A Bridge for Max

This article originally appeared on Trail Runner

Max LeNail was five minutes away from the end of his run when the hail storm started. He had already summited the South Fortuna peak in San Diego, California's Mission Trails Park, a relatively easy trail run that was part of his training for the Dipsea Race in the Marin Headlands north of San Francisco.

When the hail came, it was unlike any hail storm the San Diego region had ever seen. LeNail kept going, following the San Diego River Crossing trail, which he thought would lead him back to his warm and dry car in the parking lot. But instead, he came across a rushing river and no bridge.

No one knows exactly what happened next.

RELATED: Meet the Rucky Chucky Raft Crew of Western States 100

LeNail's GPS data from his Garmin shows that he hesitated at the side of the river, then decided to cross it, likely wading into what is usually a very small stream in the summer, but what was swollen that January morning in 2021.

The next day, LeNail was found dead further downstream. He was almost 22, about to graduate from Brown University, with a premed concentration and plans to become a doctor.

His death was a tragedy for everyone who knew him--parents, friends, outdoor enthusiasts, even strangers across the San Diego region. It also led to his family taking immediate action to fix a problem that could have saved his life: building a bridge across the river. Two years later, they're still fighting for that bridge.

"He Found Joy in Everything"

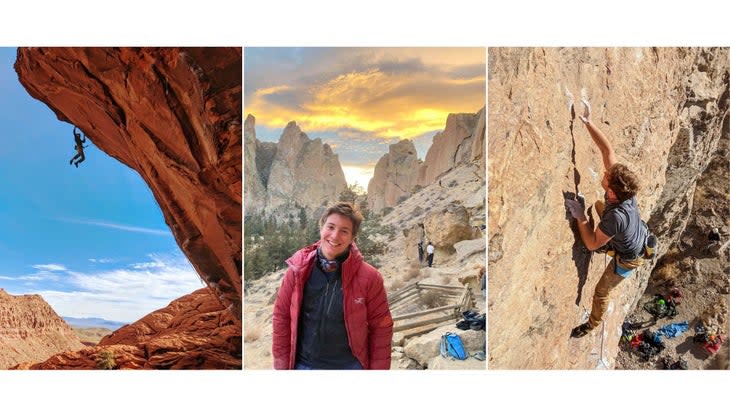

Max LeNail's father, Ben LeNail, says his son was always athletic. He played soccer, ultimate frisbee, and was a great runner, cyclist. He also became a world-class rock climber during high school and college. One of his closest friends, Shannon Murphy, joined Max LeNail on many of his rock climbing expeditions, and says that he had a very rare combination of being focused and determined about a challenge, but never intense.

"He found joy in everything, even when it was something that he clearly cared about achieving, But he never let that take over the joy of it, which I think was one of the really beautiful things about climbing with him," she says.

LeNail would train intensely, going to sleep early and waking up early and doing yoga and eating right, she says. "But when we were actually climbing and he would fall, he didn't care," she says. "He was just like, 'oh, that was really fun.'"

LeNail was studying at Brown in 2019 when COVID struck and the campus closed. He and a group of friends made an adventure pod, where they lived in different outdoor meccas, from Lake Tahoe, California, to Bend, Oregon, and took remote classes and spent their free time outdoors. They had just relocated to San Diego and LeNail discovered Mission Trails Regional Park, an 8,000-acre urban park with more than 60 miles of trails, perfect for his ultra training.

When Trails Turn into Rivers

On Jan. 29, 2021, Max started his run around 10:30 A.M., and he ran alone, something very common in the well-traveled Mission Trails. By 12:05 P.M., he was at the top of the 1,100-foot South Fortuna Mountain and recorded a video on his phone.

"It's a moody day," he said, showing the gathering clouds. "Hopefully it's not too cold."

By late afternoon, Max LeNail's roommates started worrying because he wasn't home. They called him and got no answer. Then they drove to Mission Trails, saw his car in the parking lot, and instantly knew something bad had happened. They called the police, who sent a helicopter, but by that time it was 7 P.M. and dark. The police sent a helicopter with night vision, but couldn't find him.

Max LeNail's roommates called his parents, and Ben LeNail says they stayed up all night organizing a search and rescue.

"It went totally viral. Boy Scouts, trail runners, mountain bikers, churches, volunteers of all kinds, and 800 people showed up," Max's father Ben LeNail says. Max's mother Laurie Yoler traveled from their home in Palo Alto to San Diego to help direct the search.

Max's body was found at noon the next day. The autopsy showed he didn't have any trauma, so it's unlikely that he hit his head, but was instead likely sucked in a current in the river and possibly suffered hypothermia, Ben LeNail says.

When Grief Turns into Action

"We're absolutely petrified with grief. Within a day or two, we thought this could totally destroy us, and we could be broken forever," Ben LeNail says about the loss of his son. "We could become ghosts, or we can decide not to be like that. We were very messed up, but quickly we thought, we want to be outward facing instead of people who turn inward and shut down and become completely sealed. We want to be in the world and be turned towards others."

Within a day, the LeNails knew what they wanted to do. They were hearing from hundreds of people who had the same question.

"Everybody said, 'it's insane, why isn't there a bridge there?' It is one of the most popular trails in the park, and it's intersected by the river," Ben LeNail says. "Why are people exposed to this danger? There absolutely should be a bridge there."

And so, they decided to build a bridge over the river and name it after Max.

Research led them to a frustrating discovery: the proposal for a pedestrian bridge at the place where their son died had been part of the Mission Trails master plan for a decade.

"There was total apathy in terms of, 'we don't have enough money,'" he says. "And frankly, I think they needed the impetus of a death, an accident, to really mobilize people and say, 'look, we need this bridge, and we need it sooner than later.'"

A depth marker now stands in the middle of the river to show potential crossers how high the water is. But even in the winter, when the water can be four or five feet high, people cross. Many will take off their socks and shoes and wade through on a rocky, slippery spot close by.

"There was always a sense that people will cross, people will slip, and people will struggle, but nobody has come to any serious harm thus far, and we [the park administration] can kind of drag it along a little bit longer," Ben LeNail says. "Max's death was the impetus, and our absolutely fierce advocacy that we are not going to let go. We are going to be there advocating for the bridge and in their faces and would not drop it."

Building Bridges

Within a few weeks, the LeNails reached out to elected officials and the Mission Trails Regional Park Foundation. Everyone agreed a bridge should finally be built. But now, it's been more than two years after Max LeNail's death and construction has not begun.

The target is to finish the bridge and hold an inauguration for it in 2024. But there's a long way to go to get there.

LeNail says they are still wading through the city bureaucracy to get the required surveys and permits done. They still have to do environmental impact studies to be sure the ground is secure and that wildlife won't be disturbed. Once construction begins, it could only take three months to build the bridge.

San Diego City Councilmember Raul Campillo represents the area and chairs the Mission Trails Regional Park task force, and he says there is always a list of projects in the park that need to be completed, and never enough money to do all of them.

"So the bridge had not been built, but things like the visitor center had been built, trail preservation had been built, markers for hikers, lots of different things like that had been built, but the bridge itself had not," he says. "It is one of the higher-priced items, and it requires a lot of engineering, permitting, scientific research, and analysis. And so up to that point, it had just not been prioritized like things that many other hikers and trail goers use in the park on a daily basis. I would say that we're well within a standard deviation of time to build this type of project," he says.

Campillo says it's not unusual for a project like this--a bridge over a river in an environmentally sensitive area--to take this long.

Many San Diegans, including Jennifer Morrissey, executive director of the Mission Trails Regional Park Foundation, are blown away by the fact that the LeNails have dedicated themselves to something so fully during a time of unimaginable grief.

"They've channeled this tragic event into positive action, building a bridge in Max's memory that can provide safe passage for park users for generations to come," Morrissey says.

In early 2023, the park built a bench near the place where Max died with his name emblazoned on the front.

"This is a way for people to go and reflect and also where they can see the project, the process of construction when it's happening," Morrissey says. "And then eventually one could sit on Max's bench and be looking at the bridge."

In July, LeNail visited San Diego again to put pressure on officials. He says he's extremely persistent, a self-described "pit bull," meaning there's no way he's going to allow the bridge to not be built. He spends time every week, working on this project that is outside his normal job as a biotech consultant, and every day he thinks about his son and works to get the project done in his honor.

"He'd be pleasantly surprised, but I think he would be enchanted," Ben LeNail says of what Max would think about this work. "He would love to have generations of athletes and outdoors people use the bridge."

The bridge will be made of prefabricated steel, and so it will be built to last. That means in 100 years, people will walk on the bridge and remember Max, LeNail says.

Follow updates on the progress of the bridge's construction here.

For exclusive access to all of our fitness, gear, adventure, and travel stories, plus discounts on trips, events, and gear, sign up for Outside+ today.