Books by Sarah Ghazal Ali, Carolyn Hembree and Michael Ondaatje for National Poetry Month

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

National Poetry Month, observed each April since 1996, mirrors the labors of poets themselves.

Poets bend close to the earth, and to its people, noticing the hurts and homemade medicines, beautiful sentiments and tragic story suffusing our lives. These elements perpetually exist, but poems call them out into a greater clearing.

Similarly, poetry is always here for us, among the ever-present glories of being alive. But the April observance calls us to a special, more sacred attention. Here are brief glances at three 2024 poetry titles worth such reverent and delighted noticing.

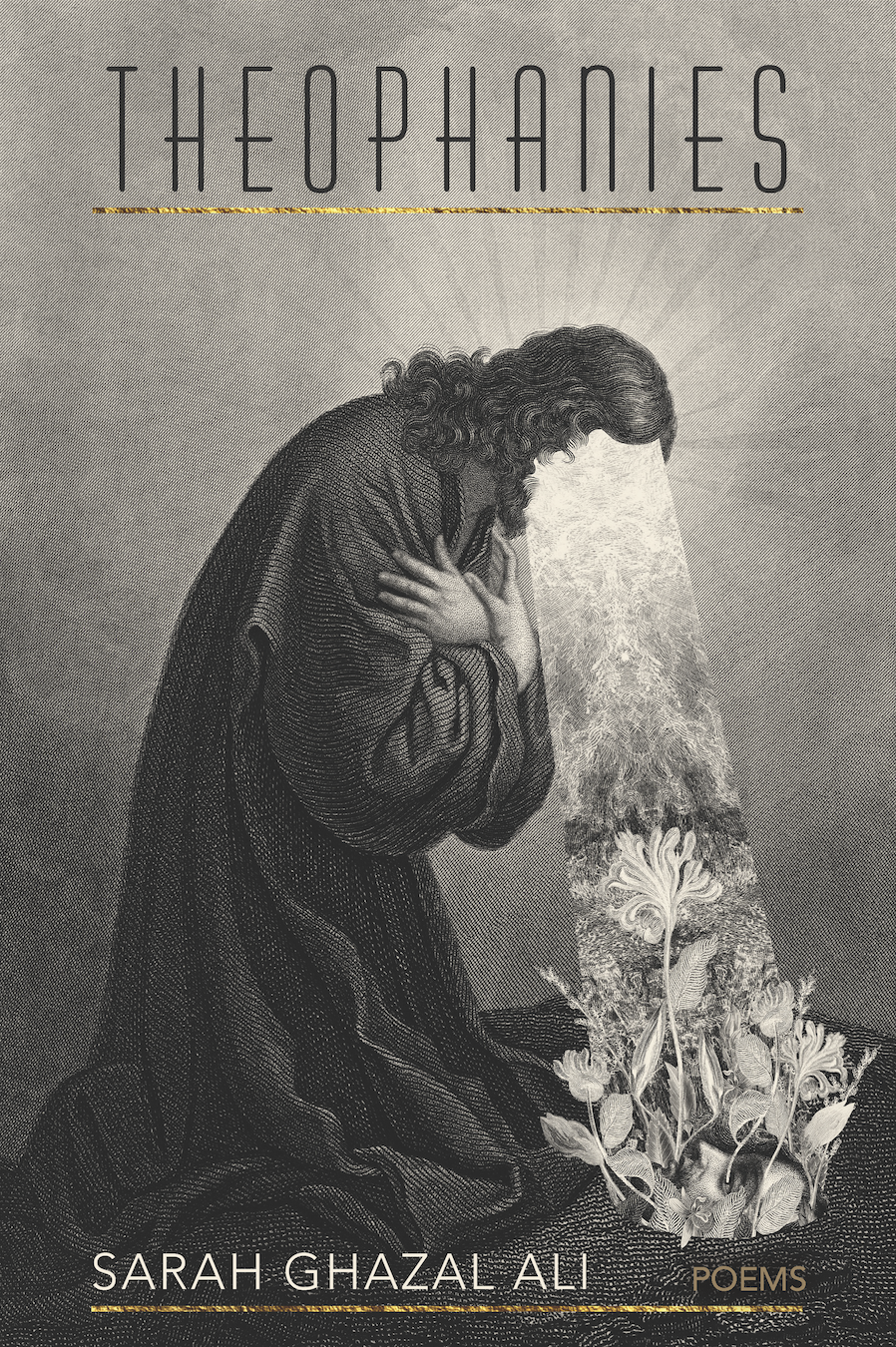

Sarah Ghazal Ali, "Theophanies"

Sarah Ghazal Ali’s debut represents an early fulfillment. From surface to substance, the poems within resemble one of the great book covers in recent memory: wild, ecstatic, very nearly miraculous.

And if poems are like prayers and vice versa, Ali fulfills that connection on the opening page, writing “The places I’ve prayed—elevators, Victoria’s Secret / fitting room, the muck-slick meadow after rain—will testify for or against me, / spilling through my Book of Deeds / in ink of blood or honeyed milk.”

In the most intimate layer, the most secret place, Ali’s exquisitely searing debut fulfills her own name which surrounds ghazal, an ancient Arabic poetic form. These pages form a portrait of an artist for whom poetry is the center, the reason to live.

Throughout, Ali mingles references to Biblical and Quranic texts with her experience of womanhood, revealing their conversation in verse, displaying how the sacred inhabits bodies and bodies add their own punctuation —question marks, exclamation points, ellipses — to holy scriptures.

Ali writes in parables and vivid observations (“A pair of apples blistering under the sun— / my eyes have been so saturated”); details her god’s creative process, fashioning the people she loves in and apart from language; muses over what it means to be a woman within a faith, within a world, always voicing its expectations of women.

“I submitted once, faithfully, and it was years / before I bloated with shame,” she writes in “Magdalene,” before considering the common roots of terms like submission and Islam.

Ali writes her own body in parallel to Scriptural stories (“Self-Portrait as Epiphany” ranks high among the many highlights here) and crafts a personal set of proverbs (“In good towns, good houses mourn what dies / outside by closing windows,” she writes in “Roadkill Elegy”).

And theologians of all faiths should teach Ali’s descriptions of the angel Gabriel (“O ungendered & sex- / less courier / O jagged nail / fattening on His finger”) and faith itself (“Never heavy, and whole / with or without me”) — not as the sum of these concepts, but some of their many moving parts.

Conviction spurs the poet to create, sometimes as a counter to their god’s work, sometimes as a collaborator and sometimes in some blurred space between the two (“Like God, I’ll create in my image,” Ali writes in one poem). Whatever Ali is working out, from the inside out, these poems represent art indivisible from faith and looping all the way around.

Carolyn Hembree, "For Today"

Artists across disciplines offer distinct readings of what the dash means — the dash chiseled between birth and death years across the headstones we eventually sleep beneath. In her latest collection, New Orleans-based poet Carolyn Hembree doesn't so much define the great, untold middle of our life cycles as describe them: in weather patterns, as an atmosphere shaping and revealing our desires, our bonds, our quiet fates.

In the opener "Some Measures," Hembree reveals how the birth and death of beloved others can't help but frame her worldly feeling: "What’s taken, / what’s taken in—not my milk (she fasts), but a dirge / she heard through coral walls. At your noon funeral, / my pregnant shadow pooled under me. Amen."

Life proceeds as it must, unspooling into the music of Captain Beefheart and Violent Femmes, the language of "Rilke, / gospels, one-liners, a gun poem composed decades / before to keep from offing yourself—now gone / or going."

Hembree moves, grieving and preparing to be grieved, through humid particles of her child talking, past a "smashing, muddy river," between "scrolled symptoms and elevators." Clouds "about to rain" and softening mornings move her, as do her neighbors domestic and wild.

Hurricanes and other plagues strike, with their attendant boil orders and makeshift homeschools. Frogs hum in "crescendo and decrescendo," and fig trees simply "exist." The dash stretches still. The nearness of grief abides as the poet moves through the world "like moss" — always craving moisture — and observes the bending of our bodies.

"A friend told me grieving too long is selfish, warps the griever the way rainy seasons warp old wood / Maybe I want to be warped," Hembree writes at one point.

The dash responds to the date to its right, but that isn't all the dash — or the poet — does. Hembree lets moisture soak her skin and patches a property's leaks; celebrates all that remains while tracing shapes around memories; meanders, flowing to and from springs, and writes in rocksteady rhythm.

These contradictions, beautiful and strange, comprise the dash as much as anything; Hembree knows this full well. "For Today" is a series of dampened moments readers will long to absorb alongside the poet.

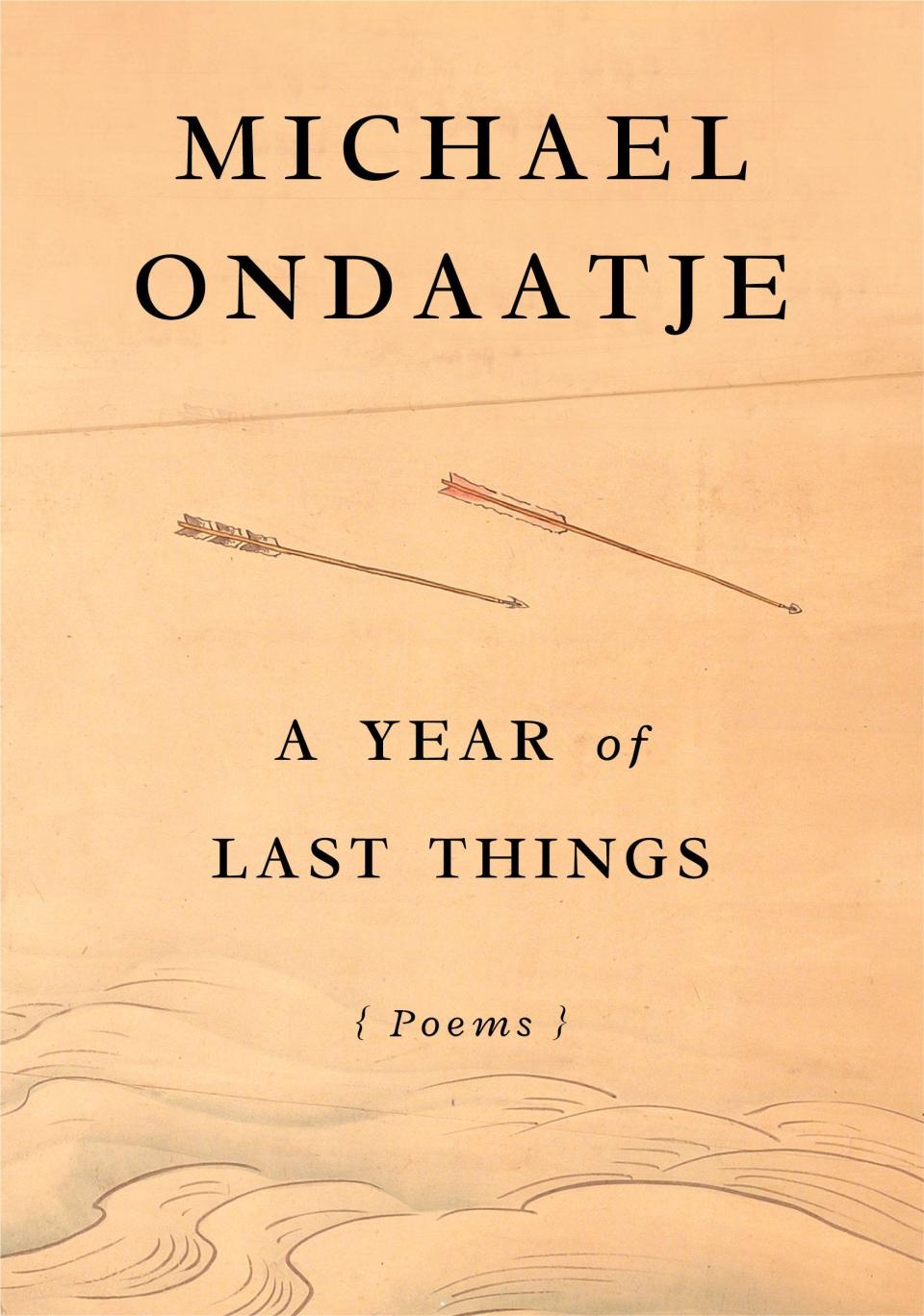

Michael Ondaatje, "A Year of Last Things"

Michael Ondaatje — a former Unbound Book Festival keynote speaker — returns once again to his first love, poetry. Although a companion across the decades, the form is less attached to his name and reputation than renowned novels such as "The English Patient."

A reflexive style and masterful touches define these poems as Ondaatje writes of 3 a.m. memories, 7 a.m.'s "strange awakening thought," the burden slipping and easing from the back of all his years, and the quietly persistent presence of what has and could have been.

Ondaatje is self-referential, never self-indulgent, in his honorific treatment of words themselves. He opens the poem "Lock" — and the collection — with this all-time verse:

Reading the lines he loves / he slips them into a pocket, / wishes to die with his clothes / full of torn-free stanzas / and the telephone numbers / of his children in far cities

Within "Definition," he studies "the plotless thirteen hundred / pages of a Sanskrit dictionary / with its verbs for holy obsessions." With just four lines, he evokes a writer's whole world in "The Cabbagetown Pet Clinic," describing the creative labor undertaken over a vet's office, hovering among "The howls, the heavy breathing, the sighs / from that faraway untranslated world."

And "A Night Radio Station in Koprivshtitsa" delivers lyrical descriptions worth of Ondaatje's canonical novels, writing of "some museum of the night," creating the weather beneath a "medieval firmament of bruised clouds, thunder, old chaos."

"A Year of Last Things" is technically brilliant and endlessly soulful, a hymn to the language Ondaatje loves, neither side of that equation ever losing to the other.

Aarik Danielsen is the features and culture editor for the Tribune. Contact him at adanielsen@columbiatribune.com or by calling 573-815-1731. He's on Twitter/X @aarikdanielsen.

This article originally appeared on Columbia Daily Tribune: This National Poetry Month, spend time with these 3 rich reads