This New Boutique Hotel in Havana Is a Dream Destination for Art Lovers — Here’s What It’s Like to Stay There

Plus, there are still daily flights from the U.S. to Cuba — check out our primer at the bottom of this article.

Nestor Kim/Courtesy of Tribe Caribe

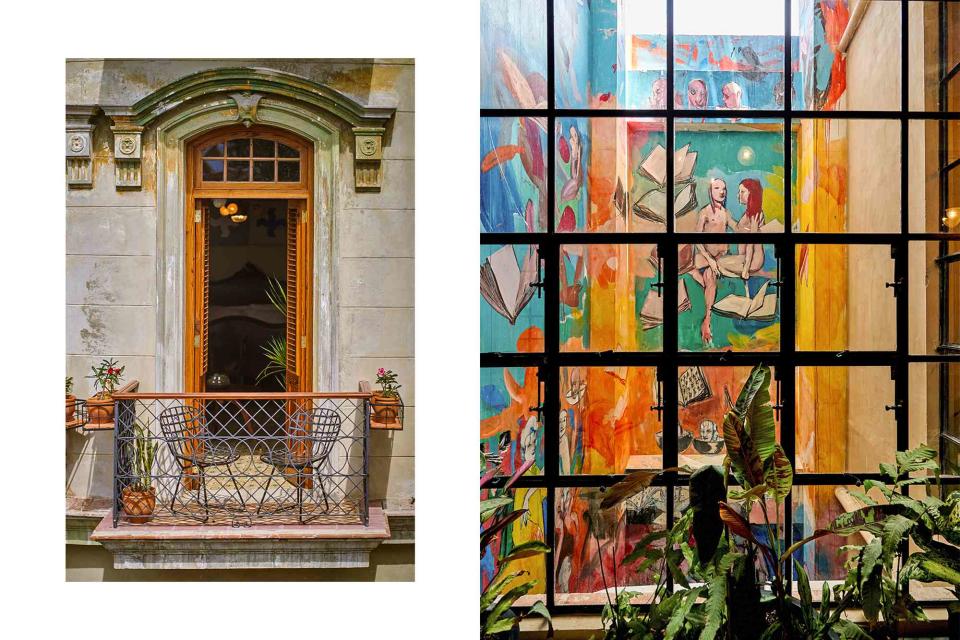

From left: A guest-room balcony at Tribe Caribe, in Havana's Cayo Hueso district; Cuban artist Carlos Quintana's mural in a courtyard at the hotel.When Tribe Caribe opened its doors in the Cayo Hueso district of central Havana last winter, it celebrated not with a formal inauguration or bottles of Champagne but with a block party. All evening, neighborhood kids lined up outside the boutique hotel to get their faces painted, while bands, DJs, and dance troupes drew a crowd of hundreds.

Cayo Hueso residents wandered through the 11-room hotel’s ground-floor gallery, the Black Box, where an exhibition by Cuban artist Juan Carlos Alóm included videos of local streetscapes as well as photographs of the building’s restoration. “People had been wondering what was going on in here, and when they saw these images of their own neighborhood and of themselves — people cried,” said Andrés Levin, the musician and record producer who founded Tribe Caribe with his business partner, Chris Cornell. “There are just so many stories to tell about this place.”

Nestor Kim/Courtesy of Tribe Caribe

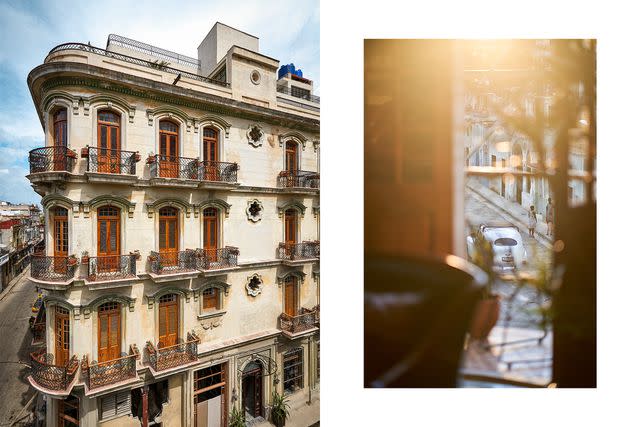

From left: The 1930 building that is home to Tribe Caribe; a view of Cayo Hueso from a third-floor suite.Before it became a luxury hotel, the 1930 building had fallen on hard times. Salty air blowing off the Caribbean Sea, just a few blocks away, had rusted its iron balconies, and the interior had been subdivided into eight apartments. The architect behind the restoration, Orlando Inclán, said the building was just a few years away from total collapse. With its façade restored, but its 100-year patina left intact, Tribe Caribe does more than connect guests to Cayo Hueso and greater Havana; it serves as a creative hub with music and community at its core.

The economic devastation of the pandemic set off widespread protests in 2021 and sparked the largest exodus of Cubans since the 1959 revolution. As the artist José Manuel Mesias told me one evening at Tribe Caribe’s rooftop bar and restaurant, “It feels like half the country has left.” Levin later told me that the quartet playing in the bar, which was made up of some of the city’s most accomplished jazz musicians, often plays under the name Los Que Quedan (“Those Who Remain”).

For at least the past century, working-class Cayo Hueso has played a central role in Havana’s musical history. Levin told me that it was in Parque Trillo, a block from Tribe’s front door, that the legendary vocalist Benny Moré first sang with the percussionist Chano Pozo — the man who introduced the sounds of rumba to the lexicon of American jazz in the 1940s. In 1970, the neighborhood luminary Juan Formell founded the band Los Van Van, which was central to the development of Cuban popular music. When Tribe brought the present-day iteration of Los Van Van to play a free concert in Parque Trillo as part of Havana’s Jazz Fest in January, some 2,000 people showed up; many had never had a chance to see the band live.

Nestor Kim/Courtesy of Tribe Caribe

A spread of Spanish tortilla, tacos, salad, and fruit at Manteca, the hotel's restaurant.By the time Levin first visited Cuba in 1998 (now based in Havana, he lived, at the time, in New York City), Cayo Hueso’s glory days were in the past — just one of countless victims of Cuba’s economic tailspin of the 1990s. The 2010s saw a brief reprieve when domestic reform allowed small businesses to function more easily and, later, when President Obama loosened travel restrictions for Americans. But after Donald Trump entered office, he limited the amount of money U.S.-based Cubans could send home — an essential economic lifeline. He also scared off potential travelers by banning U.S. cruise ships and discontinuing the “people-to-people” travel license many Americans had used to visit the island.

The artists and musicians who remain are Tribe Caribe’s lifeblood, just as they are Havana’s. The young, enthusiastic staff, most of whom are new to hospitality, nearly all hail from Cayo Hueso or nearby districts and approach the project with an infectious warmth and spontaneity. The restoration, too, relied on local talent — from the Havana-based Inclán, the lead architect, to the metalworkers who remade the building’s balconies and the carpenters who restored the Art Deco and colonial-style furniture that Cornell had spent years collecting from local antiquarians.

Rather than leaving the building as an homage to the past, Levin and Cornell brought in Sachie Hernandez, curator for the independent Havana art collective La Sindical, to turn Tribe Caribe’s public spaces and guest rooms into galleries. Sensuous landscapes by Maikel Sotomayor and explosive neo-Expressionist paintings by Ángel Ricardo Ríos share space with photographs by Michel Pou Díaz and Alejandro González — works that address issues like queerness and migration with touching, and sometimes surprising, specificity.

Nestor Kim/Courtesy of Tribe Caribe

Commissioned artworks on display in a junior suite.Tribe Caribe’s commitment to the city’s creativity extends well beyond the its doors. In the course of a few days, the hotel arranged for me to visit a workshop for dance troupes in a former mirror factory, and I spent hours at artists’ studios, talking candidly about Havana’s history and the joys and difficulties of working there. I spent one evening at an intimate outdoor concert and another learning about rumba from one of Cayo Hueso’s most illustrious musical families. One boiling afternoon, I waded into the cyan Caribbean Sea at Tribe’s 1950s beach house, a 25-minute drive away on the coast. I returned to the city for dinner at Grados, where chef Raulito Bazuk, working from the kitchen of his childhood home, prepared a relaxed tasting menu using the limited ingredients available on the island: locavorism refracted through a political lens. “I want people to enjoy themselves, but I don’t want to create an ‘oasis’ or a ‘bubble,’ ” he told me before I sat down to eat. “I want to open the door to a conversation.”

For all its aesthetic appeal, Tribe Caribe is, at its core, about facilitating these sometimes challenging, often joyful, always illuminating experiences in a city that is all too easily — and all too often — reduced to a romantic stage set. More than its crumbling mansions and fortifications, Havana is, like cities everywhere, a product of its people, the ones who remain, the ones who have gone, and the ones who may yet return.

Nestor Kim/Courtesy of Tribe Caribe

Vintage furnishings in a guest room at Tribe Caribe hotel.How to Visit Cuba

In August 2016, JetBlue flew from Fort Lauderdale, Florida, to Santa Clara, Cuba — the first commercial passenger flight between the two countries in more than half a century. Since then, the U.S. government’s stance on travel to Cuba has, at least rhetorically, tended to fluctuate, but those flights have never stopped. “The big misconception is that President Trump made travel to Cuba illegal, which he didn’t,” says Molly Layman of the Miami-based travel agency Cuba Candela. “We always emphasize that travel is easy and safe.”

Currently there are 10 daily flights to Cuba from Miami, as well as daily flights from Fort Lauderdale, Houston, Newark, and Tampa. When purchasing flights online, you’ll be asked to select your reason for travel. President Biden reinstated the people-to-people travel license in 2022; this is the category most often used by tour groups. Selecting “Support for the Cuban People” allows for virtually unrestricted individual travel. Visas are available for purchase at any airport that offers direct flights to Cuba, usually at check-in, but tour agencies like Cuba Candela (as well as Tribe Caribe’s in-house travel coordinators) can arrange for visas to be sent by mail ahead of time.

Customs officers in the U.S. might, though probably won’t, ask to see an itinerary for your visit, and carrying a hard copy is advisable. But practically any activity that engages with local businesses — eating at a private restaurant, visiting artists’ studios, attending a concert (in a non-state-run venue, of course) — counts. The use of American credit and debit cards remains restricted, but many businesses accept U.S. dollars. Layman suggests arriving with about $100 per day in cash. If you want Cuban pesos on hand, it’s best to change dollars at your hotel rather than at the airport.

Leave generous tips where you can, and avoid haggling. The Cuban economy remains fragile — in no small part because of the ongoing U.S. trade embargo — and visitors are, for many families, a lifeline.

A version of this story first appeared in the November 2023 issue of Travel + Leisure under the headline "Heart of Havana."

For more Travel & Leisure news, make sure to sign up for our newsletter!

Read the original article on Travel & Leisure.