A Brief History of the Salmon Dial—and Why Yours Probably Isn’t One

As with many trending watches, a whirlwind of recent marketing hype has strewn the facts about salmon watch dials into the algorithmic noise of the internet. However, regarding this tiny pink corner of horological interest I’m confident that we can establish some facts—if not consensus—about the elusive salmon dial.

Regarding consensus, there is very little over salmon dials. Opinions of these pinkish-gold watch faces vary, of course, but hotter arguments rage over what constitutes an authentic salmon dial. In the academic sense, authenticity requires establishing direct links to origins, which is what this story aims to do.

More from Robb Report

IWC's New N.Y.C. Boutique Is an Espresso Bar That Doubles as a High-Tech Watch Atelier

How Rolex Became King: A Brief History of the World's Most-Renowned Watchmaker

A $17.3 Million Patek Philippe Minute Repeater Leads Only Watch Auction

However, I should state at the outset that I believe that there is just one “real” salmon dial color derived from just one “correct” production technique. My opinion stems from experiences with vintage salmon dials from Patek Philippe and Vacheron Constantin that reign among the most beautiful watch dials I’ve ever seen. However, my goal here is not to sway opinion or assert my snootiness, but to straighten out some of the knotted history of salmon dials with the hope that we may all better inform our individual opinions.

What Exactly Is a Salmon Dial?

Though we will learn of other ways of making salmon-colored dials, the original method—and the one I submit is authentic—involves electroplating gold onto a metal dial (usually brass). Electroplating was invented in Italy in 1805, and so we sometimes see pocket watches with electroplated salmon dials from that century, and these are almost always housed in rose gold cases for tonal consistency. By the 1920s, we begin to see electroplated salmon dials inside platinum and white gold cases, which obviously emphasizes contrast, and this pairing was very popular by the 1940s.

These salmon dials were far less common than electroplated silver dials (often called “silvered” dials). Many companies, including Patek Philippe and Vacheron Constantin, have reserved salmon dials for VIP clients, and even today the properly electroplated salmon dial remains relatively rare.

The term “salmon” is a rather recent name for what are more traditionally called “gilded dials,” or in French, cadran doré. When exactly the term “salmon dial” emerged remains unclear, but it wasn’t all that long ago. (I’m just old enough to recall hearing that term sometime in the 1990s or early 2000s, but not before.) Historic companies like Patek Philippe still refer to gilded dials, while younger brands—or those surfing the trend—tend to speak of salmon dials.

Salmon is a rather specific color, and there’s much confusion and disagreement about it. The exact color of any gilded dial is derived from the amount of copper added to the yellow gold that is electroplated to the dial. I subscribe to the idea that there is just one gold formula that derives the special pink color we can legitimately call salmon: That being 3N gold.

In metallurgy, there are standardized numbers indicating copper content, with N1 indicating straight-up yellow gold and higher numbers indicating more and more copper. The 2N designation indicates a paler rose gold, 3N the color I would call salmon, 4N for pink gold and 5N for red gold. As you can see, a 3N salmon dial occupies a very specific shade between rose and pink gold. Though not all brands adhere to an exact 3N formula in creating electroplated gilded dials, the 3N gold formula is generally accepted as 75 percent gold, 13 percent silver, and 12 percent copper.

While some of you may not agree with my strict notions, so far none of the above is terribly confusing. However, there’s much more to consider when it comes to the elusive salmon dial.

The Confusion Over Opaline Dials

Some of you will have heard salmon dials referred to as “gold opaline dials” or “gilded opaline dials”—and you may very well have heard of “silvered opaline dials,” which are especially common in watches from Cartier, but also Vacheron Constantin, A. Lange & Sohne, Piaget, and many more. The term opaline creates a lot of confusion, so let’s work through it.

Opaline—which is named after the well-known opal mineraloid—is a milky art glass streaked with gentle iridescent overtones. Opaline glass originated in Murano, Italy and became especially popular in the Art-Deco era, precisely when wrist watches were the emerging trend.

The term “opaline dial” is confusing, because it suggests that the watch dial is made from this milky art glass, which it most certainly is not. Opaline is simply a description of the somewhat iridescent color achieved through electroplating dials with silver. My Cartier Tank and two of my vintage Vacheron Constantins, for example, sport silvered dials that are especially lovely in this regard, and their iridescence is due to the granular texture of the silver coating, which casts subtle shadows and gentle reflection.

This granular texture of the electroplated coating is, in my opinion, a key determining factor of the illusive beauty of silvered and gilded dials. These dials create a soft, matte, and subtly iridescent surface. Under a loupe magnifier, one can see the granular texture of the electroplated coating, and at arm’s length one sees a softness, depth of color, and slight mimicking of the hue of the ambient light.

While some watchmakers electroplate silver and gold onto engraved and brushed dials, the strictest among us would likely agree that a flat dial with granular silver and gold is (a) what is usually meant by “opaline” and (b) the best way to show off the soft iridescence of these electroplated metals.

The problem with the term opaline, however is that it does a poor job of describing gold dials, which, due to their color, look nothing like opaline art glass. A gilded opaline dial simply takes its name from silvered opaline dials, even though the phrase “gilded opaline dial” makes little sense. So goes the often-odd naming conventions of horology.

The Confusion Over Galvanizing

As if all this wasn’t confusing enough, there is another semantic knot to untangle regarding the difference between electroplating and galvanizing. In English, galvanizing is only used to refer to adhering zinc to steel. But in French the word for electroplating (of silver and gold, among other metals) is galvanoplastie. When speaking English, French-speaking Swiss folks will in all sincerity refer to “a galvanic gilded opaline dial,” which absurdly suggests they’ve galvanized gold (which is not a thing) onto opaline art glass (which is impossible). I will admit that a “galvanic gilded opaline dial” sounds lovely and technical, however, so I see the appeal of this absurdity for marketing copy.

So, to be exceptionally clear about all of this for us English speakers: There is no opaline in opaline dials; there is no galvanizing in galvanic dials; and what the phrase “salmon dial” should refer to is a flat metal watch dial onto which a layer of 3N gold has been electroplated.

But, of course, nothing in the world of watches is ever that simple.

‘Salmon-Adjacent’ Dials

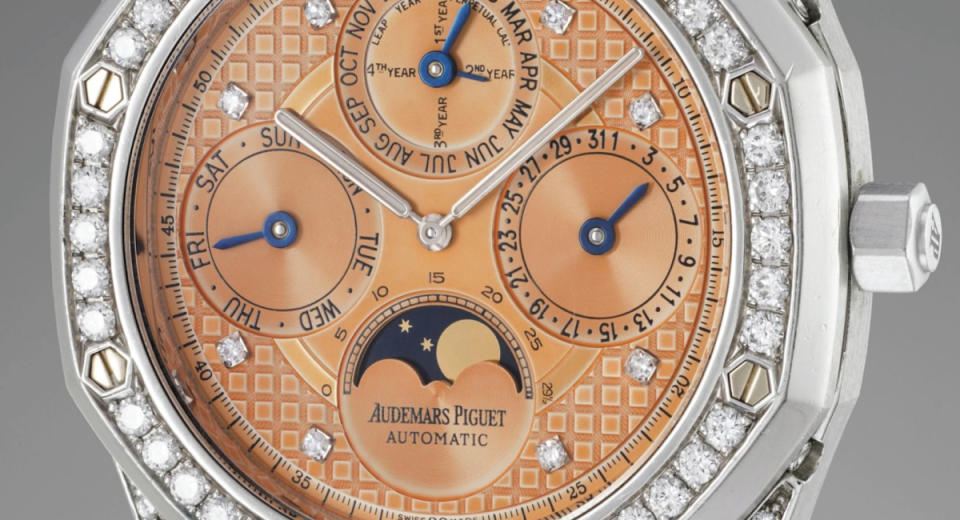

Ever since the recent trend for salmon dials kicked into high gear, we’ve seen just about every watch brand release a so-called salmon dial. However, in only a handful of high-end watches are these dials authentic salmon dials as I’ve described them above.

Arguing online over whether every vaguely pink-gold-colored dial under the sun is an authentic salmon dial or not seems to have become the new horological pastime. My friend over at Hodinkee, James Stacey, has thrown in the towel and started referring to any non-traditional pink-gold-colored dial as “salmon adjacent”—a strategy that exhibits James’s well-honed Canadian diplomacy, which I have adopted in more than one instance.

Trends being trends, many brands jump on the bandwagon as quickly as possible and use the term that will garner them the attention they’re grabbing at, which has been “salmon dial” for a few years now. But the number of ways that these salmon adjacent dials are made is varied and, alas, also confusing.

The ways to make a salmon-adjacent dial vary from enameling to lacquering to PVD coating and, perhaps most preciously, simply using solid gold dials that are then bead-blasted to achieve the “opaline” texture. It’s relatively easy to figure out which of these methods is being used: PVD will typically appear in inexpensive watches; lacquer will not achieve the texture of electroplated gold; enamel will typically be glossy (and brands will brag about having used this difficult process); and brands will certainly boast openly about solid gold dials.

‘Some Find the Name Unbecoming of a Beautiful and Expensive Watch’

To confirm my research into the elusive salmon dial, I hopped on the phone with the vintage watch expert Eric Wind of Wind Vintage. What was most interesting in our conversation was Eric relaying further confusion and opinions over salmon dials. My favorite among Eric’s tales was of clients who reject the term because, as Wind relayed it, “some find the name unbecoming of a beautiful and expensive watch.” I asked, “You mean the flesh of a stinky fish isn’t what one wants to think about when handling a rare Patek Philippe?” Eric laughed and said, “Yes, that’s the point.”

Having caught this notion, I can’t help but also turn up my nose at the term “salmon dial” and prefer following Patek Philippe in using the traditional term “gilded dial,” which turns out to be very lovely on the tongue, unoffensive to the nose, and—because “gilded” refers to a thin layer of gold—factual.

Best of Robb Report

Sign up for Robb Report's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.