British Painter Danny Fox’s Star Continues to Rise

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

When I met the artist Danny Fox four years ago, he was living in downtown LA and making work that drew heavily from the hardscrabble Skid Row world that enveloped him. It was a world reminiscent of the LA of John Fante or Charles Bukowski, populated by barflies, burnouts and shabbily elegant coulda-shoulda-wouldas. But as a guy from England, his Britishness seemed to give him a compassionate outsider’s view of things.

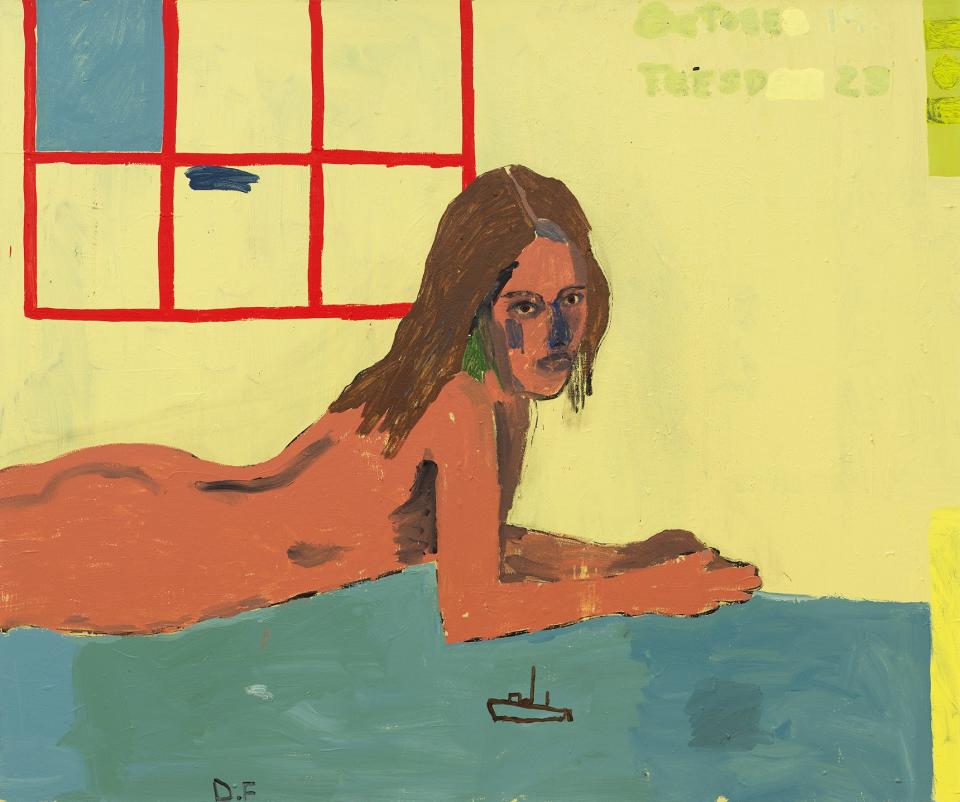

Fox’s canvases use a vibrant array of colors that are tempered, or appear worn down, evoking the shadowy natures of their subjects. A skillful tightrope walker, Fox operates as both observer and participant: on a cellular level, the canvases convey that the artist is deeply intimate with the kind of life, always lived outside the ordinary, that he depicts. At the same time, the structures of Fox’s compositions indicate an understanding of the painters and paintings that have come before him. The resulting work exudes a visceral synergy. "I think Danny’s work speaks intuitively to many of us because it's firmly rooted in the long lineage of painting,” says Jesper Elg, director of Copenhagen's V1 & Eighteen galleries. “When he paints a horse, I feel instantly connected to painting as a language, going back to the paintings in the Chauvet caves 30,000 years ago. He invests in, and engages this painterly language, bringing it into the realm of the contemporary.”

And then, like Monet saying au revoir to the Lily ponds, Fox left downtown LA. He didn’t go far: a little more than a year ago, Fox moved to a house in Bronson Canyon, a stone's throw from the tunnels where the original Batman TV show credits were shot. "I just ran out of juice downtown,” Fox says. “I started to see what everyone else saw, the sadness and the pain instead of things to paint. And I felt like my luck had run out too. I used to walk around Skid Row at all hours like I was bulletproof, then I got into some sticky situations and felt like it was time to move on.” But it wasn’t just a matter of personal safety, says Fox: “Above all else, it was about the work. I didn’t want to repeat myself."

Currently, Fox has two shows up, the first at Copenhagen's Eighteen Gallery, and the second, titled “The Sweet And Burning Hills,” at Alexander Berggruen in New York. Both display the shift in Fox’s technical perspective that came with his move, along with his new subjects, a cadre of slightly more polished canyon dwellers: Tali Lennox, Dylan Penn, Langley Fox, Lorraine Nicholson. With the exception of his friend and fellow artist Honor Titus, his new muses are female, and predominantly daughters of Hollywood—the type that embody a particularly beautiful sense of Los Angeles ennui.

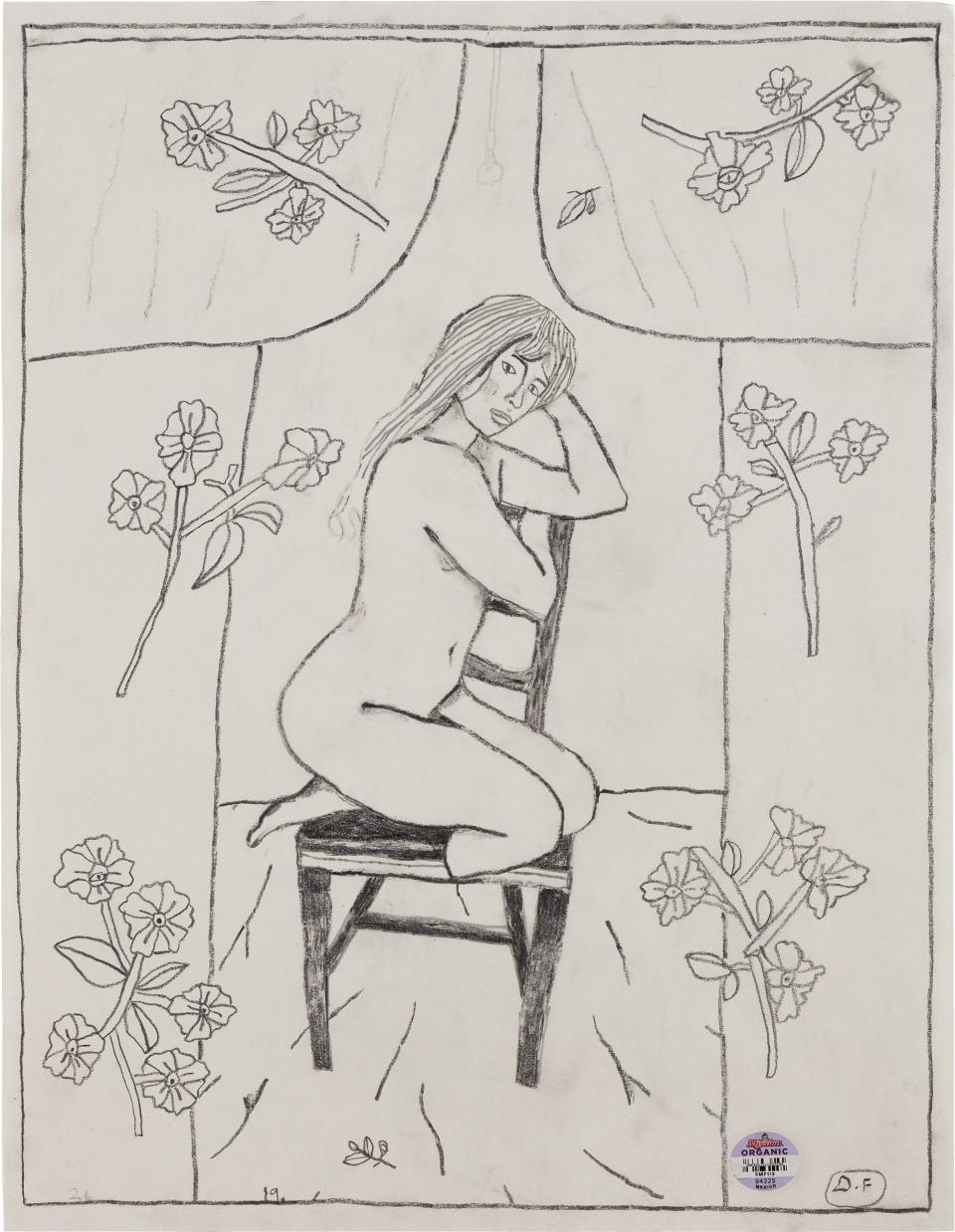

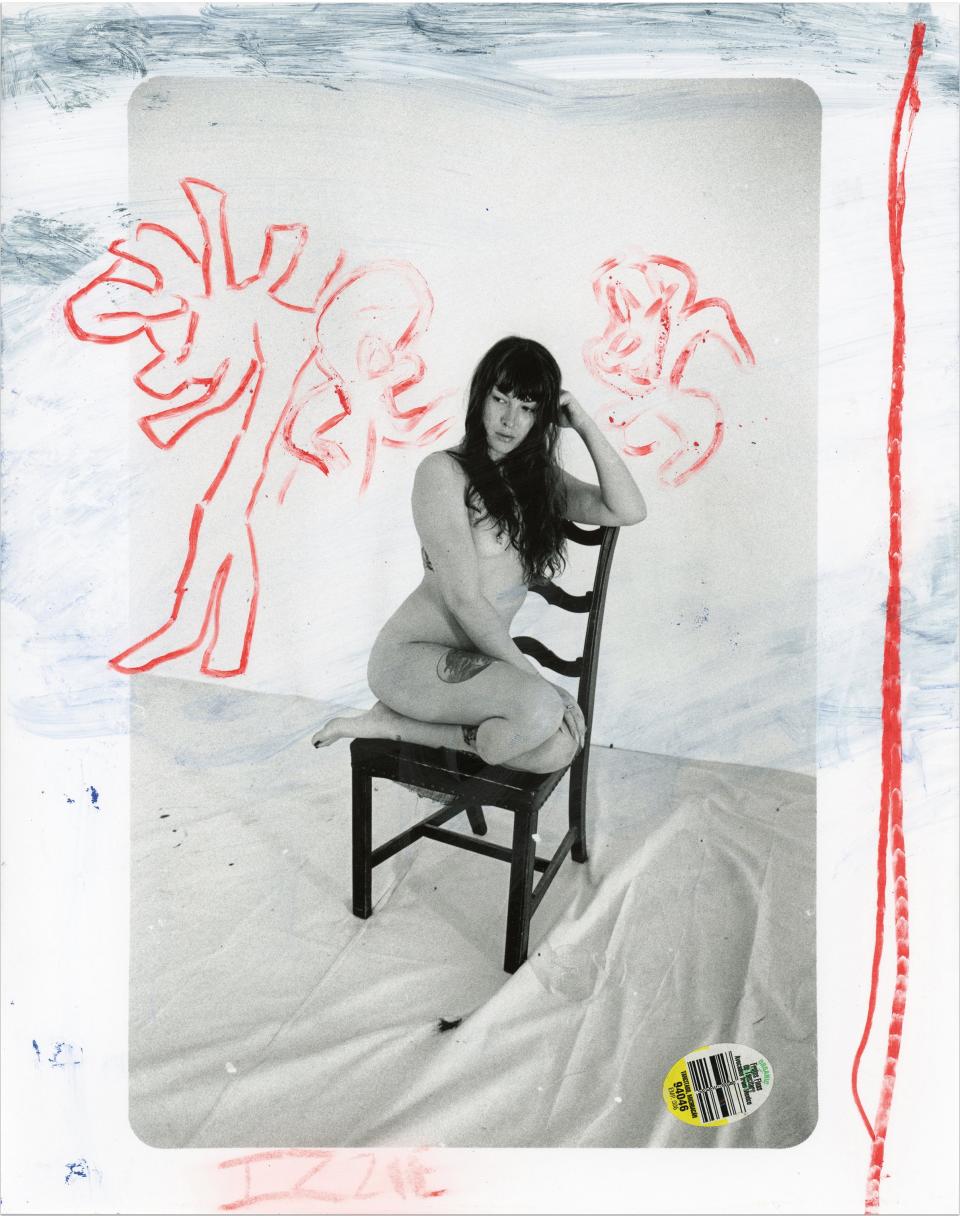

Invigorated by the shift in perspective as a result of his change of venue and setting, Fox decided to raise his ante, cultivating a multi-medium process involving photos, drawings, and paintings which yield visual bombs at each juncture. The subjects posed at Fox's house, sitting for photographs and drawings—which then became the source material for full-scale paintings.

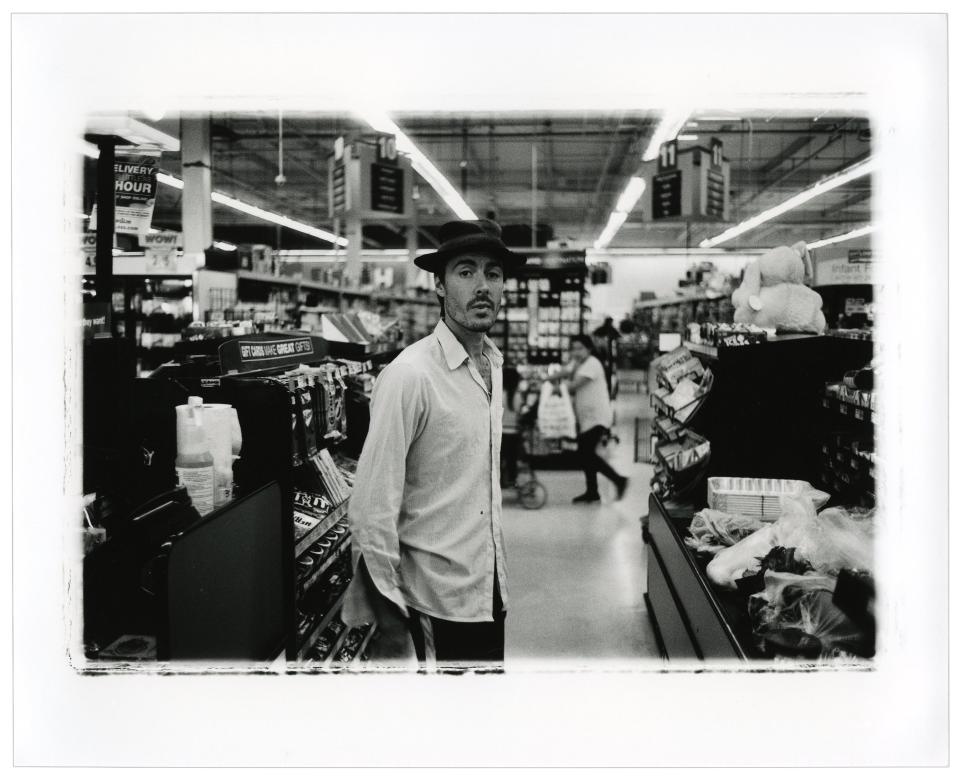

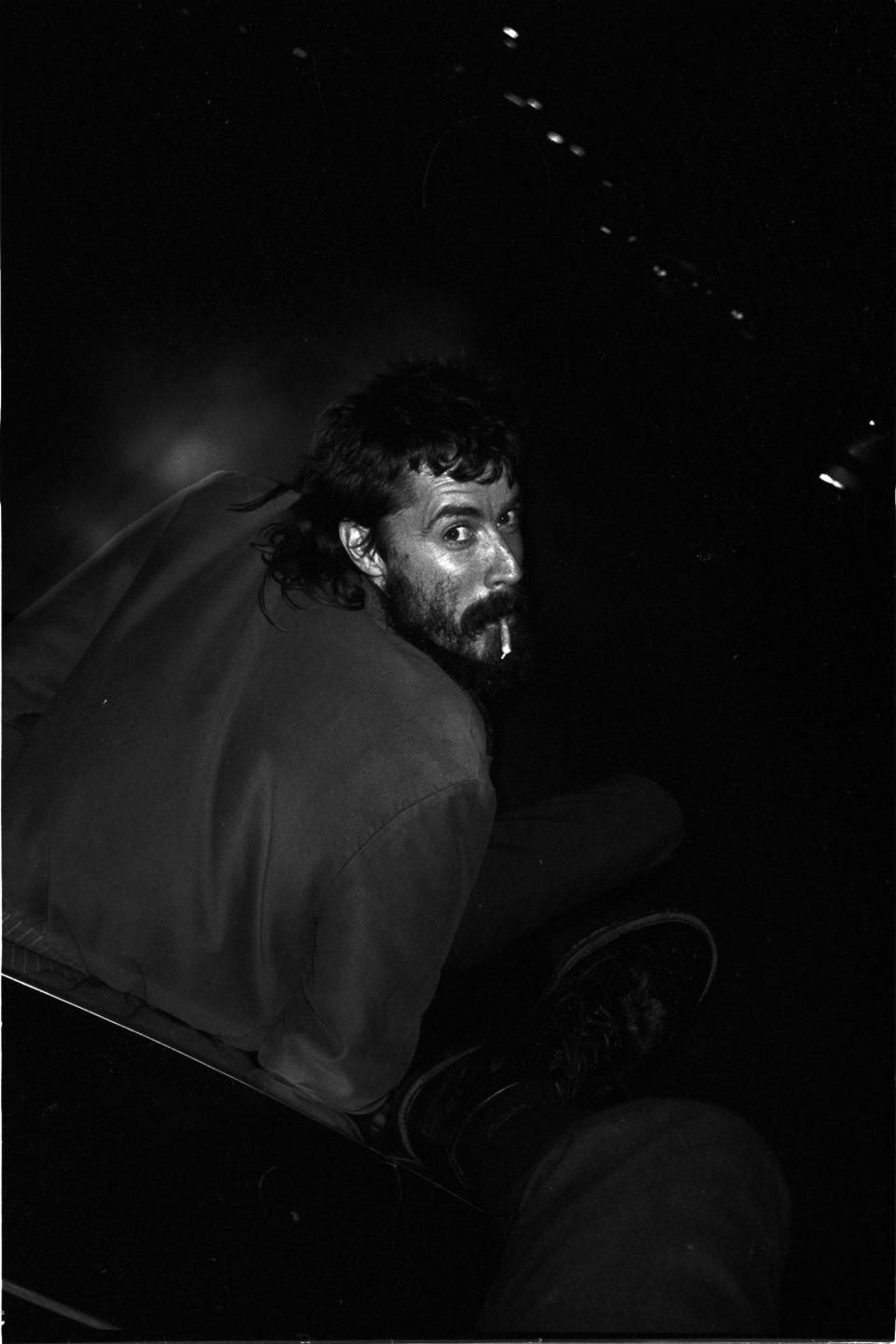

For the photographs, Fox enlisted old friend and collaborator Kingsley Ifill to capture his new studies. Ifill's photos were developed on the spot in an ad hoc dark room which Fox then minimally embellished with discarded produce stickers, text, and marginalia. The young, sinewy figures occupy the sparse, arid desert backdrops that allude to canyon compounds of days gone by, be it the Laurel Canyon Mamas & Papas clan, or further west to Spahn Ranch and the Manson kids. Fox's drawings then reference Ifill's portraits but take on a life all their own, benefitting from the artist's pared-down lines and quiet disregard for perspective. (Both the photographs and drawings are up now at Eighteen in Copenhagen, and provide material for an enthralling accompanying book, “Eye For A Sty, Tooth For The Roof.”)

Fox’s show at Berggruen, meanwhile, consists of paintings that echo those photos and drawings—an oozing array of opulent canvases organized around solo figures. Mostly female, the characters smoke, they straddle stuffed animals, they clasp their knees in seductive disdain, they eye us with casual contempt, they sprawl out across the floor or invite us to follow them deeper into the canyon.

A signature of Fox’s work is to use snippets of text both inside and outside of his frame. "His writing leaves clues for a viewer to piece together and serves as a sort of primer for the experience one might have viewing his paintings,” says Alex Berggruen. “Some writing even works its way into the paintings themselves." In one painting from “TSABH,” a wayward brunette sits on a simple chair, a pie missing a single slice at her feet, the text “HOUSE OF PIES” running along the base of the composition, a melancholy nod to the neighborhood’s last remaining classic diner and the nighthawks it feeds.

Taking in the new body of work he’s amassed, I mention to Fox that it feels not unlike a great album, where the work conveys a single moment but also evokes an entire journey. “I always think of shows as albums,” says Fox. “I use that to help encapsulate certain moments and not worry if it’s off brand. I even sometimes think, Ah, shit, I’m making a bad album here. But I also like that feeling—like it’s going to be the ’80s Dylan album that you one day understand."

Originally Appeared on GQ