The year that British cinema went sex mad – and struck box office gold

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

If you were to picture a classic world-cinema location that shimmered with erotic promise, your mind might not immediately turn to the shopping parade on Shenley Road in Borehamwood. But the 1970s was a very different time.

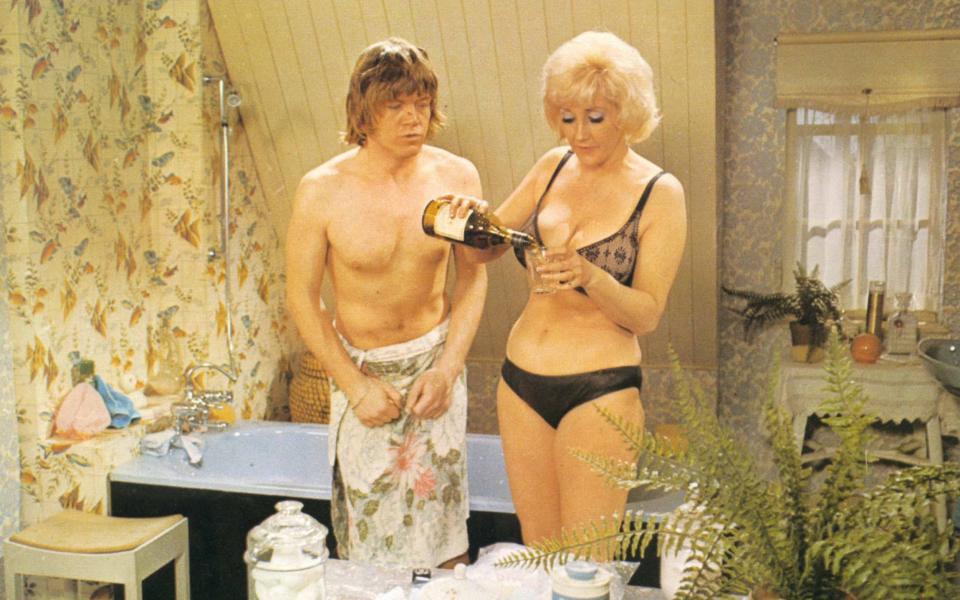

This backdrop of mesmerising grottiness is where, 50 years ago, cinema-goers first met Robin Askwith’s Timothy Lea – the hero of Confessions of a Window Cleaner, happily cycling along with a ladder slung over his shoulder and an extendable squeegee in his trousers. The first of four films about this grinning Jack-the-lad’s cartoonish sex life, Confessions of a Window Cleaner was a colossal box office hit, out-grossing every other British film released that year.

And this was no one-off knee-trembler behind the bicycle sheds. In fact, sex comedies were almost single-handedly responsible for keeping British cinemas upright, so to speak, for the entirety of the 1970s. The Confessions series’ success rivalled that of the James Bond films – and were originated by Bond screenwriter Christopher Wood, who wrote the smutty novels on which they were based.

In 1976, more Brits went to see Adventures of a Taxi Driver than Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver. Come Play With Me, featuring genre icon Mary Millington, ran for a record-breaking 201 weeks at London’s Moulin cinema, and played on 1,000 screens nationwide.

Today, however, these films are treated like a national dirty secret: rarely talked about and barely rewatched. Some notable lone voices like Simon Sheridan and Matthew Sweet have recently tried to argue the case for their importance – if not their quality. But otherwise, like the death of the drummer John ‘Stumpy’ Pepys in This Is Spinal Tap, the staggering popularity of the British sex comedy is regarded as a mystery best left unsolved.

But 50 years after Askwith first sprung out of his y-fronts, perhaps we should try to solve it – or at least shin up the drainpipe, peek through the lace curtains, and marvel at these things’ vigour and bounce. Cinema in Britain was in a bad place back then. The advent of colour television had caused admissions to plummet, from 193 million in 1970 to a mere 110 million 10 years later, while the crumbling of Hollywood’s old studio regime starved our own industry of vital investment.

Once-popular franchises like the Carry On and Doctor series had burned themselves out in the 1960s, and all of the ambitious new home-grown work, from young blades like Nicolas Roeg and Ken Russell, was too experimental for the mass market. Only feature-length versions of popular sitcoms, like Up Pompeii! and On the Buses, still seemed able to pull in a crowd.

The solution, at least in the short term, was to offer audiences something that looked and behaved a lot like the things they loved watching at home, but had no chance in hell of being broadcast. As their titles often suggested – Secrets of a Door-to-Door Salesman, The Ups and Downs of a Handyman, The Amorous Milkman, and so on – these were comic stories typically about young working-class men whose jobs afforded them ample opportunity for sexual relations with the sort of women and girls the class system would otherwise keep out of reach.

The salacious potential of the window cleaner’s trade had already been formally identified by George Formby in the 1930s, but the strain of British humour concerning randy young men, bored posh housewives, ladders and bare bottoms at windows runs all the way back to Chaucer. It feels telling that when Pier Paolo Pasolini adapted The Canterbury Tales, for one of his leading men he chose Robin Askwith.

Yet while the sex comedies were made in the same increasingly permissive times that allowed European provocateurs like Pasolini to push the limits of what could be seen on screen, they were in many respects deeply conservative. Yes, they featured endless shots of jiggling boobs and bums, and sometimes more. But sex here was only a lark – a momentary blip in the status quo, with order typically restored by the middle-aged husband blundering in after getting off unexpectedly early from work. It also wasn’t sexy at all, but rather messy and embarrassing – trysts were impeded by spilled washing-up liquid and garter-belt mishaps, and infiltrated by pythons on the loose.

The formula was robust, but in some respects also surprisingly fragile. The second Confessions film, in which Timothy Lea becomes a Pop Performer, was less successful than Window Cleaner, but the third, Driving Instructor, rallied the crowds. Like a good juicy News of the World scandal – and like a lot of mainstream pornography today – the implication was not simply that somebody somewhere was partaking in exciting sex, but that there was an entire hidden world just underneath the visible one in which everyone was constantly having it off.

These films’ extraordinary profitability proved that Britain in the 1970s was gagging for this stuff. But their rise was only made possible by an adjustment to the X certificate in April 1970: a new lower age limit of 18, rather than 16, meant that raunchier, more violent material could evade the censors’ snippings. Censorship in Britain was still considerably tighter than in Europe or America – the mainstream US success in 1972 of the hardcore film Deep Throat could have never occurred here – but nudity had been permissible for a while for allegedly educational purposes.

As such, the first film to be passed under the new X regulations was The Wife Swappers, a largely fictional exposé of the suburban swinging scene produced by Stanley Long, who had spent much of the 1960s making naturism documentaries with titles like Nudes of the World and Take Off Your Clothes and Live. But the shift to comedy presented blushing customers with an even more plausible fig leaf at the ticket desk. Rather than supposedly wanting to learn something, they were simply there to have a laugh.

While the public flocked to these films, critics openly loathed them, and morality campaigners were appalled. In 1975 a BBC Two documentary titled X-ploitation shed a light on the often seamy circumstances in which they were made, and issued dire warnings of a nationwide collapse in morals. But its arguments can’t have been that persuasive, because the month after it was broadcast, its director left the BBC to make sex comedies.

Besides, by then, the genre was already established enough to have earned its own spoof: Eskimo Nell, which like Confessions of a Window Cleaner celebrates its semicentennial this year. Directed by Martin Campbell, who would go on to make GoldenEye, Casino Royale and two Zorro pictures, it did for the British sex comedy what The Producers did for Broadway musicals, squeezing in just enough T&A to qualify as the very thing it was sending up.

Like most strands of exploitation cinema, the British sex comedy was killed by the advent of home video, and the national film industry was forced to smarten itself up. (As the old joke goes, British cinema of the 1980s was full of people who were rich, sad and gay because the previous decade had burned everyone out on the alternative.)

Do the films hold up today? Like the man who claims to read Playboy for the articles, I’m going to suggest they remain amazing social documents, which offer an eye-widening look at the often thwarted desires of the time, as well as the bosoms. To revisit them is to dip back into a Britain where ordinary life was a slog, and pleasure had to be pilfered wherever you could get it.