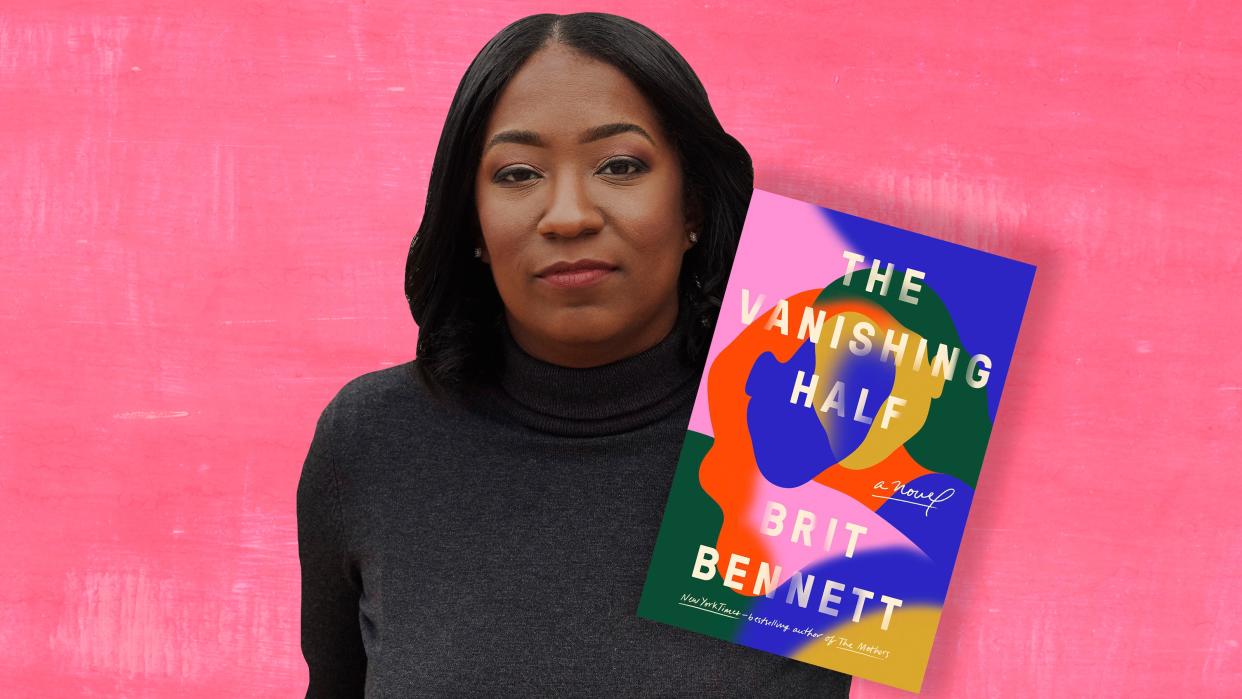

Brit Bennett on Her New Novel, Favorite Writers, and Zoom Fatigue

Few debut novelists receive the accolades that followed the publication of Brit Bennett’s The Mothers. The novel, which she began writing while still an undergraduate at Stanford University, became a New York Times best-seller and was optioned by Warner Bros., with Kerry Washington signed on to produce. With the publication of The Vanishing Half, Brit Bennett’s critical and popular appeal continues to soar. Her second novel—also a near-instant bestseller—became the subject of a 17-way auction; HBO secured the rights to develop the book into a limited series.

The inspiration for The Vanishing Half came from Bennett’s mother, who recalled a town from her childhood in Louisiana “where everyone intermarried so that their children would get lighter. It was a very disturbing idea, and it struck me immediately as a setting for a novel,” Bennett tells me. The novel follows two sisters from the fictional Louisiana town of Mallard, where the Black inhabitants pride themselves on their light skin. The Vignes twins, Desiree and Stella, leave town at 16 only to separate when Stella abandons her sister to live as a white woman.

After I finished The Vanishing Half, it was clear what inspired the studio frenzy. The novel, which spans the 1950s to the 1990s, feels epic in scope. Yet when I got to the end, I felt I had gotten to know the characters so intimately that I was relieved to learn they’d be reborn on screen.

Since her book was recently released during a pandemic, Bennett, like myself and other writers, has moved her tour online, which has yielded new challenges and pleasant surprises. She spoke to me by phone about her new novel, her writing process, and how teaching helped her cope with living alone during the pandemic.

Glamour: Congratulations on selling the rights to The Vanishing Half to HBO. I read that you’re going to be listed as an executive producer. Do you know how involved you’ll be in this show’s development?

Brit Bennett: Honestly, I don’t know. I’ve never been in this position before. Right now I’m involved in helping decide who is going to be the person who actually writes the show. Perhaps unsurprisingly, that’s the part that I’m really excited about. I think I’ll be involved in consulting on different areas, but I’m actually really excited for us to find the writer and to hand the story off to that person and let them translate it through their own creative vision.

You wrote and sold the screenplay for The Mothers, right?

Right. Yeah, I adapted that one. I wrote a draft of that screenplay.

Do you plan on being part of the writers room for The Vanishing Half at all, or would you like to be?

No, I found adapting my own work to be extremely hard. You know, a lot of people will tell you that going into it, and it was certainly something that I felt was true. So I’m very happy to leave this to the professionals and just to weigh in as needed.

Do you have any concerns about the show’s potentially deviating too much from your novel?

No, I don't have any concerns. I think all the writers that we’re talking about are geniuses in their own right. And at the same time, I have lived with this book for so long that I’m excited to see how somebody else is going to interpret it. I don’t want a writer who is just going to parrot the book back in the way that I wrote it. I want somebody who’s going to do something different with it. So I’m excited. They’re all brilliant writers, and I’m just excited to see who’s going to be at the helm.

Do you know where they are with the production of The Mothers?

I don’t. That’s kind of in the hands of the development gods right now. The studio is still very excited about the project, so we’ll see what happens. It seems like all of Hollywood has ground to a halt right now. So I don’t know if there will be any updates anytime soon. But I was grateful for the experience of writing a screenplay, which I had never done before.

I’m curious about your writing process. I’m working on my second novel now. I wonder how your process changed between The Mothers and The Vanishing Half. Was there anything you learned from writing your first novel that made writing the second one a little easier?

I don’t know if it made it easier. I think second novels are really hard. I think one thing that felt different was that I was able to spot bad ideas sooner. With the first novel, I would be hung up on a bad idea, and by bad I just mean wrong for me, wrong for the novel, wrong for the character. Not necessarily intrinsically bad, but just not the right fit. With my first novel I would go down that road that was ending nowhere, and I’d be going down the road for years. With this book, after a few months, I was able to redirect myself a little bit more easily. So I was proud of that. But I kept thinking, Well I’ve written the first novel, why am I struggling so much with writing the second one? I remember one of my friends just said, ‘Well, you've never written a second novel before.’ It’s sort of a cliché, but it’s true that each book requires something different from you. It becomes its own process. I imagine if you had written 10 novels, that the 11th novel is going to still be its own challenge.

What was your research process like? Did you find the real town that was similar to Mallard?

I found other communities like that in Louisiana, these light-skinned creole communities, but most of the backstory of Mallard I made up, I invented. I read some articles on Jstor, these sort of sociological types of articles about these tiny communities of very light-skinned Black people that were sort of separate from the white world and also from the larger Black community. I was able to draw on some of those to make the town feel grounded, but I also just really had fun inventing this new place.

The book spans such a long period of time, and it really shows the impact of the civil rights movement on the lives of Black Americans. You can see the radically different opportunities open to Jude, Desiree’s daughter, compared with the ones open to Desiree and Stella at the start of the novel. At the same time, it’s poignant that Stella obviously still sees the benefit of continuing to pass as white even through the ’80s. You also show the struggle the characters face beyond race—their struggles as women, as LGBTQ people, as working-class people. I was wondering if you knew from the beginning what historical movements you wanted to tackle or did you just end up touching on them organically?

I think it was more organic for me. I knew the time period in which I wanted to open the novel would be somewhere mid-century. I knew that I wanted to write the story at some point in the past because I was engaging with Jim Crow. And also, I just think it’s more interesting to write a story about a missing person when it’s set before Google, before Facebook. I don’t consider myself a historical novelist or one of these writers who engaged very deeply with the details of history. I just really think of the history as backdrop and how these historical moments inflect the lives of these characters. I knew that the book was going to be set around this period of dramatic social and political change in America when it comes to race, gender, and sexual orientation. I knew that it was going to reflect on the characters in an interesting way. I also just really love the idea of Stella choosing to pass in that moment in which all of these categories are shifting in a way or they’re becoming more complicated. I love the idea of her making this big, dramatic decision to be this completely different person at a time in which the world itself is continuing to shift.

Usually when I write a novel, each new draft gets progressively longer. I’m not somebody who ends up cutting a lot of content. This novel isn’t very long, but I felt like you knew the characters so deeply. I could imagine that there was so much more about them than what was written. Was there even more backstory that didn’t make it into the novel?

It definitely expands and contracts for me. I don't remember any specific scenes or moments that I really cut, but often it’ll balloon and then eventually I’ll compress. I had this professor when I was an undergrad who referred to it as “heighten and tighten.” Once you know what the story is, heightening all the emotion, heightening the drama, the stakes, all those things, and then just tightening it. I think of that once I’m deeper into the process. Once I know the parameters of what I’m working with. There was a lot of stuff I remember I cut from The Mothers. I think The Vanishing Half is a bit more sprawling. I don’t think that I was ready when I wrote The Mothers to write something quite that sprawling. There were all these things that I was thinking about, but I think my ambition was a little bit beyond my abilities at that point. I think to write a book that was a bit more sprawling, I had to spend another five years trying to learn how to do that.

I read that you moved to Brooklyn to teach. I was wondering if you find that when you’re writing a novel, teaching is helpful or a distraction from writing?

I love teaching a lot. I’m not teaching this upcoming semester, but I had a blast teaching this last year. I thought it did feel helpful to have to think about your process when you are explaining it to somebody else. I think there’s something about having to actually think about it consciously and articulate what you value and what you think works in fiction. There’s something about what teaching requires of you that feels really generative. I also think just being in a room with a bunch of people and talking about work, and reading your students’ work, felt creatively very generative. I was bummed when my class went on Zoom during the pandemic, but that class was so vital during that time. I was quarantining alone, and I remember that the first week after our class ended was my lowest point, not having my students who I was engaging with every week. I was so grateful for our Zoom workshop because it really did help keep me creatively engaged and mentally stimulated during that period of just being at home, but it also kept me sort of emotionally and psychologically well during the beginning of quarantine.

Who are some of the writers who have influenced you?

My big ones are Toni Morrison and James Baldwin. I also really love Dorothy Allison, Jesmyn Ward, and Maggie Nelson. I just love writers who are intelligent but also write things that move you. I really want to be moved when I’m reading something, not just stimulated intellectually. I want a book that works on both planes.

We have both had the experience of launching books during a global health crisis. How have you been adapting to virtual events so far? Do you think you’ll continue doing them after social distancing ends?

The biggest surprise to me is that I thought this was going to be easy. Book tours become physically exhausting, just being on planes and everything, [but] the virtual aspect of it means the tour does not have to come to an end in two weeks. I hope that the life of the book and the idea of the book launch will be kind of reinvented through this experience because it’s not something that’s restricted to place and time anymore. I do think that it requires energy from you in a way that’s very different from being in a room with people. I would feel very tired when I got off Zoom. There’s a process of giving energy you’re not really getting back because you’re talking to your computer screen. It’s a different way of engaging with readers. I hope that it’s not the end of the book tour because I think book tours are fun and also just a great opportunity to see all of your friends and family and to meet readers to sign books. I’ve met so many great booksellers. I hope that what remains in our post-pandemic lives is this idea that these events can be more accessible by making them virtual.

Your book came out after the George Floyd protests began. Since then I’ve gotten quite a few requests to write about race or my feelings about the current moment. Your book is obviously about race, but I was wondering if you feel a sort of pressure to recontextualize your work so that it speaks to this current moment.

A little bit. I think that the way that it popped up most for me was people wanting to connect it to the anti-racist reading list. I guess it’s fine if this is how you read this book, but I sure hope nobody is reading this book in hopes that they will learn how to be anti-racist. That’s not the context in which I wrote it. I’m not equipped nor interested in teaching anybody how to be anti-racist. There are some writers who are educators. Their work is about educating. My work is not. My work is stories. I’m interested in just telling stories that are interesting and engaging and hopefully will make you feel something deeply and think deeply.

Maisy Card is the author of the novel These Ghosts Are Family, which was published by Simon & Schuster in March.

Originally Appeared on Glamour