Bonefishing Off Bimini With Bobby Knight

Billy Black

On Halloween, a friend of mine asked me to share the most unexpected number in my phone. Over 15 years covering the yachting industry, I’ve collected quite a menagerie of characters in my contacts list. But the answer was pretty simple: longtime Indiana Hoosiers coach Bob Knight. What made the conversation particularly surreal was checking the news the following day, and finding out that Knight had passed away at the age of 83.

I spent one of the most memorable weeks of my entire life with Knight in 2015, bonefishing off the tiny island of Bimini in the Bahamas for a profile in Anglers Journal magazine entitled “Here Be Dragons.” I was young and hungry and desperate to elevate beyond writing for trade magazines, and Knight was my big chance—the most high-profile person I had come into contact with professionally at that point. I was determined to write the best article of my career.

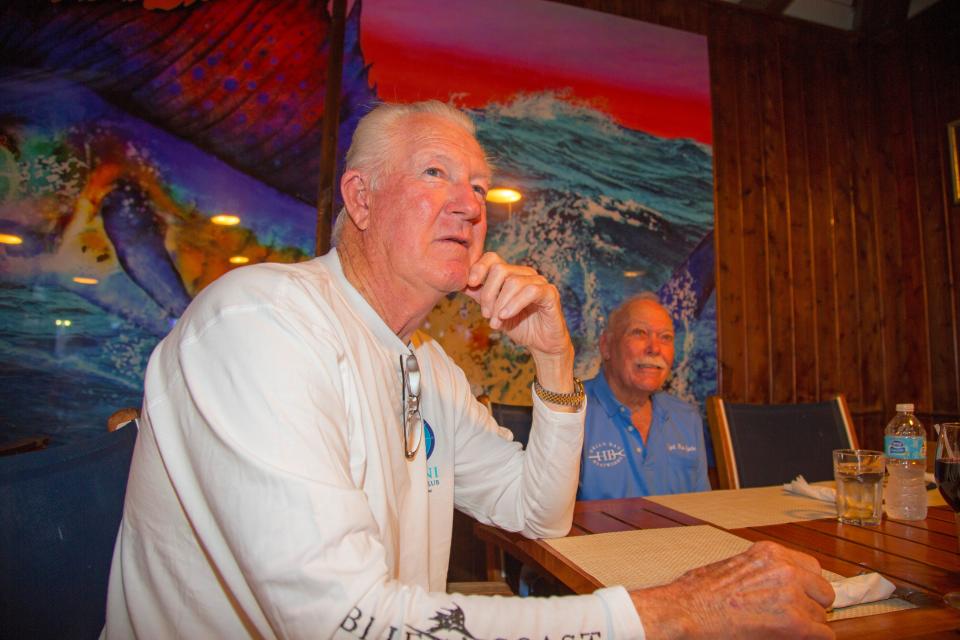

Knight made it easy. The legendary coach had perhaps an even more legendary temper, and he lived up to his rep. He remains the most larger than life person I’ve ever met, and probably ever will. He was equal turns worldly and gentlemanly, crass and terrifying. Above all, he was hilarious, armed with coarse coach humor characterized by bullying one-liners. At dinner one night at the Bimini Big Game Club, he described a former Indiana booster as so unathletic that “he probably couldn’t dribble a basketball twice without bouncing it off his dick.” I laughed so hard I choked on a conch fritter.

By the time I got home, my notes were brimming with anecdotes and observations. I felt good about the piece I wrote, and so did my peers—it won the 2015 award for profile writing from Boating Writers International.

Knight and his people didn’t feel the same. Shortly after the article came out, I was sitting at a bar in the Nashville airport at 8 a.m. on a Sunday morning when my phone rang. It was Knight’s PR rep, who informed me that he and Knight hated the article, that I didn’t know what I was doing as a journalist, and that I owed them both an apology. I told him I would call Bob and try to smooth things over. “But you,” I said, “you can go fuck yourself.”

Two days later I called Knight, knowing I was in for a doozy. The instant Bob picked up he laid into me. “I knew you were a cocksucker from the moment I laid eyes on you,” he fumed. He also told me the article was “the biggest piece of shit he’d ever read.” I suggested he work on his reading comprehension skills. The conversation deteriorated from there until we both slammed down our phones. “Don’t ever contact me again,” he said. I replied: “I don’t think that’ll be a problem, Bob.” It was to be our final exchange.

Whenever I tell people about this story, they usually expect me to hate Bob Knight. But the truth is, I never hated him. If you study your Knight history, you know that, for all his faults, he did both good and great things in his life and career. I believe the most telling of all his accolades, the three national championships and the Olympic gold included, is that his teams had an 80-percent graduation rate, double that of the national D1 average. When I think of Knight, I recall the line from Moby Dick that compares Captain Ahab to a mountain eagle, who even when swooping down into the blackest gorges flies higher than the birds on the plain. Knight was famous for being difficult, and in doing so, getting the best out of his players. He did the same for me. —Kevin Koenig

Bob Knight is being too direct. The legendary basketball coach is throwing flies at bonefish on the morning of the first day of a three-day fishing trip to Bimini, and he is casting too fast, too hard. The proverbially skittish bonefish—the favorite meal of every toothy, scary thing that lurks beneath these paradisal waters—hunker together in small groups in the gin-clear flats, maddeningly close to the boat. But each time Knight casts, his line slaps the water, and his fly lands with too big a splash.

Knight’s nickname in college was Dragon, and right now, standing tall on the bow of the boat in the bright, hot sun, his leader licking fiercely at the water’s surface like a flame, he looks the part. And the fish are running scared. They skitter in every direction, fast as can be, earning them their moniker: the gray ghost. Their mortal fear is palpable. I wouldn’t wish being a bonefish on my worst enemy.

Our guide, Bonefish Tommy, preaches to Knight from high up on the pulpit of his skiff, his voice thick with consternation and the musical lilt of the islands. “You’ve got to come in more gentle, Baw-bee. Lay it up over the top and drop it down nice and soft, like a … like a parachute!” He pleads. “You don’t want to scare the fish. They scare real easy, Baw-bee.” Knight may or may not hear him. But he definitely isn’t listening. (That will become a running theme of my time with Knight, trying to guess if the 74-year-old hasn’t heard me or is simply ignoring what I said.)

Later, Knight—a seasoned fly fisherman with more than five decades of experience — will say that the reason his trajectory was too flat is because he is used to wading into the water instead of casting from a boat. He’s waded for bonefish in the Turks and Caicos five or six times, he reminds our group on multiple occasions, and each time he caught more fish than he knew what to do with. But today Knight is getting skunked. And the great man is not happy.

Buttons

Bob Knight is nothing short of a tour de force. Think of the strongest, most charismatic personality you’ve ever met. Now multiply it by 10. That’s Bob Knight. He is constantly testing people. Bullying, cajoling, charming, asking pointed questions out loud so everyone can hear. One minute he will lean over conspiratorially and whisper a joke in your ear. You will laugh, because Knight really is a funny bastard. You will think, This man really likes me. Then you will ask him a question he doesn’t quite like the bend of. And he will look you square in the eye with nothing short of malice and go stone silent. You will think, Wow, this guy actually hates me. Truth be told, in my five days with Knight I was never quite sure where I stood with him, which is ironic, since Knight is famous for not mincing words. His naked contempt for the media is no secret. He calls us “the press,” and spits it out like it’s an epithet.

He has his reasons. Knight has been a public figure since 1965, when he accepted the head-coaching job at West Point at the ripe old age of 25. And ever since then The General (another nickname, though he was actually a private first class) has been waging war against those who would purport to tell the world about him. Because despite the best efforts of journalism professors and well-meaning editors, newsrooms are far too often brutal places for those who refuse to sugarcoat hard truths. If it bleeds, it leads, and Knight’s words can cut to the bone.

His temper is legendary, and part and parcel of who he is. He understands this and wields his fury like a man who brought a baseball bat to a fistfight. Even at his age, when Knight unleashes he can be terrifying. Not that he seems to do it very often these days. “I don’t really get mad at people much anymore,” he says to me in an early moment of reflection on the skiff. “But I still get mad at things. If I brought the wrong fly out here, or packed the wrong box for this trip, I’d get madder than hell. But by now I know who the people are who make me angry, and I just stay away from them.”

This is major progress.

You know about the chair. Everybody knows about the chair. The one he flung onto the court in a fit of rage during a game in 1985 to protest a call. In a career full of incredibly high highs, that low low became his signature moment. I suggest you not ask him about it if you see him on the street.

His temper, of course, has gotten him in trouble too many times to count. There was the time he was arrested in Puerto Rico during the Pan-Am Games in 1979, while serving as head coach of the U.S. national team, for allegedly striking a cop (more on that later). The press had a field day with that one. Truckloads of sanctimonious columnists spilled ink calling for his head, saying he had no place representing America in international competition. Indeed it would take the unmitigated support of legendary U.S. congressman Tip O’Neill to get Knight instated as the U.S. Olympic coach in 1984. Knight led the U.S. team to gold, but not before sending Charles Barkley packing for being too fat. “He came in at 283,” Knight says of the Round Mound of Rebound. “And he lost 9 pounds in the first week, and then we had a week off. I knew he was going home, and I told him he had to lose 9 more pounds during that week. But when he came back to practice, he had actually gained weight. I told him ‘Charles, you’re gone.’”

You may also have seen the grainy YouTube footage of what looks like Knight grabbing one of his own players by the throat during practice in 1997. That incident got him put on a “zero tolerance” policy at Indiana. Three years later he was alleged to have grabbed Indiana freshman Kent Harvey by the arm, delivering a somewhat spirited lecture to him on civility and respect for his elders. Harvey complained to the school. And that was the end of Knight’s time in Bloomington. Harvey’s stepfather, it turned out, was Mark Shaw, a former Bloomington-area radio host and an outspoken critic of Knight. Many smelled a conspiracy. During his farewell speech, Knight asked 6,000 adoring, enraged supporters not to hold Harvey responsible for his firing. He may very well have prevented a lynching.

Knight’s good friend, former college roommate and all-time NBA great John Havlicek was also along on this fishing trip. He says of Knight, “He’s always been like that. Since he was 17. Everybody’s got buttons. Robert’s just got a lot of them. And they’re big.”

But with all the backstory on what a tyrant Knight is, the surprising thing is how charming he actually can be. There’s a twinkle in his eye. He smirks a lot, though rarely smiles. He is constantly joking and taking the piss out of people. That nickname Dragon? He got it after he showed up freshman year at Ohio State and told everyone he was in a gang of car thieves back home called The Dragons. Everyone believed him. But as it turned out, The Dragons were a total figment of his imagination. “I just make up these stories to amuse myself sometimes, to see how gullible people are. Life can get pretty boring otherwise,” says Knight.

Another thing about Knight that you might not expect is that he is surprisingly good-looking. He looks like an aging movie star who was cast to play Bob Knight in a biopic. A shock of stubborn white hair that he cuts himself (you can tell), fiery blue eyes, tall—mix that with the mantle of his celebrity and it’s a killer combination. He’s 74 and women still respond to him. A few of the native Bahamian girls, workers at the hotel and plump in the island way, literally clung to his side whenever they saw him. Shy, middle-aged housewives approached him nearly every time we ate in the restaurant at the Bimini Big Game Club, where we were staying. They stand meekly off to the side, waiting to introduce themselves, their sons, their husbands. And Knight eventually notices them and says something disarmingly funny, and you can see it, the women actually melt. Right there in front of their husbands.

As we posed for a photo in front of the Big Game Club’s front sign, a passing tourist, in her mid-30s with an infant in her arms, stopped and stood off to the side so as not to interrupt the shot. Knight saw this, and half jogged out from the back of the photo to grab her lightly by the shoulders. “Miss, you need to get in here with that baby to brighten this shot up. Come on now, stand right here … of course I’m sure.” She did as she was told, wide-eyed. After the picture she came up to me and asked, “Who was that guy?” As if Superman had just swooped down from the sky.

I said, “That’s Bob Knight.”

“Who’s he?” she responded.

“Go tell your husband you just met Bob Knight,” I said. “He’s a basketball coach.” And she hurried off.

Keeping Score

From Knight’s mouth flows a constant stream of stories. Some entertaining. Some insightful. Many both. He is able to plumb a seemingly fathomless trove of life experiences to make his point, or just to make people laugh. Who else can say that they got over on Michael Jordan, busting his chops in an Olympic locker room? Or went golfing with President Gerald Ford? “We’re a good pair,” Ford told him, “everyone’s afraid of you, and no one will say no to me!” Or singing the “Marine’s Hymn” to Ted Williams as they fished a stream together, and cracking up as Williams, the Marine fighter pilot, would snap to attention and salute. Ted Williams by the way, that guy—if Bob Knight is one of the most charismatic people I’ve ever met, Ted Williams must have been concocted in a lab somewhere using the DNA of Cary Grant and Zeus himself. At one point in the beginning of our trip, Knight and legendary angler Stu Apte (who was also along for the ride) traded stories about Williams for what seemed like hours. That was all they wanted to talk about. And I started to wonder who exactly I was there to write about.

But for all the triumphant stories Knight has to tell, the Olympic victory, the three national championships at Indiana, and the one as a player he won at Ohio State, it’s the losses that stick with him the most. In the beginning of the trip, as we pulled into the Bimini customs dock in our Tropic Ocean Airways seaplane, the thunderous engines died down to a quiet whir, and all I could hear was Knight in the back of the plane telling a story. “I can still see it just clear as day,” he said, “the kid was off in the wing, and he shot the ball as time ran out, and it glanced, I mean just touched, off the backboard, and went in. And we lost. Yep. 23-22.” The score jarred me to attention. I found out later he was talking about a game that happened in 1962, when he was the assistant coach at Cuyahoga Falls High School in Ohio.

Later on I’d ask him how many Final Fours he took his Indiana team to. “Four or five,” he grumbled, “or whatever it was.” (It was five.)

By the middle of our second day in Bimini, bonefishing was a losing proposition for Knight. We had switched guides from the first day, from Bonefish Tommy to Eagle Eye Fred, but no one was spotting many fish. And when we did see the bones, they were mostly in the shallows, in maybe a foot or so of water, which made them even more wary of Knight’s line whipping at the water. He never did quite get the cast down, I don’t think. He was a little out of practice, he admitted. He had worked on tying knots for hours the night before the trip. The ins and outs, the slips and ties, all beginning to fade from memory. “You forget stuff when you get older, boy,” he said to me as he labored in the bow of the boat, hunched over one of his knots. “That’s what you get to look forward to.”

A Chickenshit Scenario

The fact that the fish were scarce was actually a blessing for me. Knight and I really got to talk. I noticed the night before at dinner that he drank sweet iced tea throughout. Not exactly the norm in the barroom at the Big Game Club. I asked him if he drank alcohol. “Not really,” he said. “No real reason for it, I just never found anything I liked the taste of.”

Then he revisited one of the first questions I had asked him when we got to the island. The great barroom debate: “Who is your all-time NBA starting lineup?” He originally said Oscar Robertson, Bill Russell, Jerry West and Michael Jordan, and left the fifth spot open. But with some time to ruminate on the query, now he had this to say: “You know, I’ve been thinking about this chickenshit scenario you’ve asked of me.”

I wracked my brain trying to think of which chickenshit scenario that might be.

Then he went on. “You can’t do an all-time starting five. Because you need Jordan, Bird and Magic. But you also need Oscar, West and Bill Russell.”

“So you’re saying you want a sixth man? OK.”

“No! I don’t want six, I want eight!”

We also talked about Mike Krzyzewski, his former protégé when he coached at West Point. Coach K would go on to break Knight’s all-time wins record in NCAA Division I basketball at Duke. Krzyzewski had been a player at West Point before becoming an assistant coach there, and Knight mentioned that after he graduated he went to Korea for a few years. I expressed amazement at the famously ageless Krzyzewski. “What?! Coach K fought in the Korean War? How the hell old is that guy, anyway?” Knight looked at me like I was an idiot. “Well Korea’s been there for hundreds of years,” he growled. “Just because he went there doesn’t mean he went there during the war!” Then he jabbed me in the ribs with the butt of his fly rod. He leaned back and indulged in a satisfied smirk, then continued. “Just when I was beginning to think you weren’t as stupid as I originally thought.”

Next I asked him what he was reading, and it turned out to be a lot. One book by John Grisham, another about the Civil War, and a third on D-Day. I couldn’t help but needle him about a famous quip that limns out pretty clearly his thoughts on writers. “You know, for a guy that said most people learn how to write by second grade and then move on to greater things, you sure read a lot,” I said. Knight paused, his eyes twinkled as he bit his lower lip.

“Yeah. I may have said that at one time or another.”

Dragon

Spurred on by his reading interests, we began talking about D-Day. I asked if he could name the beaches. “Sword, Gold, Utah,” he rattled off, before losing the others.

“Juno,” I offered.

“Juno! Good one! What’s the last, though?”

“C’mon man, you know this one. It’s the easy one.”

Knight shook his head, perplexed.

“Omaha!”

“Nah, that’s not it.”

“Yes it is man, that was the beach. The heaviest fighting, Saving Private Ryan and all that.”

“No, mm-mm, that’s not it. It’s not Omaha.”

Then he said something as Eagle Eye Fred fired up the engine to move us somewhere else, but I lost it in the wind.

“What did you say?” I shouted, my hand cupping my mouth.

“I’m not repeating it, you shoulda been listening.”

“The wind was blowing!”

“Well, anyone can listen when the wind’s not blowing!”

As we buzzed over the clear blues and soapy greens of the Bimini flats, Knight went back to World War II, expressing amazement that the Germans did such horrible things under the guise of following orders.

I asked him if he was familiar with the psychologist Stanley Milgram, and his theories on the authoritarian personality, which typically shows great respect and even blind obedience to authority but can be demanding, even cruel, toward subordinates. I was drawing a not-so-subtle line for the famous disciplinarian, if I’m being honest.

“Never heard of him,” Knight parried. “And if you ask me, most psychologists need psychologists.”

The conversation went on as we wove our way through the canals that lace the inner Bimini mangrove forests like so many capillaries. It’s really beautiful in there. Twenty-foot-wide passageways twist and turn through the thick green leaves, and the water is as clear as the air. I got out my GoPro and started filming the scenery as the conversation between Knight and I jumped through centuries of military history, with Knight deftly recounting strategies and battles from Pickett’s Charge to Pointe du Hoc. I turned the camera around on us to record the conversation, because the scene was just so surreal and interesting.

But the topic veered quickly, as it often does with Knight, and soon he was no longer talking about military history but instead about something rather personal to him. It was true insight—honest and searching. And it was sensitive. I glanced at the camera in my hand two feet in front of our faces. A thought flickered across my brain. Does he know I’m recording this?

Five seconds later, Knight stopped abruptly and leaned his whole huge body over mine. “Are you f**king recording this!”

This was not Bobby Knight busting my balls. This was Bobby Knight being capital “F” Furious. He lit into me, eyes blazing, curses flying. “I don’t like you people, the media,” he roared. “I never know what you’re up to! And I don’t like being around ya!” (Incredibly awkward in retrospect, since we were in a tiny boat out in the middle of the water with a man named Eagle Eye Fred standing three feet behind us pretending he didn’t know what was going on—but I digress.)

I’d like to pretend that I was coolly detached and writerly as Knight fumed at me out on those flats. But that wouldn’t be the whole truth. I’m a 33-year-old man, grown in full. I pride myself on my physicality. I was an all-state linebacker in high school, I’ve eulogized my father, and I can tell you what it’s like to watch the sunrise from behind the bars of a Mexican prison. But in that moment, as Knight sat there lighting the world on fire, I felt as if I were 8 years old.

And the worst part was I knew I was in the wrong. The camera hadn’t exactly been hidden—far from it actually, it was quite literally right under our noses—but I also should have been more clear that I was recording once he veered into the personal stuff. So I removed my sunglasses, looked him in the eye, and offered my most sincere apology.

Knight wasn’t having it.

He shut down for almost a full hour and didn’t say a word to me. He slapped at the water with his line occasionally, but the little bonefish ran away as fast as they could. He cursed more, he grumbled a lot. But mostly he was silent. I stared longingly at the shore. The sun blazed down on both of us.

Eagle Eye Fred received a call. The photographer wanted us to rendezvous with Apte and Havlicek for pictures. We turned the boat around, and as the engines started up, I decided to throw up a prayer, trying to rekindle a dialogue. “Hey,” I said to him, “You still only have six of your eight guys picked out for your all-time team.”

Knight just looked over at me coldly, then down at his fingernails. Then he folded his arms and ducked his head into the wind.

After we took the pictures, we headed back to the same place to keep fishing. As the boat slowed to a halt I knew I had to apologize again. This time Knight was ever so slightly more accepting, if not exactly open to the possibility of a future friendship.

“You know,” he said, “I’m sure your mother taught you not to videotape people when they don’t know they’re being recorded.”

I was over the whole thing and not particularly tickled that he brought my mother into it. “I’m sure my mother never taught me anything about videotape etiquette, Bob,” I shot back.

“Well … it’s impolite.”

Another half hour grinded by in hot silence. I was focused on how the hell I was going to write this story after the main subject had stopped talking to me after a day and a half. And that’s when Knight shifted in his chair, cleared his throat, and reached out to pat my back avuncularly. “You know,” he paused, releasing a slow, controlled exhale. “I think you were right about Omaha Beach.”

And we were back in business. Soon he was regaling me about that incident down in Puerto Rico when he may or may not have assaulted a police officer. “I never punched that guy!” He cackled. “You shoulda seen him in the courtroom, he said I took four crow hops and wound up and punched him in his face! No such thing happened! We were in the locker room and he was being rude to Krzyzewski, and I came over and I was trying to separate the two of them, and all I did to that cop was this!” And with that Bobby Knight started mooshing the side of my head with an open hand, pushing me away from him with force. “Open-handed! It wasn’t a punch!”

And all I could do was laugh.

Shortly after that, Knight finally caught a fish. It was the barracuda that had been chasing his bones all day. It turns out barracuda aren’t afraid of Bob Knight.

Oh and by the way, that portion of the video with the sensitive stuff on it? It’s as gone as yesterday’s wind, and as for what was on it, I’ll never tell …

Fuzzy Navel

Back at the Big Game Club we sat at our table and sipped cold Kaliks. Everyone except for Knight, who ordered another iced tea. Havlicek had seen enough. “Hey!” the giant old man yelled, flagging down the waitress from halfway across the room. “Get that guy a fuzzy navel!” He shouted again, pointing at Knight with such enthusiasm that he lifted out of his seat. “Peach schnapps and orange juice!”

It turns out even Generals have to take orders from somebody.

My mind was blown. I had Knight pegged for a whiskey and beer guy before I met him. And then when he said he didn’t drink, it was understandable. But fuzzy freaking navels? The happy hour nectar of blue-haired, little old ladies from Tampa Bay to Cape May? This was too much. “You drink fuzzy navels?” I asked, in evident surprise.

“Ohhh, every now and again I’ll enjoy one,” he responded, evenly.

But just as the drink arrived, one of the Big Game officials brought over a young Bahamian woman whom he had told Knight about earlier. She was a huge basketball fan, and her husband, a coach himself, was in the hospital. Knight pushed away from the table and pulled her up a chair. He spoke to her quietly all the way until his meal arrived.

The ice cubes in his drink melted slowly at the table. I’m not even sure he touched it.

Fake Life

This is how I wanted this story to end.

On the third and final day of fishing, Knight had still been getting skunked. But he’s been dialing in his cast. Working on not slapping at the water, and scaring all the fish away. In time, Knight has developed the tact he requires to not come off as such a bully all the time, to fish and people. And as he stands on the bow of the skiff, the yellow Bimini sun bouncing brilliantly off his white hat and playing in the ripples of the impossibly gorgeous water, he lofts one perfect cast just as the guide had implored and drops his fly ever so gently right on the nose of a nice, big bonefish. And instead of running, the fish chases the lure and bites, and Knight reels it in, smiling all the way. Fin.

But that ain’t what happened.

Real Life

On the third and final day of fishing the photographer still didn’t have a shot of Knight with a fish, because there had been no fish. And he was getting antsy. He asked if he could take my spot in the boat with Knight for the morning, and I could meet up in the afternoon, to hop on the boat and finish my story. Sure, great, I’ll go with Havlicek, I had said.

And so I hopped in a skiff with Havlicek and Bimini boatbuilding and fishing legend Ansil Saunders, who at the age of 82 knows these islands perhaps better than anyone on Earth. Away we whirred to the isolated eastern edge of the island, about three miles from the dock. I complimented Saunders on the skiff’s ride as we were going: smooth, fast and quiet.

The water was exceptionally clear on the east side of the island, even for Bimini. And the sharks, as they so often are in the Bahamas, were out in force. I counted five or six dark wedges of muscle below the surface, unmistakable as bull sharks. Havlicek and I laughed, No fish here! Don’t fall overboard! Ha ha ha ha ha.

Havlicek goes by Hondo to his fans. And Hondo doesn’t fly fish. The guy is perma-chill—cool and quiet and calm. When he likes something you’ve said, which is often, he does this slow, squinty-eyed, open-mouthed smile that conveys pure and utter delight with the thing. It occurred to me at multiple moments that his grandkids must adore him. In fact, other peoples’ grandkids probably adore him, too. He explained to me why he doesn’t fly fish very often as Ansil threaded the hook on his spinning reel through the belly of a small crab. “I don’t like to be whipping that thing around on a small boat.” He pantomimed fly-casting. “Might hook somebody.” Saunders let the crab go, and it dangled over the crystal water, snapping its tiny claws futilely. “Me,” Havlicek continued, “I’m just here to catch fish.” At that a huge smile slowly unfurled across his face.

And he did catch fish, a few anyway, but not too many. And soon Saunders decided we had better go find more fish, and get me closer to Knight’s boat so we could make the trade. We started running again, but something was different. The trim was off, the bow too high. And the engine sounded somehow different. I didn’t think much of it at first.

But soon Saunders was shouting something over the wind in his stew-thick patois. “Ho’o in dee bo’! Ho’o in dee bo’! Ho! In! Dee! Bo’!” Initially I couldn’t tell what he was saying. But then it dawned on me.

I whipped around.

“Are you saying there’s a f**king hole in the boat?!”

Saunders was ankle deep in water, with an apologetic look on his face. “Should I come back and bail?” I shouted over the wind. Using a lot of hand signals he told me that if I went back to where he was, the boat would sink stern first, and that the best way to keep it afloat would be to run it as fast as he could back to the harbor. Which is what we did.

And this part still feels like a fever dream. Because now John Havlicek and I are sitting in lawn chairs in the bow of Ansil Saunders’ boat, while it’s sinking in shark-infested waters, and we start to carve our way through the mangrove forests again. And it’s jungle as far as the eye can see, nothing but bony fists of mangrove.

And then I look to my right, and there in the middle of the forest is a life-size bust of Martin Luther King.

We were passing the legendary Healing Hole, where King—perhaps apocryphally, but perhaps not—conjured up his “I Have a Dream” speech. A preconscious thought fluttered through my head. I’d like to stop and see this. But then I remembered we had more pressing holes to worry about.

As we burst into the channel, I looked down and realized the water had crept to the bow, and I picked up my and Havlicek’s bags to put them somewhere dry. Now the boat was running very low in the water, so low the water was threatening to come spilling in over the bow, swamping us in the deep channel. Havlicek and I had been laughing at the absurdity of it all, but at that point, we stopped. The harbor was still a good three quarters of a mile away, and we weren’t going to make it more than a few hundred yards.

We ended up beaching the boat near Saunders’ work shed. Havlicek and I unloaded our stuff and climbed onto the sand. For his part, Saunders hopped nimbly out of the skiff and stuck his fingers in his mouth, whistling loudly. To our surprise, one of the most sunworn and bedraggled islanders—nay, humans—I’ve ever seen popped out of the bushes as if he had been waiting there for us, and in retrospect, perhaps he had. The man had long, dusty dreads, shredded pants and skin like walrus hide. Barefoot, he shambled over and looked at the boat for a long while with his chin in hand, then crouched down and started to inspect the damage more closely.

Havlicek and I eventually started walking back to the hotel, but I knew he had bad knees, so after some protest from him, I stuck out my thumb and hitched a ride with two Biminian basketball fans who were all too happy to give the great Hondo a lift. When we got back to the Big Game Club, Havlicek, who had been mostly silent throughout the ordeal, turned to me wide-eyed. “Did you see that guy who popped out of the bushes?”

Overtime

The rest of my day was spent on the docks, waiting for Knight to return. There was no word on whether he caught a fish. As the afternoon burned into the early evening, I went upstairs to the picturesque deck attached to the bar, which overlooks the Bimini channel. A PR man for our hotel and one of Knight’s handlers huddled nervously at a high table, glancing over their shoulders from time to time, clearly very anxious about the old man’s return. I pulled up a chair. Scuttlebutt was that Knight hadn’t caught a fish. He had a bone on the line, but one of those knots he had been so worried about, well—it apparently had slipped. Eek. The fish swam free. Allow me to surmise the general sentiment at the table: Would Coach be pissed off? Of course he’d be pissed off! Three days fishing in the hot sun and no fish? Not to mention the long flight. This is bad. This is so bad.

Five o’clock rolled around a bit early, as it does in the Bahamas, and the waiter came by to take our drink orders. The handler abstained, clearly stoning himself for the bad things to come. The PR man ordered a piña colada, choosing to stone himself in a different way. I ordered a Kalik. Knight’s boat came in shortly, and after showering, he came to the bar to join us—ambling slowly, head down, hands in his pockets. We watched in anticipatory silence as he made his approach. Then he looked up and sternly surveyed the table. When he saw the piña colada his eyes lit up. “Oh a piña colada! That looks good!” he crowed. “Miss,” he said, lightly reaching for one of the passing waitresses, “I would like a piña colada, please.”

Havlicek and Apte joined us in the meantime, each ordering beers. With the ice broken a bit, the PR man ventured a hopeful question. “So uh, Bob, no fish, but did you have fun, anyway?” Knight let the question hang there for a moment. Then he leaned forward and took a deep sip from the frosty concoction in front of him. Finally he looked up. “Of course I did! Hell if you can’t have fun fishing without catching any fish, you just can’t have any fun, period.”

Then he took another long sip and leaned back in his chair with a contented sigh. “Hey, have I told you guys about the time me and Ted Williams were trout fishing the Kamchatka Peninsula in Siberia and we were crammed in this little, single-engine airplane and Ted, he turns to me and says …” Soon the whole table was laughing.

Bob Knight didn’t smirk much that evening. But he did smile.

This article originally appeared in the Summer 2015 issue of Anglers Journal.

Originally Appeared on GQ