A Brief History of Black Designers and Couture

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

As the lampshade millinery dripping in crystals, hot roller cloak and fridge facade finale dress adorned with magnets spelling out, “But who invented Black trauma?” slipped back into the Villa Lewaro estate to close out the historic Pyer Moss Couture show earlier this month, in came the reviews, the pronouncements, the questions.

Many noted Kerby Jean-Raymond as the first Black American designer to be invited to show a couture collection. Others asked, “What about Patrick Kelly?”

More from WWD

There are nuances to haute couture, to the Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture, and to the haute couture collections calendar that bear clearing up.

For starters, the French Fédération de la Haute Couture et de la Mode has three central bodies, or Chambres Syndicales: Haute couture, couturiers’ and fashion designers’ ready-to-wear, and men’s fashion.

Within the Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture, which oversees Paris’ Haute Couture Week, there are three categories of brands that can show: The 16 haute couture maisons that qualify for the designation (including Chanel, Dior and Givenchy); seven not-originally-Paris-based maisons (including Fendi, Valentino, and Iris Van Herpen), and a group of guests invited to show each season which, this time around, included Jean-Raymond’s Pyer Moss. The aim, at least in part, with the guest designers is to keep couture alive. Which also opens the storied art form to reinvention.

According to the Fédération, Jean-Raymond is, in fact, the first Black American designer invited to show as part the official couture calendar. Patrick Kelly, while he was the first American and first Black designer voted into the Chambre Syndicale du Prêt-à-Porter des Couturiers et des Créateurs de Mode in 1988, a different body within the Fédération, he never “officially” showed couture.

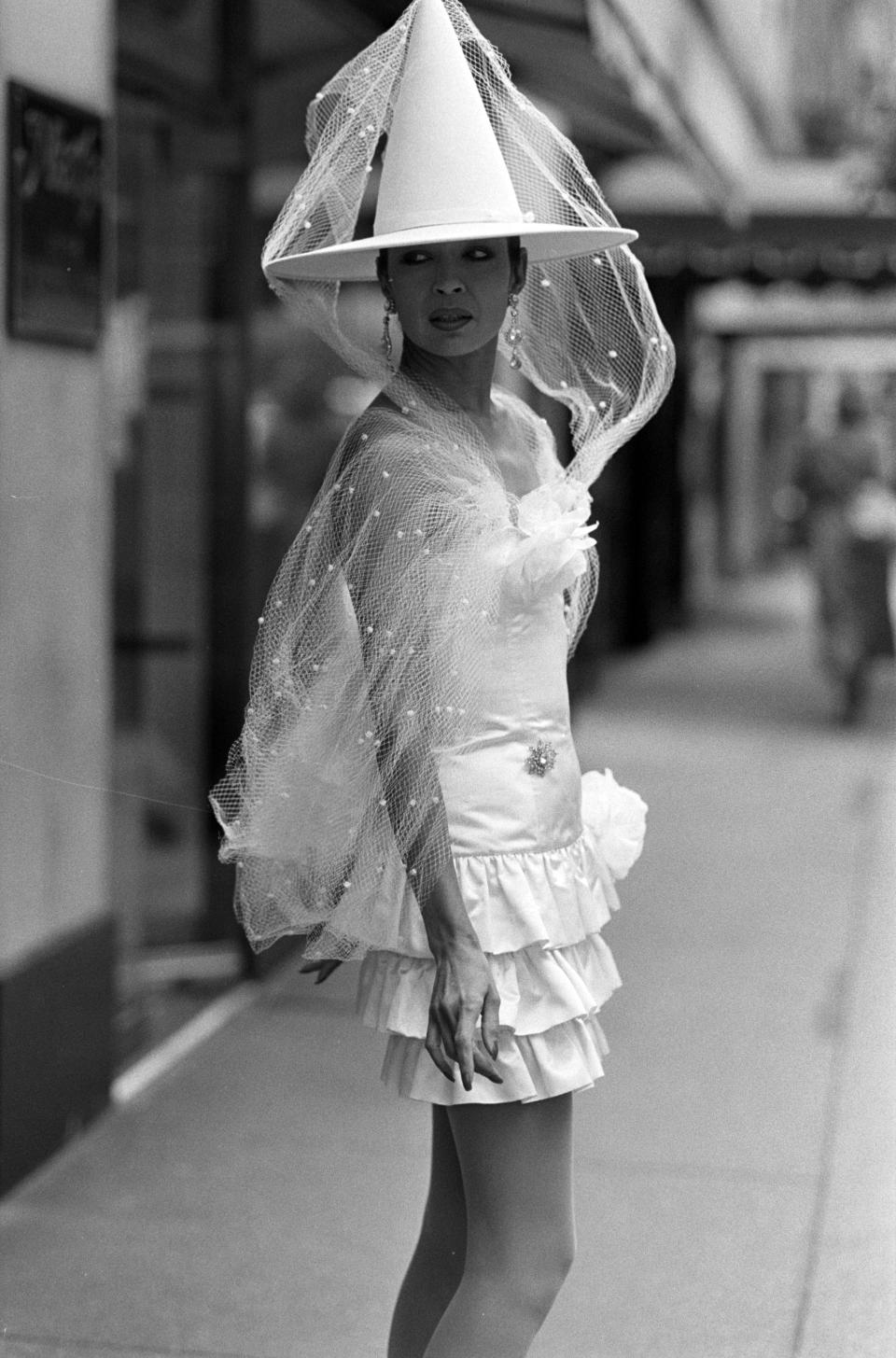

What the skillful and oft-undervalued designer did do was create a 65-piece couture collection that he called in a 1988 WWD article, a “wink at couture.”

WWD

“Lynn Manulis, president of Martha, Inc., found his couture show — including an orange and black houndstooth suit and orange-dyed lynx hat — so innocent and refreshing that she flew the collection to New York to sell in her boutique in September. The weekend stint drew a younger customer, Manulis says, and sales of about $80,000. The wedding dress was sold three times,” WWD wrote at the time.

While Kelly created and sold couture, doing so outside of the confines of the Chambre and its definitions and regulations meant, for all intents and purposes according to those at the upper echelons of fashion, it didn’t really count.

“Patrick Kelly produced high-end ready-to-wear, sort of following in the footsteps of Yves Saint Laurent at Rive Gauche, which was his model. He also did a couple of shows during the haute couture showings that he called ‘mock couture,’” Dilys Blum, the Jack M. and Annette Y. Friedland senior curator of costume and textiles at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, who curated the Patrick Kelly “Runway of Love” exhibit in 2014, told WWD. “They were outside the calendar, they weren’t officially sanctioned and he probably could have gotten in trouble for doing that, but they were small and those were made-to-order collections.”

Courtesy of Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2021

As Kelly’s “right-hand assistant,” Liz Goodrum was there when the designer was crafting his couture. And she still has some of the pieces in her personal storage.

“I didn’t know he called it ‘mock couture,’ but I know he did show it [in 1988]…It was a lot of long gowns and he felt very happy to be in the Chambre Syndicale and he wanted, eventually, to make couture gowns. But he did ‘mock couture’ because they were something similar to pret-a-porter, just more elaborate,” she said of the designer, who died in 1990. “At the time, your standards were a lot different than these new kids out here that call themselves haute couture people.”

Dispelling the discrepancies around whether Kelly was really the first to show couture, though, Goodrum said, “Patrick was more pret-a-porter, that’s the honest-to-god truth.”

Going back even further than Kelly, there was Jay Jaxon (né Eugene Jackson), who became “le premier couturier noir de Paris,” or the first Black American couturier in the Paris maisons. As Rachel Fenderson, fashion historian, curator and lead authority on Jay Jaxon, puts it, however, he has largely been “hidden in the fashion and historical narrative.”

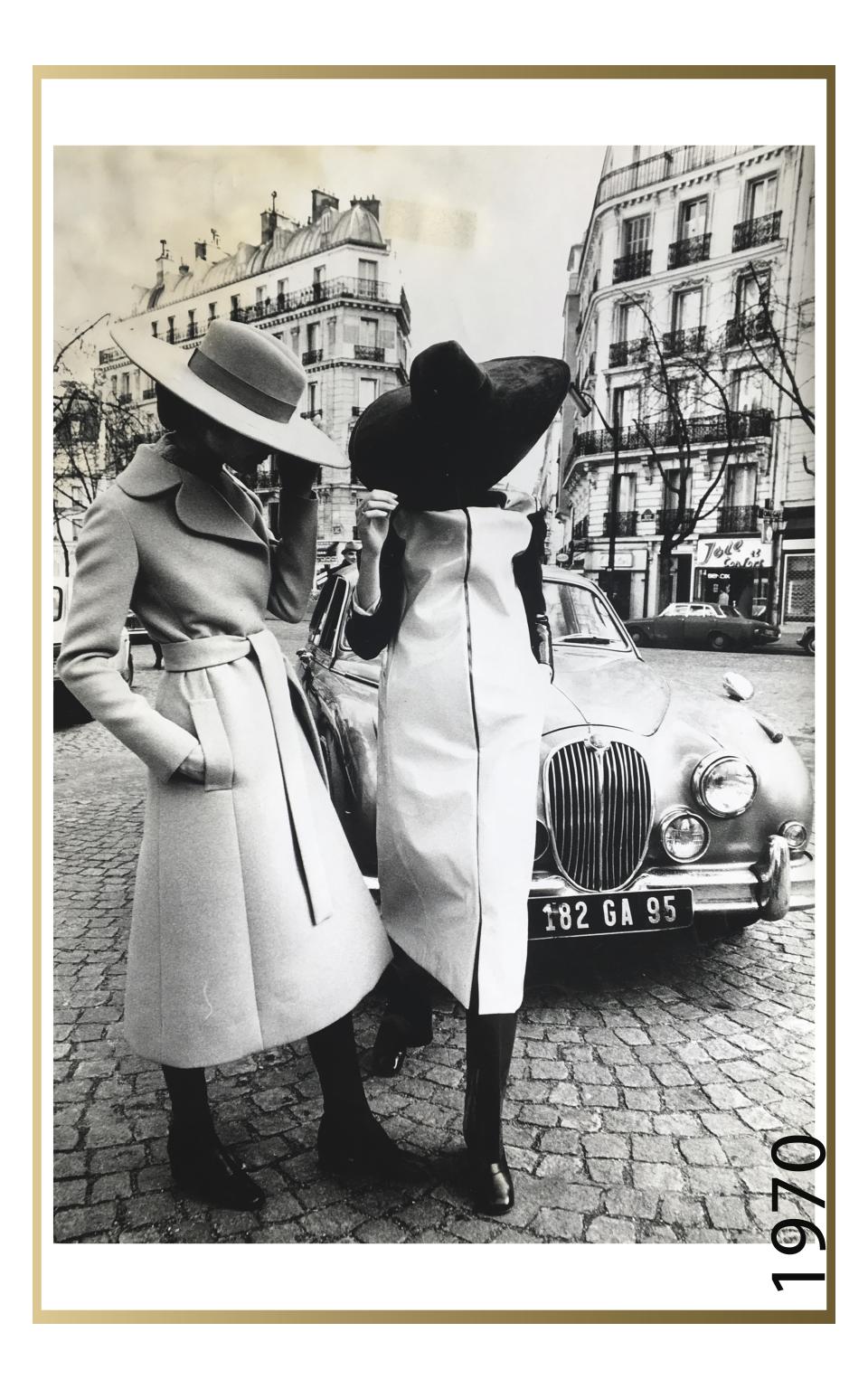

In 1970, the designer unveiled his first haute couture collection as head designer of Jean-Louis Scherrer (a couture house that eventually fell out of favor over back and forth financing and rights issues), according to Fenderson, and his career would include stints creating couture as an assistant designer at Yves Saint Laurent and as the direct assistant to Marc Bohan for Dior.

“We can think of him the same way we think of Olivier Rousteing for Balmain,” she said of that house’s creative director, who revived Balmain haute couture after a 16-year hiatus in spring 2019. “I think a large part of the reason why Jay Jaxon is not recognized is because of erasure.”

Photographer Unknown, Editorial Image, 1970, Maison of Jean-Louis Scherrer, Jay Jaxon’s Portfolio, Bequest of Lloyd Hardy, Rachel Fenderson Collection, 2017

Born in the same year as Emmett Till (1941) and descending on the design scene in Paris while America was in the midst of a civil rights movement and just two months before Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated (1968), Jaxon was ascending to the heights of fashion when there would have been many dissenters willing him not to.

“There’s so many different factors that play a role in his erasure and that…stems from the inception of slavery, it didn’t just start now,” said Fenderson, who is currently working on Jaxon’s biography to revive his legacy (the designer died in 2006). “This is something centuries in the making of how you can erase someone like Jay Jaxon, how you can quiet the voices of Stephen Burrows and Willi Smith.”

Or forgo mentions of Hylan Booker, who took the helm in 1968 as head designer of the House of Charles Frederick Worth, the maison whose founder is credited as “the father of haute couture.”

Today’s vernacular would say Black designers have been underrepresented in couture, but a more accurate descriptor might say they’ve been historically excluded from it. And where they have contributed, even that has been little acknowledged or credited.

“Oh they have contributed quite a bit [to couture] and there’s a lot of good designers out there that never even got any recognition,” Goodrum said. “That’s the same thing with a lot of the inventors.”

That erasure sat squarely at the heart of Jean-Raymond’s foray into fashion’s finest tier as he sought with each design — however contrary to traditional couture some deem it — to counter it.

His “Wat U Iz” collection, presented with more swagger than couture has likely ever seen, at the Irvington, N.Y., estate that once belonged to Madam C.J. Walker, the first self-made female millionaire in America, was more than looks to delight and adorn the wealthiest of wearers. Each piece was a tribute to Black innovators and their inventions that have been overlooked and undercelebrated in American history.

“It wasn’t necessarily about a review or execution or what people might have thought specifically about the actual pieces, I feel like [Jean-Raymond’s] work is bigger even than those commentaries, it’s bigger than those stories…Haute couture is very specific to Paris, France, it’s very specific to their culture, it’s very specific to the preservation of Frenchness and so I feel like it was bigger than that,” Fenderson said. “For [Jean-Raymond] to preserve the legacy of our people, which can often be erased and omitted from the historical narrative, in the physical form of haute couture pieces, I think it’s brilliant. That ideology, to place that within the space of…’not only am I a fashion designer, I’m going to be a historian, I’m also going to be a curator, you’re going to get this museum exhibition on this runway.’

“I think it’s bigger than what we can cultivate into words and into thoughts. I do think that it will take a few years to be able to really dissect and analyze [the Pyer Moss Couture 1] collection. I don’t think it’s a one-moment thing. I don’t think it’s a collection you look at once. I think it’s something you go back and revisit. I think you also revisit the artist and what the artist was saying. All of those things are intentional: the movement of the dancers, the de-robing of the dancers, then you also have the band and then what the band was playing, and the usage of all Black musicians. All of these things matter. He was telling a story…and creating the scenery and a moment that I think is way bigger than haute couture.”

What Jean-Raymond did, beyond shedding the shackles of couture’s prim and propriety, was sew Black imagination into the fabric of his message to highlight the culture — fashion was just the medium.

As Dapper Dan (less commonly known as Daniel Day) put it in an Instagram post celebrating the Pyer Moss Couture debut: “The ‘ESSENCE’ of fashion is the story your work tells, its [stet] your artistic voice for awareness. We don’t make garments, we make testaments.”

And, in addressing some less favorable reactions to Jean-Raymond’s efforts, Fenderson said, “Sometimes cultural things may not be up for understanding. It’s just the people who know, know.”

While it may not fall entirely to fashion to contend with the politics of race and how that has impacted those in the industry, designers determined to rise above it will continue to find new ways to recognize and represent their culture. And Jean-Raymond was one among those making space for Black designers in conversations around couture.

“Before there was Kerby Jean-Raymond for Pyer Moss in 2021, Robyn Rihanna Fenty for Fenty in 2019, Virgil Abloh for Louis Vuitton in 2018, Olivier Rousteing for Balmain in 2011, Ozwald Boateng for Givenchy in 2003, Chambre Syndical [du Prêt-à-Porter des Couturiers et des Créateurs de Mode] member Patrick Kelly in 1988, there was Jay Jaxon for Jean-Louis Scherrer in 1969,” Fenderson said. “They didn’t all design couture but they all made space… And what I mean by making space is that they broke down barriers, they opened doors and they left those open for more to follow. They made it easier for us to be there and…not easier in terms of technique and skillset, easier in terms of our presence…And for us to be able to have an experience that’s more suitable for intellectual output and what we can develop versus our skin color.”

Jean-Raymond put representation at the center of couture, and it’s a conversation fashion must contend with at all levels as it faces its own inherent erasure, the kind that leaves a few designers exalted and others unremembered. The same kind that left some inventors praised in the history books and others pushed aside.

Elaine Brown, American activist and the only woman leader of the Black Panther Party, opened the Pyer Moss Couture show asking — in a nod to Dr. Martin Luther King’s 1967 address to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference Convention in Atlanta — “Where do we go from here?”

Now that fashion has seen a new type of message, one that spoke to more than craft and custom fits, articulated through its haute creations, it may be worth considering: Where does couture go from here?

Best of WWD

Sign up for WWD's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.