Boundary-breaking Photographer William Klein Dies at 96

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The multidisciplinary artist William Klein, who mastered photography with an unequivocal precision, has died at the age of 96.

The American-born Klein died Sept. 10 in Paris, where he had lived for most of his adult life. The ICP’s managing director of programming David Campany, who curated the retrospective of Klein’s work that is on view at the ICP in New York through Thursday, confirmed his death on Monday.

More from WWD

Fashion photography, street photography, painting, filmmaking, graphic design, abstract art, writing and book making were among the mediums that Klein excelled in during a 70-year plus career. Inventive and unconventional in his pursuits, Klein’s resounding sense for human nature and quest for the unexplored led to a body of work that crossed mediums. Whether working on commercial projects or personal ones, Klein blended his New York-grown street smarts with an appreciation for European avant garde artists.

During his New York days, Klein frequented the Museum of Modern Art, where he discovered the work of photographer Edward Weston, as well as documentary ones of the ’30s like Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange — all of whom influenced him.

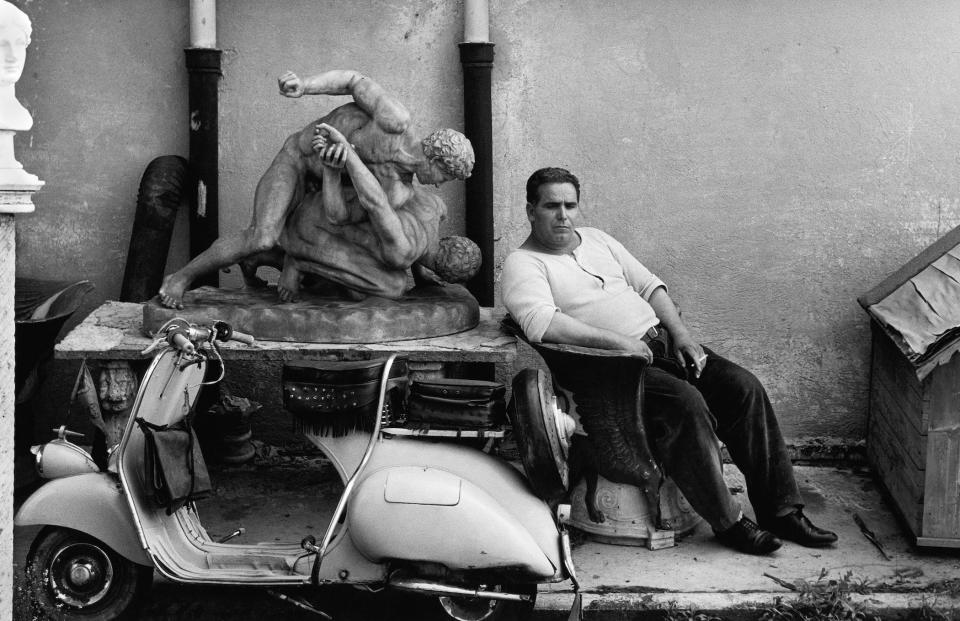

Paul Martineau, curator at the J. Paul Getty Museum, said Monday, “William Klein revolutionized fashion photography during the late 1950s and early 1960s. Not by taking it out of the studio, which had been done previously, but by dynamically juxtaposing female pulchritude with gritty urban environments (think New York, Paris, Rome). Klein’s fashion pictures were extremely compelling because they addressed the rapidly changing roles of women with empathy, wit and style.”

Klein once said of his own work, “I came from the outside, the rules of photography didn’t interest me. There were things you could do with a camera that you couldn’t do with any other medium — grain, contrast, blur, cock-eyed framing, eliminating or exaggerating gray tones and so on. I thought it would be good to show what’s possible, to say that this is as valid of a way of using the camera as conventional approaches.”

In a written tribute, Campany noted how Klein embarked on a two-year stint in Germany in 1946 as part of an Allied forces reconstruction mission. There, he worked as a radio operator — on horseback.

“His creative life began as a painter in post-war Paris, the city that remained his home. On the first day there, he asked a young woman for directions to the Sorbonne, where he was to take some classes. The woman was Jeanne Florin. They were soon married and [stayed] together until her death in 2005,” Campany wrote. “Klein also enrolled at the studio of the great artist Fernand Léger. He progressed swiftly from figurative work to abstraction, and from canvas to the photographic darkroom. His striking abstract photographs appeared on the covers of design magazines such as Domus, as well as books and music LPs.”

After befriending the abstract artist Robert Motherwell in Paris, they discussed scale, the relation to art within the space that it hangs. Later inspired by the Bauhaus and Mondrian movements, Klein made murals, and collaborated with Angelo Mangiarotti. The Bauhaus’ mixture of art and design and their willingness to experiment enormously influenced Klein.

Over time, he became more widely recognized in the mid-’50s for his fashion and street photography. A born-and-bred New Yorker, he spent most of his life in Paris “because there is a lot less bulls–t,” he told WWD in 2013. There, in a strange twist of irony, he won the Prix Nadar in 1957 for “New York,” a book of photographs taken during a brief return to his hometown in 1954.

Similar titles followed, including “Moscow” (which was done during the Cold War), “Rome” and “Tokyo.”

Much of what the Jewish photographer experienced decades ago, including anti-Semitism, and subjects that he explored, like the uproar with Russia, still permeate today. Such relevance was Campany’s motivation for the ICP show. Campany explained in June, “I’m not interested in Klein just as a historical figure. I’m interested in how he speaks to the present and his continued influence on younger photographers and filmmakers. There’s almost no area that hasn’t been touched by his work.”

Klein spoke of his affinity for France in that interview, “Paris is a place where a lot of things have been done on every level and there is less the atmosphere of ‘Ooh la, la, look at us.’ I grew up on 109th Street [in Manhattan]. My father was like Willy Loman in ‘Death of a Salesman.’ He was convinced that New York is the center of the world and America is the land of opportunity. He didn’t have much opportunity or maybe he did but he never really made much of it.”

In 1954, Klein embarked on a fashion career, after he was invited by Vogue’s then-esteemed art director Alexander Liberman to join the magazine back in New York. “Klein had no experience at all of fashion but Liberman saw in him an incomparably strong vision, a hunger to experiment, and an uncanny knack for visual problem solving,” Campany said.

Photographer Gideon Lewin recalled Monday meeting Klein briefly in Paris in the late 1960s, when Lewin was working for Richard Avedon. “He was one of the great photographers I took notice of. He was always experimenting, rarely following the conventional standards of photography,” Lewin said. “He experimented with motion and painting with light some of his fashion images, a technique that Hiro perfected in later years.”

Lewin and his fashion designer wife Joanna Mastroianni keep one of Klein’s photographs on a wall in their bedroom, “Dorothy and Light Gun, Paris 1962 Vogue.” Lewin described Klein’s images as full of texture that offer “a glimpse of reality from his point of view,” adding that there was much to explore in his street style photography. “Even a beauty shot had much more than beauty,” Lewin said. “He was truly a pioneer and a trailblazer inspiring many photographers.”

All in all, Klein once said that he had a clear idea of what he was after when taking a photograph. “You have your take on culture, politics or something. Then you see something that illustrates that, and you take a photograph. Fashion photography, depending on the period and the magazine, was selling the idea of how you should look, how you should hold yourself. Now a good part of fashion magazines are about how do you keep in shape, how to stay young, how to survive,” he said in 2013.

Even midway through his eighties, Klein saw through the facade of keeping up appearances. “I am always amazed to hear young models say, ‘I use this to take off my makeup. I use this before I go to sleep. I use this while I’m sleeping. I wash my hair with this.’ They know all these things but if they knew as much about politics or finance as they do about taking care of their bodies, that would be helpful to everybody. But I take off my hat to them because they have really got it down pat. They all have made a pact with the stuff that’s in the magazines and available to them. They made a choice and they have built a religion,” he said.

A black-and-white image of two models passing each other in a crowded crosswalk, titled, ”Nina and Simone, Piazza di Spagna, Rome, 1960,” is one example of Klein’s precision. En route to Rome, he stopped in Sweden to visit the camera manufacturer Hasselblad, which had just then released a latest-and-greatest telephoto lens. Discussing the ICP retrospective earlier this year, Campany explained how Klein was “a long, long way from those models. That was unusual for William. He usually liked to shoot with a wide-angle lens. On that crosswalk, you get these very compressed frames with the black and white of the crosswalk, and they’re wearing black and white dresses,” Campany says. “He was in radio contact with someone on the ground. He was talking to them. Everyone else in the frame doesn’t know what’s going on. It’s a fashion photograph meets an impromptu street photographer.”

His street photography captured far more than what was in the frame. It often encapsulated themes that were indistinguishable, but reflective of society. Referring to a photograph of a 1950s newsstand, Klein said, “The [New York] Daily News would have the headline, ‘Gun Man Caught in Love Nest’ or whatever. You would see ‘Gun,’ ‘Gun,’ ’Gun,’ one next to each other. On the top of the newsstand there would be a little plate where somebody could take a newspaper and put their four cents on the little plate. It was a traditional object that said a lot about life in New York at that period. The candy store owner trusted people to pay for the newspaper and, secondly, it worked.”

Interestingly, it was films, not fashion photography or any other art that Klein found most gratifying. Explaining his preference for films, Klein told WWD, “I find people don’t know how to read photographs. There isn’t this dialogue. Many people look at a photograph in an exhibition, they look at the title below and they snicker, ‘Ha,’ as if you caught somebody picking their nose, which is not my preoccupation. What you put in a photograph is not always perceived by the other people who look at them as what you wanted to say. There isn’t a culture of photography. You learn about music appreciation at schools or go to museums, but I found that generally people don’t study photography. There are a lot of things that can be said in photographs but people don’t relate to them.”

In keeping with that ideology, by his own assessment Klein considered the 1964 film he made of Muhammad Ali before he was a champion to be the work that he was particularly proud of. He also drew back the curtain on the absurdities of the fashion industry with the 1966 feature film “Who Are You, Polly Maggoo?” Other films were the Vietnam-era “Mr. Freedom” and a precursor to reality TV, “The Model Couple,” which documented a couple that were given everything they needed in an apartment, provided they were filmed 24 hours a day. (Needless to say both the couple and the film crew lost their cool over time.)

Orson Welles said of Klein’s debt 1958 film, “Broadway by Light,” that it was the first movie that really needed to be in color, according to Campany. And a decade later the equally boundary-breaking filmmaker Stanley Kubrick told Klein upon meeting him, “William, you’re probably too far ahead.”

Klein once explained why he was so fond of the Ali film. Although Ali was at one time “somebody that everybody thought was a clown,” he went on to become the greatest sports hero of the 20th century. “For many people, he’s also the most important American, because he’s a man who believed in his own convictions and sacrificed his title, money and the product that he could have acquired, when he was exiled from boxing. There are very few Americans who refuse something on the basis of their convictions and I find that this is something very extraordinary,” Klein said in 2013.

Quick with a one-liner and a ultra-keen observer, Klein needed no special training in dealing with strangers. Recalling the early days of street photography, Klein said, “People weren’t used to having somebody walking around with a camera taking their photograph. There wasn’t much reaction. Most people thought, ‘If this guy with a camera is taking my picture, well, he has a right to.’ Also, people like to be convinced they are worth photographing. There used to be a TV program called ‘Queen for a Day,’ and being photographed was something flattering. If someone would ask me a question, I would bulls–t them. I’m a New Yorker. I would say, ‘I’m working for the [Daily] News as that Inquiring Photographer.’ People would ask, ‘When is it coming out?’ And I would tell them, ‘Tomorrow. We work fast.'”

Switching tracks to photography enabled Klein to capture images that were as frenetic as his mind and work habits. “I had this feeling if I photograph this group of people moving this way and that way, with the combination of the architecture and the typography and everything, then all my ideas about New York would come into place. And within two-hundredths of a second, I would get this image,” he told WWD in 2013. “To me, it was kind of like hunting. Before that, I was doing paintings that were very thought-out and geometrical. Photography was a kind of liberation. It was all about talking about things that I couldn’t put in the abstract geometrical paintings, and I welcomed that.”

Prior to winding back his workload in recent years to focus on exhibitions and select projects, Klein was adept at progressing from one endeavor to the next and routinely finessed multiple ones at once. Asked what he would like people to think of, when they see his world, Klein told WWD in 2013, “I would like people to think this man is worth a couple of million dollars more for what he has contributed and [for them] to give that to me [laughter]. You do things for yourself and you do things for other people and you hope that these things coincide.”

Best of WWD