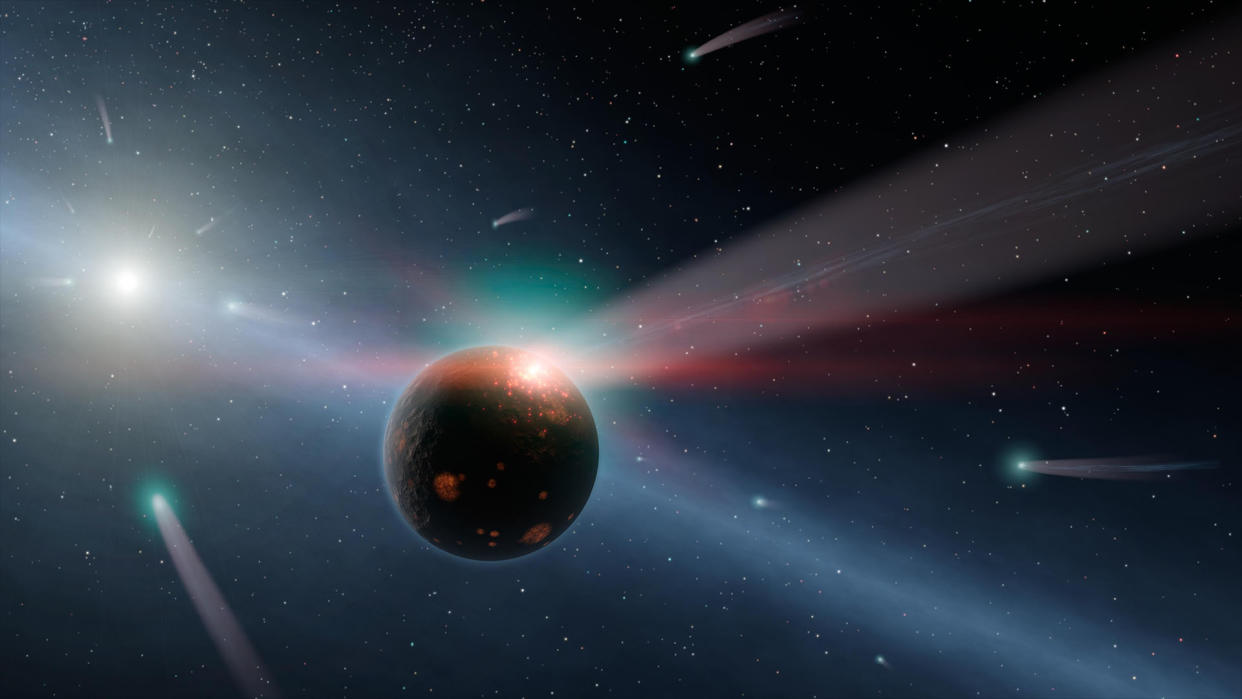

'Bouncing' comets may be delivering the seeds of life to alien planets, new study finds

The origin of life is one of the greatest scientific mysteries in the universe. Currently, there are two prevailing theories as to how it happened on Earth: The ingredients for life emerged from a primordial soup on our planet, or the molecules necessary for life were "seeded" here from elsewhere in the cosmos. With the latter theory in mind, a team of scientists has come up with a model for how this delivery could have occurred — and how it might happen on planets beyond our solar system.

In a paper published Nov. 14 in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society A, the authors describe how "bouncing" comets could have distributed the raw ingredients for life — called prebiotic molecules — throughout star systems similar to our own. The team focused on simulating rocky exoplanets orbiting sun-size stars.

"It's possible that the molecules that led to life on Earth came from comets," Richard Anslow, an astronomer at the Cambridge Institute of Astronomy, said in a statement. "So the same could be true for planets elsewhere in the galaxy."

In recent decades, astronomers have proved that some comets and asteroids contain prebiotic molecules, including amino acids, hydrogen cyanide and vitamins, such as vitamin B3. While none of these organic compounds constitutes life in its own right, they are all necessary for life as we know it.

The researchers found that comets could, indeed, deliver intact prebiotic molecules directly to planets — but only under certain circumstances. First, the comet has to be traveling relatively slowly — at or below 9 miles per second (15 kilometers per second). Otherwise, the heat it would encounter while entering a planet's atmosphere would burn up the delicate organic molecules instantly. (For comparison, NASA estimates that Halley's Comet was moving at roughly 34 miles per second, or 55 km per second, during its last close approach to the sun, in 1986.)

The team calculated that the best place for comets to hit the cosmic brakes would be in "peas in a pod" systems, where a cluster of planets orbit in close proximity. This would cause an incoming comet to bounce from one planet's orbit to the next like a pinball. As it traveled, it would decelerate, until it eventually entered one planet's atmosphere slowly enough to deposit its prebiotic cargo. Crucially, the team also found that planets orbiting smaller stars or planets in less densely packed systems would be less likely to receive successful comet deliveries.

RELATED STORIES

—City-size comet racing toward Earth regrows 'horns' after massive volcanic eruption

—Volcanic 'devil comet' racing toward Earth resprouts its horns after erupting again

While this might not be the only avenue for life to arise in the galaxy, the researchers say their simulations could help give scientists a better idea of where to look for extraterrestrial life. And with more than 5,000 exoplanets discovered so far, narrowing down this search will become increasingly important.

"It's exciting that we can start identifying the type of systems we can use to test different origin scenarios," Anslow said. "It's an exciting time, being able to combine advances in astronomy and chemistry to study some of the most fundamental questions of all."