A New Box Set Unearths Acetone, the Greatest ’90s Rock Band You've (Probably) Never Heard

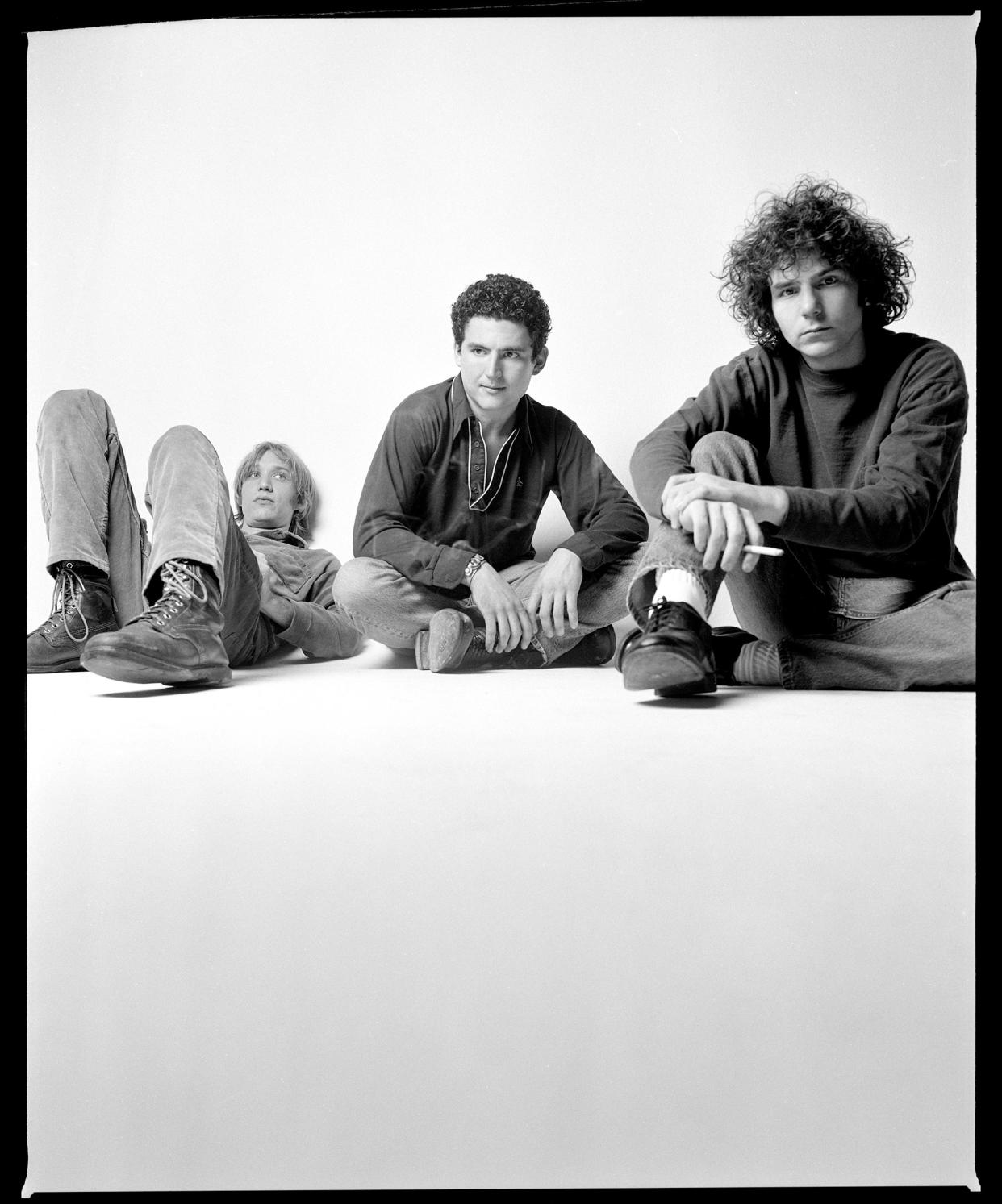

Photo by Chris Cuffaro

Mark Lightcap, the guitarist for Acetone, greets me outside a pub in Sierra Madre, California. Nestled in the foothills of the towering San Gabriel Mountains, it’s a small town just a short drive from downtown Los Angeles, but with its rows of Queen Anne Victorian houses and pine-scented air, it feels a universe away. Lightcap, 57, sports a swirling mop of curly salt-and-pepper locks, the same hairstyle pioneered by Zeus. “This pub is a little loud,” he says. “Let’s chat at my house.” I drive and Lightcap walks his bike, which has a flat. Minutes later and a few blocks away, we convene in his backyard to discuss his old band and the new Acetone box set over canned IPAs.

When I pose the question, “You ever listen to Acetone?” to my record-collector friends, the answers I receive range from “Not really” to “My college radio station had one of their CDs” to “The paint thinner?” to “Holy shit, they rule.” They’re the equivalent of a secret handshake — if you know, you know. The box set, I’m still waiting., released this week by New West Records, consists of 11 LPs, including the band’s entire studio output alongside unreleased material, and a 60-page book with essays by J Spaceman of Spiritualized and Drew Daniel of Matmos. It’s a comprehensive and stunning experience that preaches to the unconverted masses: this is a band that deserves to be heard.

When asked about Acetone, Colin Meloy of the Decemberists, a fan of the band since his days as a college student in Missoula, Montana, tells me, “Mark Lightcap is legit a guitar god.” The box set, with its wealth of indelible songs, and the band’s devoted cult following raise the questions: Why did Acetone go unnoticed in the ‘90s? And why do we, the crate diggers and music freaks, seek out and obsess over bands that slipped through the cracks?

****

In his backyard, Lightcap moves a hacksaw and assorted tools off a patio table and we take a seat. His dog, Gretel, a 12-year-old Australian Kelpie, sidles up to me, and I scratch her behind the ears. “It’s been amazing,” Lightcap says of the period leading up to the box set’s release. “We were—I don't want to say a miserable failure, but Acetone just didn't sell any records in the ‘90s. It's incredible to me that our stuff has stuck. It's always had this cult audience. For some reason now, there are more people coming around to it. It’s incredibly gratifying.”

Acetone, formed in northeast Los Angeles from 1992, were an underground band that critics occasionally (and somewhat inaccurately) lumped into the then-nascent “slowcore” movement. With Lightcap on guitar, Steve Hadley on drums and Richie Lee on bass and vocals, the band created songs that could shimmer like the sun-soaked waves at Zuma or rumble and slither like a Topanga Canyon mudslide. Listening to Acetone often feels like eavesdropping on a conversation between Lightcap’s graceful and sinuous guitar work and Lee’s floaty bass lines. Hadley’s lithe grooves hold the whole enterprise together. Like Tom Verlaine and Richard Lloyd in Television before them, Lightcap and Lee’s instruments seem to be speaking to each other in a language of their own invention.

After a bidding war landed Acetone a healthy advance, the band went on to release four studio albums — 1993’s Cindy, 1996’s If You Only Knew, 1997’s Acetone and York Blvd. in 2000 — but none of them made a dent at the cash register. Their first two LPs were released by Vernon Yard Records, the latter two by Neil Young’s Vapor Records. “At a certain point,” Lightcap says, cracking open a beer, “we became accustomed to the idea that we were never going to sell any records, but we were just going to keep doing it.”

After failing to make a splash on the charts, Acetone came to a tragic end in 2001 when Lee, then 34, died by suicide. Their albums eventually went out of print. The band seemed destined for the dustbin of history. Then, at the same glacial pace as the slinkiest of their songs, legends and lore began to grow. In 2017, Light in the Attic, the independent label known for resuscitating the discographies of influential but little-known musicians, released an Acetone compilation bluntly titled 1992-2001, a 16-song collection that gave a new generation of listeners an enchanting, hypnotic glimpse of what the band once was.

Light in the Attic’s retrospective was released in tandem with a “nonfiction novel” about the band, Hadley Lee Lightcap by Sam Sweet. It’s a music biography, a cultural study of Los Angeles, and an epic tragedy with a pinch of art crit—the kind of rock journalism that makes rock journalists gush in hyperbole. Sweet plays Boswell to Acetone’s Samuel Johnson and weaves an elegantly written tale of two CalArts freaks (Lightcap and Lee) teaming up with a SoCal surfer (Hadley) to create music. At the moment, Sweet’s book is difficult to find (I borrowed a copy from a friend), which only adds to the band’s mystique. “It's joined the Acetone conga line of obscurity,” Lightcap says.

If the 1992-2001 retrospective was one tile of a mosaic, the box set is the band in widescreen Technicolor. “I think the box set is kind of a revelation,” Meloy says. “It’s fascinating to be able to see the arc of the band, from their beginning to the end. All that brash guitar stuff in the first records giving way to that lazy, opioid jamming.” Listening to the lush guitar tones, Lee’s fragile voice and Hadley’s soulful beats on the reissues, it makes sense that they were drowned out by a deluge of sludgy alt-rock. On dulcet songs like “Germs” or “Louise,” Acetone sounds far more contemporary today than they did in the ‘90s.

****

Documentarians love to make movies about bands and musicians who escaped the notice of the record-buying public, like A Band Called Death, Searching for Sugar Man and Big Star: Nothing Can Hurt Me. These docs ask the question: Why did we overlook these generational talents? In the strange case of Acetone, Lightcap has a theory.

“With us, it’s like a self-fulfilling prophecy,” he says. “If you go and look through my record collection, my favorite records are the ones where I feel like I’m the only one who has it.” I think there’s more to it than that. When bandmates find each other, like Hadley, Lee and Lightcap did, it can be a cosmic event, as illustrated in Sam Sweet’s book. When a listener finds that band and their songs, it’s cosmic just the same. As listeners, we’re always chasing that phenomenon.

After the end of Acetone, Lightcap took a job as a fabricator in celebrated Los Angeles visual artist (and fellow CalArts graduate) Mike Kelley’s studio. After Kelley’s suicide in 2012, Lightcap transitioned to work as the collections manager for Kelley’s body of work. He currently plays guitar in The Dick Slessig Combo, a band even more obscure than Acetone by design.

I ask Lightcap if, in the ‘90s, they felt like the public were idiots for not latching onto their albums, or if they thought that Acetone was the problem. “I would say both,” he says. “We were disgruntled, and we did think people were idiots. But there was also this sense of, are we doing something wrong? Is it us?”

As Gretel, the Australian Kelpie, playfully nibbles on my hand to encourage me to keep scratching behind her ear, Lightcap cautions against mythmaking with obscure bands. “You have to be aware that oftentimes there’s a false narrative superimposed on bands after the fact,” he says. “Look at Death. Death is an amazing band, but that whole narrative of these guys invented punk rock? It's like, well, no—they're just freaks who had this incredible band that slipped through the cracks. It's enough for them to have just been amazing.” His description of Death could easily be applied to Acetone.

****

As our beer cans get lighter and the November sun sets early, Lightcap and I continue talking in total darkness. He warns that we “might get strafed by an owl.” I ask Lightcap if, when assembling the box set, he’d catch himself thinking about what Lee would’ve made of the spotlight finally landing on Acetone.

“He would've loved it,” Lightcap says, raising his voice slightly to compete with the chorus of crickets that start chirping around us. “There's no way to work with this material and not be thinking of him constantly. He would be totally gratified and stoked, along with the rest of us. I mean, Richie, he wanted to be a fucking rock star. When he took his life, he definitely didn't want to pull the music down into the grave with him. He wanted to live on. So he would be totally excited about all of this. He was our number-one cheerleader. Richie was like, ‘We are the best band in the world.’ And Steve and I would be like, ‘Dude, come on. We fucking kick ass. But you're going a little far.’ He insisted: We are the greatest thing. But, yeah, I listen to this stuff and I miss him.”

It’s so dark outside that Lightcap considers getting his Coleman lantern, but he doesn’t. I ask if he’s thought about the fact that, with the box set and the reissued LPs, the Acetone narrative is about to open a new chapter. In 2017, when Acetone played a show in Los Angeles with Hope Sandoval of Mazzy Star on vocals, it was their first in fifteen years; Lightcap says that he and Hadley may play live as Acetone again soon. For years, Acetone records were a rare commodity and sold for hundreds of dollars. Now, they’ll be available to anyone who wants them. Lightcap laughs. “I’m okay with that,” he says. “We’ve done our time in the black hole.”

Originally Appeared on GQ