The Boston Athenaeum Turns the Page

It’s said to be as Bostonian as the Common. Ralph Waldo Emerson’s father was among the original trustees who launched the place in 1807. It’s where Nathaniel Hawthorne blew off editing work at the American Magazine of Useful and Entertaining Knowledge so he could discover the books, paintings, and sculptures that stoked his writerly imagination. The 19th-century intellect Margaret Fuller spent untold hours there with the goal of alleviating her “poverty of knowledge” and succeeded wildly. Robert Gould Shaw, who commanded the all-Black 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry in the Civil War, was a shareholder. After achieving celebrity status with Little Women, Louisa May Alcott borrowed piles of books that fed her subsequent novels. When you visit today you can look over Alcott’s “charging records” and then ask a librarian to point you to the actual volumes that Alcott savored. They remain on the shelves, part of a collection of more than 600,000 books and objects at the venerable, beloved, and utterly indispensable Boston Athenaeum.

“Alcott was very into trashy novels,” Leah Rosovsky noted at the Athenaeum (which is generally pronounced Ath-a-NEE-um), on a recent sunny morning. Since May 2020 she has been the Stanford Calderwood Director of this neo-Palladian jewel of a private library near the apex of Beacon Hill at 10½ Beacon Street, a half block from the gold-domed Massachusetts State House. The two institutions make a natural pairing, the one being the seat of Massachusetts politics since 1798 and the other being a kind of greenhouse where New England’s cultural life sprouted more than 200 years ago.

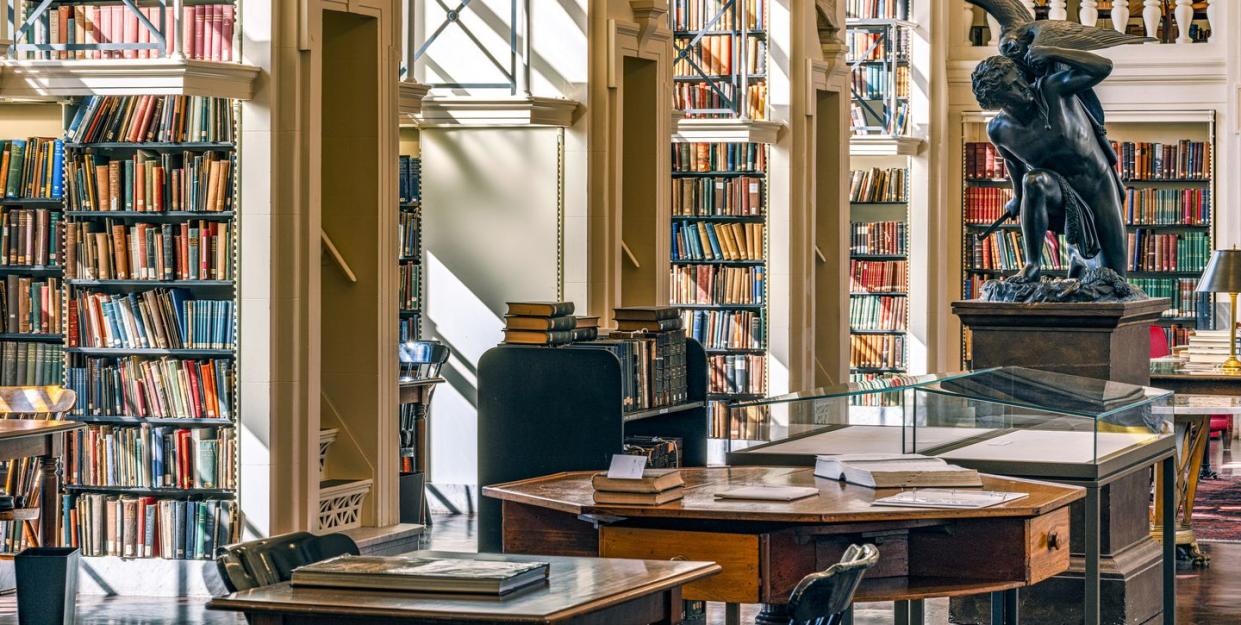

The Athenaeum’s five floors of reading rooms are lined with busts of such luminaries as George Washington and the Marquis de Lafayette (a piece that Thomas Jefferson once owned). There are paintings by the likes of John Singer Sargent and Gilbert Stuart, whose famous unfinished Washington portrait hung here until the National Portrait Gallery and Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts jointly bought it in 1980. The largest extant portion of Washington’s personal library resides here, as does the King’s Chapel Library, a set of 221 ecclesiastical books sent over from London in 1698 for Boston’s first Anglican church. Enormous windows look out behind the Athenaeum onto the old Granary Burying Ground, the permanent home of Paul Revere, Crispus Attucks, John Hancock, and other heroes of America’s founding era. Hawks love to perch on the Athenaeum’s terraces and bask in the sun. That morning Rosovsky pointed to one circling above the cemetery while school groups stood around staring at the old slate headstones.

It’s not your standard issue urban tableau, and it’s not any old library. Ducking into the Athenaeum from the clamor of inner Boston is to enter an oasis, a secret hive that has drawn writers, artists, academics, politicians, historians, scientists, and armchair seekers of knowledge and literate companionship for more than two centuries. “The history of this place is all about curiosity,” said Rosovsky, who came to the Athenaeum from Harvard Business School, where she served as the dean’s administrative fellow.

It’s a history that continues to evolve and refresh itself. Since August of last year, the Athenaeum has been undergoing a $17 million renovation, adding new spaces—including a revamped children’s library, members “living rooms,” and an adjoining café at 14 Beacon Street—and sprucing up old ones. It comes 20 years after the last overhaul, which brought much-needed modernization to the Athenaeum but covered the lobby’s gorgeous arched windows. The new plan will open them back up. This fall, when you step into the building, you’ll once again find yourself in an airy, light-filled, soaring space, thanks to a sensitive reworking by the Boston architect Ann Beha. The revised lobby is a handy metaphor for the new era of the Boston Athenaeum that is starting this year. “Yes, it’s about strong traditions,” Rosovsky said of the institution. “But the Athenaeum has always been changing, becoming more open, more welcoming.”

The Boston Athenaeum is an independent membership library, the largest in the United States. Other notable membership libraries include the New York Society Library and the Athenaeum of Philadelphia; these date from the days before public library systems were established. Sixteen of them still exist.

Its roots are deeply Brahmin, but anybody can join. In 1839 an annual membership went for $10. An individual membership now runs $460 a year, which is a steal considering that you get access to the Athenaeum’s robust collection—vast digital offerings, teeming stacks, invaluable rare books, and a constant flow of new acquisitions—and nonpareil public events such as book launches, lectures, and recitals. (The Athenaeum also offers family and youth memberships, as well as day passes.) Rosovsky describes the membership roster, which currently numbers about 3,000, as “Boston writ large.” Even so, some members live as far away as Los Angeles, and virtual events have opened the Athenaeum to a global audience.

When I asked the presidential historian and former Bill Clinton speechwriter Ted Widmer about the Boston Athenaeum, he was rhapsodic. “It’s a great and venerable institution,” he said of a place he’s been visiting since he was a boy. (It also became an escape hatch during his undergrad days as an editor at the Harvard Lampoon.) “But it’s not the Brahmin institution it once was. It’s about people who are interested in literature and science and politics and new ideas.” Widmer is an Athenaeum proprietor, meaning that he is one of the library’s 941 shareholders. Shares can be inherited; often a family will hand off its equity to a bookish member of the next generation, as happened in Widmer’s case. Up until 1970 the shares were traded on the Boston Stock Exchange. Today they are available for purchase at $5,000 each. “It’s a donation, really,” Rosovsky said.

You don’t need to be a trustee to go deep into the treasure box of the collection. “In the realm of favorite things at the Athenaeum, it’s hard to limit yourself,” Cullen Murphy told me. Murphy is a longtime editor at the Atlantic and an Athenaeum member going back 35 years. He mentioned Chester Harding’s oil portrait of historian and author Hannah Adams (who in 1829 became the first woman to gain membership) and a rare early copy of Nathaniel King’s famous map of the Lewis and Clark expedition, which King created based on cartographic information the explorers sent east via courier. “It’s the most amazing thing,” Murphy said.

You can pore over original Cartier drawings from the 1920s illustrating designs for gold lipstick holders, cigarette cases, and powder boxes. You can leaf through a collection of books published in Native American languages, such as a “Cheap and Concise” Ojibwa dictionary. You can peruse a database of the free Black citizens of Boston covering the years 1820 to 1863. You can sift through the eerily depopulated photographs that Berenice Abbott took of Boston’s streets in 1934. (If you’re looking for the latest issue of this magazine, Town & Country is kept in the Newspaper Reading Room next to the Times Literary Supplement.) Rosovsky pointed out that the hands-on experiences you can have with the King map and other treasures is what sets the Boston Athenaeum apart from the best museums, where the rule is Do Not Touch. “You can have a real experience with the material here,” she said.

After the 1807 founding, the Athenaeum bounced around from location to location until a competition was held in 1846 to determine who would design a new building. The winner was Edward Clarke Cabot, whose résumé included a stint as a sheep farmer but no formal architectural training. It was Cabot’s first commission. The design he came up with for the Athenaeum’s new home featured a striking neo-Palladian façade clad in ruddy sandstone; it stuck out like a sore thumb amid Beacon Hill’s staid townhouses. Some locals were less than pleased when it opened, in 1849. “This building was considered avant-garde,” Rosovsky said. Aside from the outer shell, the structure today isn’t quite the one Cabot conceived. It was gutted in 1913, with the interiors remade and two floors added, including a fifth-floor reading room that remains one of the building’s best-loved spaces. Change has always been part of the recipe.

Yet there’s no doubt that part of the appeal for longtime members and newcomers alike is that the Athenaeum feels gloriously anachronistic. “I think their strength is actually how old-fashioned they are,” Widmer told me. “I remember seeing E.O. Wilson give a talk. It was magical. That’s what I want: the world’s top expert on insects talking in a room with all these classical statues standing around. That kind of thing still has a lot of power in a world that’s given to media gratification, in which we have these experiences on our cell phones and then it’s hard to remember what they were 20 minutes later.” Members and the general public find camaraderie in these gatherings, at which brie is nibbled, chardonnay is sipped, brains are picked, and new ideas are born. Does that translate as old-fashioned? For a lot of people it’s the best way to be fully engaged in the present.

The Athenaeum, Widmer said, represents a uniquely Bostonian brand of community awareness and cultural engagement, that old New England ideal that coursed through our national life and helped form the attitude Americans have about themselves: We are a good people. “Even though Boston may at times have an inflated sense of its relevance to the rest of the United States,” he said, “we do all of us gain from the continuity of its institutions and traditions.” Murphy, who wrote two books at the Athenaeum, put it another way: “If you look at it over time, you see intellectual and social currents that influenced the entire nation intersecting within the walls of the Athenaeum. The fact that Robert Gould Shaw had a share tells you something. It’s not just people who have their noses in books. It’s people who are out in the world.”

“I feel so lucky to be a steward of this kind of institution,” Rosovsky said, as light streamed through her office window, another group of schoolkids milled around the Granary Burying Ground, and the faint sounds of renovation played in the background. Coming to an American landmark every weekday—it’s dream job stuff. And then there’s the fact that this 215-year-old institution continues to be a positive force in the 21st century. “When I think about what we need, as Boston and as a society, I think about more opportunities to talk about ideas, even difficult ideas, in a way that is accepting and supportive of exploration,” Rosovsky said. “That’s a function the Boston Athenaeum has always performed, can still perform, and will continue to perform.”

This story appears in the Summer 2022 issue of Town & Country. SUBSCRIBE NOW

You Might Also Like