My Brother Killed Himself 7 Years Ago, and I Still Blame Myself

This past summer, it seemed that every news cycle brought a report of a celebrity suicide, from fashion designer Kate Spade to chef Anthony Bourdain to rapper Mac Miller. But for the people they left behind, the pain is just beginning.

When my brother killed himself, I learned that when someone takes their life, survivors are left not only to cope with the grief and sadness of the death but also to wrestle with the stigma and blame surrounding suicide.

RELATED: 6 Warning Signs of a Mental Illness Everyone Should Know

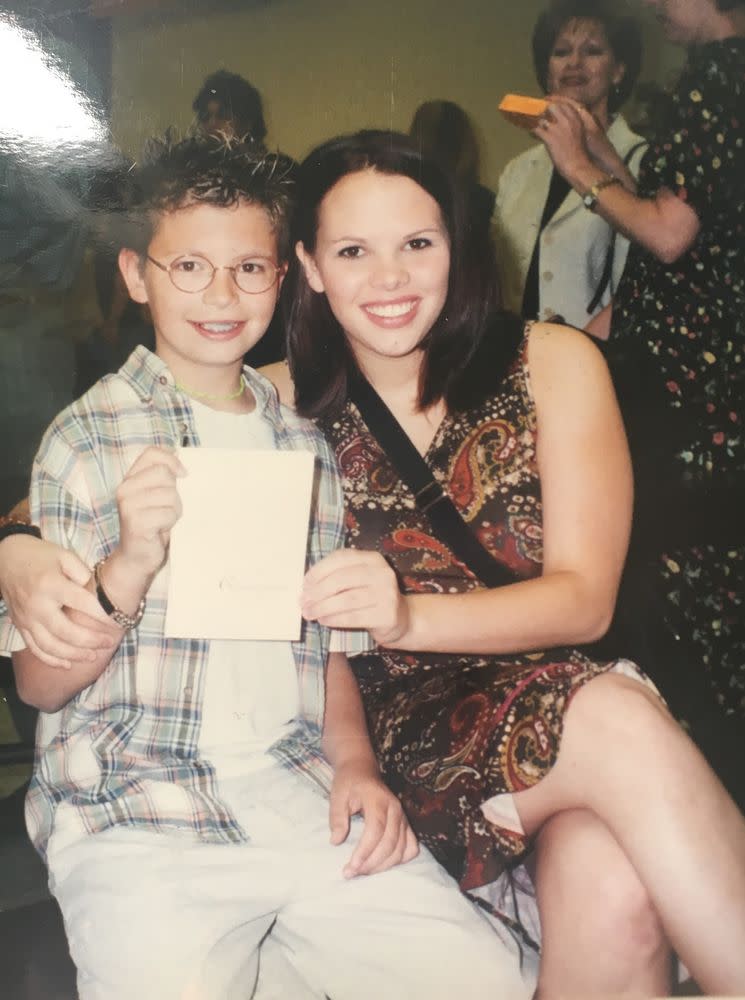

My brother, Jay, was diagnosed with schizophrenia not long after his 19th birthday. Despite multiple hospitalizations, he refused to take medication for his very serious mental illness, which bloomed inside his mind until he was in an acute psychotic state. By age 20, Jay left home and was living on the streets, hitchhiking from town to town, shouting at strangers that the world was coming to an end. At age 21, he ended his life.

Suicide is on the rise in the United States. According to the Center for Disease Control, approximately 45,000 Americans took their lives in 2016, a 60% increase since 1980. People typically do not wake up one day and decide to kill themselves; years of pain and anguish usually precede the decision.

I actually spoke to my brother the day he ended his life. He had been keeping a blog to warn people about the end of days and had just written a particularly worrisome post. He was in Oregon at that time. I called him from my office in New York City as soon as I thought he would be awake. As usual, I asked, “How’s my favorite brother?” and he replied, “I’m your only brother,” but it was evident by his frantic and disorganized speech that he was in panic mode.

I begged him for what felt like the millionth time to please see a doctor. Like always, he refused, spewed some particularly choice words at me, then hung up. I felt helpless and went on about my day.

RELATED: 12 Types of Depression, and What You Need to Know About Each

I had been concerned for months that his untreated schizophrenia, and the voices he said that constantly threatened him, would lead him to take his life. So although it is difficult for me to admit, when I found out about his death I was a tiny bit relieved. His life had deteriorated beyond recognition, and now his pain was gone.

When people talk about the stigma of suicide, it isn’t that we should be more tolerant of it. I don’t think anyone wants to live in a society in which suicide is considered a reasonable answer to life’s problems or a prognosis for serious mental illness. The stigma belongs to those who are left behind. People speak about suicide in hushed tones or avoid talking about it at all. It’s difficult to know how to mourn when the person who died wanted to be dead. It can make the people left behind feel even more alone.

Someone once asked me if I called 911 after I spoke to my brother the day he died. I did not. I didn’t even think about it. By that point, I had called the police, crisis hotlines, and hospitals many times, to no avail. But that question, innocent as it was, will stay with me for the rest of my life.

When someone dies, everyone wants to know the cause. If it was cancer, what kind? What stage? When did they catch it? We all want something to blame, whether it is an organ, an illness, or an act of violence. With suicide, you know how, but you will never know exactly why. So we often turn inwards to look for that cause, wondering if there is something we could have done to prevent it.

I do blame myself for my brother’s death. If I had called 911 after I spoke to him that day, would police all over Oregon start a search for a 21-year-old homeless man with schizophrenia because his sister thought he sounded extra weird on the phone? Probably not. If they had found him, would this be the one time, after several previous hospitalizations, that he agreed to take medication? But logic never wins when you play the “what if” game.

RELATED: What to Say—and What Not to Say—When You Talk About Suicide

More often, I wonder what might have happened if our family had understood the early symptoms of mental illness so that we could have gotten him into treatment before he became an adult. I blame us. I wonder if my brother would still be alive if the law protected him against himself, rather than protecting his rights. I blame the government. I hand out the blame in drips and drabs so no one bears too much. I know it isn’t really fair, but I want everyone to suffer a little bit because I am suffering so much.

Blame doesn’t help anyone, especially not me. By doing so I am internalizing the pain my brother felt, the pain he wanted to end. This is how the cycle of suicide continues. For every person who dies by suicide, researchers believe that 135 are so affected by the death that they need mental health treatment or emotional support. What’s more, a family history of suicide is a leading risk factor.

To prevent suicide, we have to stop stigmatizing survivors who are mourning not just death, but lives that were more painful than they should have been. As hard as it may be, we have to stop blaming ourselves, and others, for lives we could not save.

After my brother’s death, I’ve tried to make sense of mental illness by working at nonprofit organizations, including the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline. In all that I have learned, two incongruous things stand out above everything else. Suicide is preventable. You can help someone who wants to end their life find the support and treatment they need, but you cannot hold yourself accountable if they do not.

Ashley Womble is the author of Everything Is Going to Be OK: A Real Talk Guide for Living Well With Mental Illness.

To get our top stories delivered to your inbox, sign up for the Healthy Living newsletter