‘Bros’ flopped, but did it fail?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Evan Ross Katz is In The Know’s pop culture contributor. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram for more.

Is it good? It is. Let’s get that part out of the way right off the top.

“Bros Flops” read several headlines the weekend after the “groundbreaking” rom-com’s less-than-stellar $4.8 million opening weekend against its $22 million budget and a marketing budget between $30-40 million. Touted as the first of its kind — the first gay romantic comedy from a major studio — the film performed under 40% of its expected opening weekend, leaving many to ponder where it went wrong. Billy Eichner, the film’s outspoken star and co-writer, took to Twitter on Sunday night to thread his thoughts, shifting the blame for the lackluster turnout onto the audience, more specifically, “straight people, especially in certain parts of the country.”

He logged back in on Monday morning to throw more darts. “Tweeting about a movie you haven’t actually seen is meaningless… The majority of people who see Bros really love it!” There’s data to back up this sentiment, even if Eichner’s response comes off more defensive than explanatory. The film currently holds a 92% approval rating on Rotten Tomatoes, for instance. But great reviews and even great word of mouth do not a successful film make (just ask Steven Spielberg about his critically acclaimed West Side Story). And while opening weekend does not determine a film’s ultimate fate, the uphill battle for this film just got even steeper. That’s not to say it couldn’t have an Everything Everywhere All At Once-style trajectory, but that seems unlikely (we’ll get to why).

So sure, the film flopped if the metric is box office success. But did the film fail? Or did the film’s seismic ambitions, created by the studio and its star, limit its ability to be quietly great? Perhaps by attempting to appeal to everyone — ”I wanted it to feel real to gay men while also being hilarious and accessible to all audiences,” Eichner told Vogue — you appeal to no one. “In going after the widest audience possible, Bros may have fallen into a marketplace nether world — too straight for gay audiences, and too gay for straight ones,” some analysts posited in a New York Times postmortem.

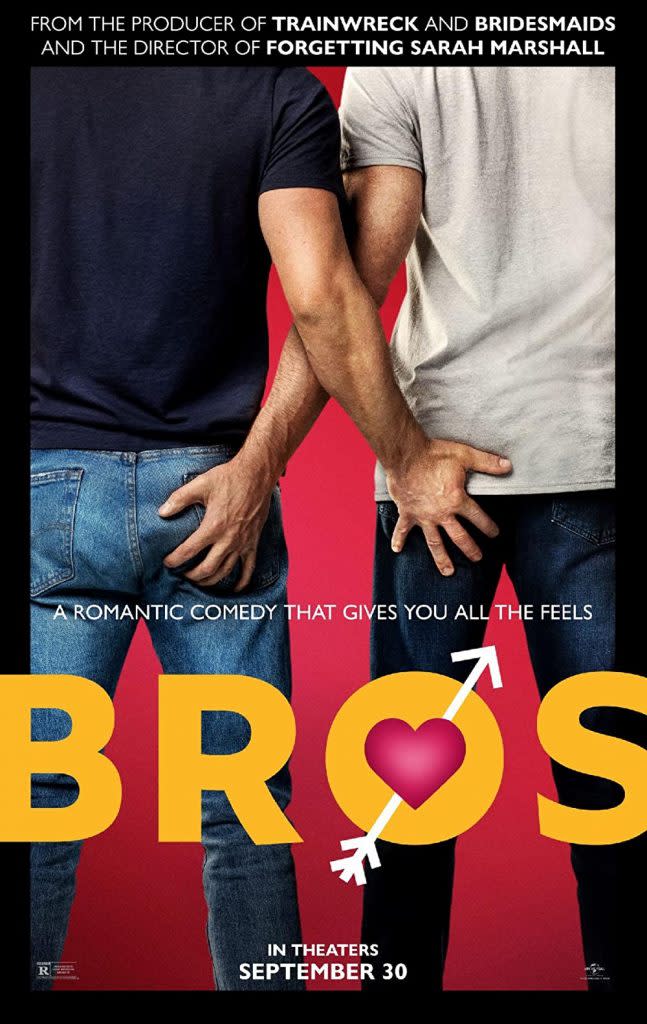

The marketing roll-out (budgeted higher than the production of the film) began in May when the trailer was first released and included festival appearances, Mariah Carey-hosted screenings, talk show appearances, magazine covers, the revival of Eichner’s Billy on the Street, tweets of support from stars including Ryan Reynolds, Jennifer Aniston, Seth Rogen and more, a lot more, over the five-month runway. And then there was the poster, plastered across buses, subway stations and any surface that could handle an adhesive. “A romantic comedy that gives you all the feels,” read the tagline, which was featured not over the faces or names of its stars, but instead the backside of two men, their hands gently cupping one another’s bums. Unlike Marry Me, a similarly budgeted rom-com starring Jennifer Lopez and Owen Wilson released earlier this year that featured not one but two J. Los on its poster, Bros opted for something more akin to Bruce Springsteen’s Born in the U.S.A. album cover than other films of its ilk.

A pressure point quickly arose over the messaging of the film when Universal first touted the film as “the first romantic comedy from a major studio about two gay men maybe, possibly, probably stumbling towards love.” Many, especially those in the queer community, were put off by the film’s effort to designate itself as historic, which disregarded a lineage of queer cinema — a canon that has existed for decades and represents a far wider swath of the community than Bros, a film that, though it might tell you otherwise, is ultimately about the love story of two cisgender white gay men, and ends with the pair centering themselves at a gala intended to celebrate the opening of a queer history museum. The film wanted to be another comedy in the lineage of Forgetting Sarah Marshall or Knocked Up (as explicitly referenced on its poster) while also wanting to carry the weight of representing an entire minority community — two herculean efforts that are both difficult to pull off and seemingly incongruous to one another.

bros flopping is crazy cuz why did it feel like billy eichner was under my bed BEGGING me to see that movie

— zae (@itszaeok) October 3, 2022

“We need to show all the homophobes like Clarence Thomas and all the homophobes on the Supreme Court that we want gay love stories, and we support LGBTQ people, and we are not letting them drag us back into the last century because they are past and Bros is the future,” Eichner told the screaming crowd at the VMAs in August. Suddenly, seeing Bros felt more obligatory than fun. The surrounding press didn’t always help, whether it be bungled interview quotes or hyperbolic headlines (“Billy Eichner Believes a Funny Gay Comedy Is the Best Activism”), all of which caused Bros fatigue at a time when the studio wants interest to wax, not wane (see: Don’t Worry Darling as another example of this phenomenon.)

Homophobia might play a factor in the film flopping, and certainly, the studio knew that would be a hurdle, but another factor, one with more concrete data, cannot be ignored: a genre long in decay. A March 2013 issue of the Atlantic asked the question: “Why Are Romantic Comedies So Bad?” The piece cited a decades-long decline that placed the blame on narrative laziness and not on waning interest. In the decade since, there have been runaway successes (To All The Boys I’ve Loved), but they’ve largely been relegated to streaming. Even rare theatrical outliers like The Lost City relied heavily on its stars and not on the names of its producer or groundbreaking concept. So here was Bros, attempting to both pay homage and subvert a genre that’s rarely given a theatrical release, without any big stars attached and in October of all months, positioned against a horror film, Smile, during the first weekend of spooky season. (Why was this movie delayed from mid-August to the last day in September? Why was it not released, say, during Pride month?)

For what it’s worth, the studio seemed aware of the odds stacked against them. “The rom-com genre has largely migrated to the streamers, and so that’s actually, I think, the bigger thing to overcome in a lot of ways, bringing a rom-com out in a muscular way,” Michael Moses, Universal’s chief marketing officer, told the New Yorker. There it is — an acknowledgment that consumer behavior has changed. Which begs the question, would this movie not have perhaps fared better on streaming? All of this attention could surely have converted public interest to people actually wanting to see what the brouhaha was about without the barrier of a ticket price or having to leave the comfort of one’s home. Controversy can be for the bottom line, just ask someone who no doubt did not see Bros over the weekend: Dave Chappelle.

But perhaps there’s a lesson here on how a film like Bros, a film worth seeing, could have been positioned better. Eichner’s tweet blaming straight people for the lukewarm opening, as well as campaigns like the “STRAIGHT PEOPLE GO SEE BROS CHALLENGE,” for instance, would lead one to believe that the studio was relying on straight people to make the film a hit. It makes sense, considering LGBTQ people make up only 5.6% of the population. But herein lies the conundrum of wanting to take the gay experiences of dating, having sex and falling in love and packaging and marketing it for mainstream consumption: Gay audiences can feel the story about them isn’t necessarily for them. And that’s an important oversight when discussing Bros.

Take, by contrast, Crazy Rich Asians, another film with historic designations of its own. For Warner Brothers President of Worldwide Marketing Blair Rich, the first priority when it came to marketing the film was wooing Asian Americans. To do so, she and her team worked with organizations like the Asia Society and the Coalition of Asian Pacifics in Entertainment. “You have to give them ownership of their story and then broaden it out from there,” she told the Hollywood Reporter about the strategy. Bros, in contrast, focused on getting butts in seats — any butts — as opposed to earning a sign-off from the community it was intending to uplift.

Or, perhaps still, there’s a more melancholic vantage point on why queer people didn’t rally behind the film in the same way they did around Fire Island, a gay rom-com released during Pride month. As Stacey D’Erasmo wrote in 2004 review of Showtime’s The L-Word: “A peculiar consequence of so rarely seeing your kind on television, in movies, in plays, what have you, is that you can become, almost unwittingly, attached to a certain kind of wildness: the wildness of feeling not only unrepresented but somehow unrepresentable in ordinary terms. You get so good at ranging around unseen that it can feel a little limiting to be decanted into a group of perfectly nice women leading pleasant, more or less realistic lives. You can think, ungratefully: Is that all there is?” Perhaps this is why angst has grown from one quadrant of the queer community who fault the film’s lack of success not on straight people but on the community’s lack of support of its own. And perhaps they’re not wrong!

Now that the film has flopped, at least from a money-generating perspective, does this diminish the chances of the second gay rom-com from a major studio? Or is the lesson here that perhaps LGBTQ stories don’t require major studio backing to get made or to get seen in an era where streaming can cast a wider net of prospective viewers? Or should Bros not be looked at as any kind of bellwether on the future of queer storytelling?

Did Bros fail, or did Bros get in the way of its own success?

If you enjoyed this article, read what Evan Ross Katz thought about “Bros” before it came out here.

The post ‘Bros’ flopped, but did it fail? appeared first on In The Know.