nothing to be afraid of—but I also knew how excruciatingly slowly the hours pass when you’re cold or uncomfortable and don’t have the distraction of a phone. My biggest challenge would be insulating myself from the ground. I had no sleeping pad, and the frozen dirt would suck warmth from my body far faster than the air would. For a few minutes, I considered constructing some sort of campfire and lean-to situation, but I didn’t trust all this plastic around flames, and the last thing I wanted was to test the first-aid kit by treating burns in the dark. It was warm enough that the snowflakes were melting on my shoulders and my shirt was growing damp, so shelter was a top priority. Tube tent it was.

The tube—“tent” feels too generous a word—was a translucent orange garbage bag that opened on both sides, with a thin rope to thread through the middle and tie to trees. The package instructions said to weigh down the sidesends with rocks to keep the tube open. It was easy enough to assemble, but the result did not inspire confidence; there’s a reason people don’t camp with this stuff. It looked like a piece of litter that got caught on its journey to blowing away.

Next step: insulation. If I’d had a fixed-blade or hatchet, I could have cut pine boughs to sleep on, but instead I pulled up masses of dead grass by hand and shook them dry. Pepé followed, nosing for mice in the grass. She froze and leapt when she heard them, and caught two by the time I’d piled a decent layer of bedding under the tube.

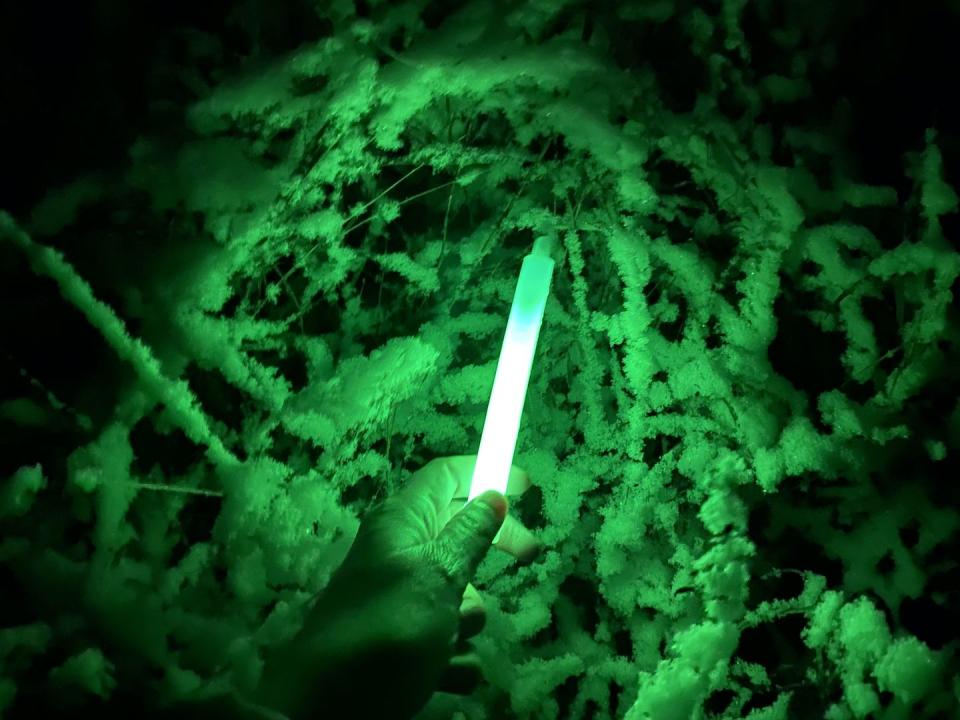

As dusk fell, I crawled inside, calling Pepé after me. It was getting dark early now; the sun wouldn’t rise for almost fifteen hours, and even if I slept for eight—highly unlikely, given the circumstances—I’d have seven more waking hours to wait for dawn. Though I’d been tempted to open the survival instruction book earlier, I’d saved it until now, when I knew I’d need the entertainment (or else a distraction from the cold). I clicked on the flashlight and, on second thought, cracked a glow stick, too, bathing us both in green light.

The book, titled THE WALLACE GUIDEBOOK FOR EMERGENCY CARE AND SURVIVAL, featured 91 pages of detailed instructions. The words were almost blurry, like they were printed from a photocopy of a photocopy, and, mysteriously, many of the periods in the text had disappeared, leaving only small emptinesses behind. The effect, along with some random line breaks, made it seem like a poetry zine or self-conscious project of found text, not least because of sentences like, “The never-ending quest of understanding the problems of accommodating you and I under stress, indeed seems endless.” Tell me about it, baby.

The book’s instructions were arranged by type of emergency, ranging from auto breakdown to injuries to depression, with handy tips sprinkled throughout: “Do not perform any surgical procedures unless it is absolutely necessary (surgeons excepted).” A chapter on curating a survival support team recommended seeking out women with multiple children (“This group will probably be your most reliable one They’ve done it all. They understand physical pain and emotional stress”). One page pronounced, “THE DEAD ARE NOW DEAD! Care for the living!” The book ended, inexplicably, with “Congratulations!!”

It was a fever dream, hunched in the tube with the green light, as snow slid down the plastic around us. But the page I kept flipping back to was the dedication.

For those who have been there, and those who may yet be there.

Those who may yet be there—well. That makes everyone.

I’ll tell you what I’d pack, if I were making a bug-out bag: a tarp, a blanket, sutures, a good knife—but also chocolate, lots of it, and a novel. Something to help you get by, whether you’re sleeping in the woods or on the floor of an airport as you travel to a loved one’s side. In the long hours of that night and the next morning, as I lay curled tight in the rippling plastic tube, I’d find myself wishing for a soft pillow, and a warmer layer to wrap around myself than the bag’s flimsy foil emergency blanket, which tore even as I opened the package. I wanted a guitar to play; I wanted music in the darkness. When the sun finally rose, the black sky turning gray through the trees, I wanted something hot and sweet to drink, or at least to hold steaming in my hands. And when I finally trekked out of the woods, toward home, I wanted clean, dry clothes and soup.

$20.78

amazon.com

But I don’t want to make my own bag; I like that someone packed one for me. There was something to be said for the formality of it all. I kind of wished that—like most customers, surely—I had never opened the bag and had tucked it on the top shelf of my closet, where it would glow behind the sweaters, pristine and pretentious, each time I turned on the light. It seemed that half the project of prepping was bearing witness to the fact that we’re all on the edge of survival, always; it’s a memento mori to our own fragility. Things break, ourselves included; things fall down. It’s not paranoia to acknowledge that the most stable parts of our lives can be stripped away. And when they are, where will we land? Will we land at all?

Prepping, survivalism, whatever you want to call it, is a kind of promise: I don’t know where I’ll land, but I’ll land somewhere. Whatever happens, I’ll find a way to get by.

I didn’t sleep much that night, but I must have drifted off at some point, because I remember waking up to find that Pepé was gone. She had wandered back to the house. People say dogs are loyal, but they’re pretty happy, I’ve learned, to ditch you for comfort, especially when they know that you can find your way home.

You Might Also Like