The Bob Marley Story ‘One Love’ Leaves Out

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Chiabella James/Paramount Pictures

February is Reggae Month in Jamaica, and the same week that the Bob Marley biopic One Love broke box office records, signs of Marley’s enduring legacy are everywhere you look in Kingston. At the annual Island Music Conference, keynote speaker Wyclef Jean (who updated Marley’s “No Woman No Cry” for the ‘90s on The Fugees’ classic album The Score) exhorts an audience of young Caribbean creatives to look to Marley’s deep catalog of songs as a model for building generational wealth. Just uptown, rising star Naomi Cowan (who portrays reggae singer Marcia Griffiths in One Love) hosts and headlines a woman-centered live showcase at the Dubwise Cafe. Naomi’s father Tommy Cowan, a reggae star in his own right, also produced the 1978 One Love Peace Concert which gives the movie its finale.

Two nights later, Naomi Cowan’s onscreen bandmate Sevana (who plays fellow I-Threes member Judy Mowatt) joins the bill at the Lost In Time festival at Hope Gardens on the city’s outskirts. The routes to all these destinations are lined with hand painted signs announcing an upcoming birthday tribute for grandson Jo Mersa Marley, who passed away unexpectedly in 2022, while the speakers in every other Uber play “Praise Jah In The Moonlight,” a viral TikTok hit by YG Marley (the son of Rohan Marley and Lauryn Hill) which samples Bob’s 1978 song “Crisis.”

Even as the movie, directed by Reinaldo Green, introduces Marley to generations born long after his passing, global pop culture is still shaped by the events it depicts. Which means this retelling of Marley’s story is right on time—but it has some heavy lifting to do, because it’s likely to shape how a generation of viewers understands Marley’s story going forward.

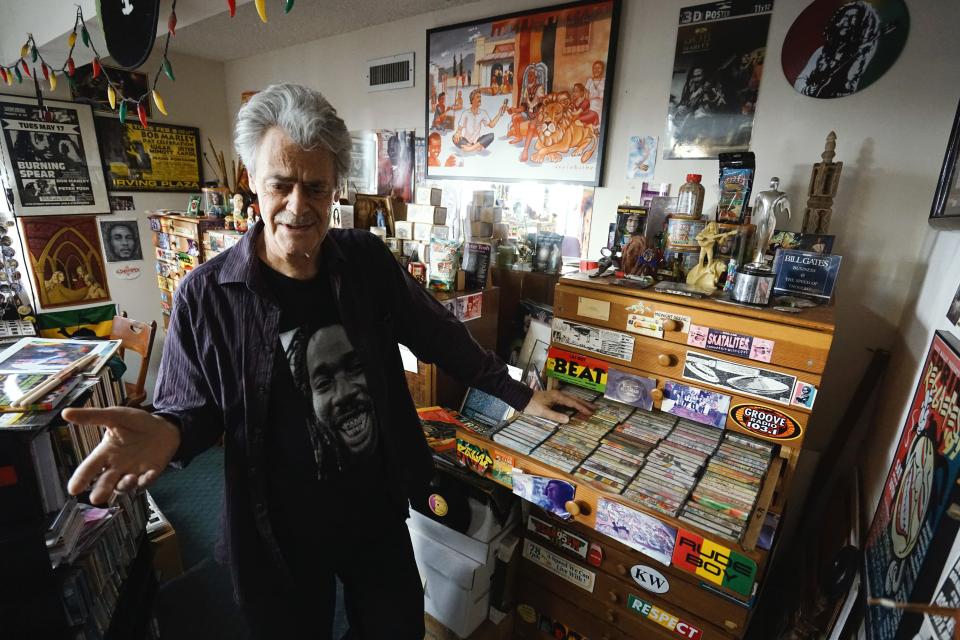

“My friend Matt Jensen has been teaching a course in Bob Marley at the Berklee College of Music up in Boston for 20 years now,” says Marley historian Roger Steffens, speaking via Zoom from his home in L.A., where his personal archive of Marley relics has now taken over 7 full rooms. “[Jensen] told me that in the past year or two, the students come in not really knowing much at all about Bob Marley. In the past, they've all come with Marley baggage but wanting to learn a whole lot more. Now it's just a tabula rasa. Who is this guy? Why should we care?”

One Love has done a powerful job of making a new generation care. But it’s still (by necessity) an abridged version of Marley’s inspiring struggle against the powers that be, combining characters and glossing over some of the details––many which are so dramatic you could hardly put them in a believable movie. As Steffens, who was also the curator and guide of a recent pop-up museum in L.A. called the One Love Experience, puts it, the film “has taken various elements of Bob's life and shuffled them together like a deck of cards,” in order to lay out a story that flows onscreen.

As perhaps it should. “You’re allowed to do things like that in a movie, to tell the story,” Wayne “Native Wayne” Jobson, another attendee at the Island Music Conference, tells me. “If you want facts, watch a documentary!” Jobson should know. His cousins Diane and Dickie Jobson worked as Bob’s lawyer and label manager, respectively; Wayne himself is a key voice in the Netflix documentary Remastered: Who Shot The Sheriff?, the most detailed exploration to date of the 1976 assassination attempt on Bob at his home at 56 Hope Road, which figures significantly in One Love.

Of course, you’d have to watch many documentaries (and read many, many books) to get close to a true history of One Love, so to rise to the challenge of this teachable moment, we’ve watched and read them for you. More importantly, GQ sat down with Steffens, Jobson, Cowan and others with firsthand perspective on both the film and its raw material to separate the mythic Marley image from the even more epic truths.

Roger Steffens: Bob Marley Scholar

Ambush In The Night

The event that sets in motion both the action and ethical dilemmas of One Love is the shooting of Bob, his wife Rita and manager Don Taylor at his home and studio on December 3rd, 1976, days before Marley was to appear at the politically loaded Smile Jamaica concert. The filmic version hews close to the version of the attack Don Taylor recounts in his 1994 memoir Marley & Me, in which he suggests that he blocked bullets meant for Bob with his own body as he reached to take a slice of grapefruit from his hands. “I took six bullets for you!” Taylor’s character shouts at Kingsley Ben-Adir (who portrays Marley) during one memorable scene in the film.

“Well, he took five, not six,” Steffens says. In the film, Taylor jumps up from his chair in front of Bob when the shooting starts, but as Steffens points out, “If you’ve been in the kitchen at 56 Hope, there’s no place for him to sit there. You come in the back door and it's like a closet, almost.”

Many sequences in One Love were shot on location at the sites where real-life events occurred, particularly in Jamaica, but since the original house at 56 Hope Road is now a museum, the filmmakers had to recreate it. “They built it exactly like 56 Hope,” says Wayne Jobson, who visited the film set during production and gave Green input along the way. It cost $400,000 dollars just for the facade–but it wasn't just the facade; same rooms and everything. I walked in there and it was spooky. [I felt like] I was in Hope Road in 1973.”

Approaching the tall, narrow back door of the real 56 Hope house is an undeniably spooky experience. Neither the Marley memorabilia now covering the walls or the chattering murmuration of a tour group of fellow museum visitors can dispel the aura of dread that lingers there. The gaping bullet holes that pockmarked the wall that fateful night are still visible opposite the back door, behind squares of plexiglass. As Steffens suggested, the tiny kitchen at the top of the garden stairs is indeed a claustrophobic space, more of a pantry or a passageway than anything else, and it’s hard to imagine anyone having much room to move when intruders burst in—especially considering there were others present, including Bob’s personal chef Gilly and a member of the Marley entourage named Louis Simpson (or Griffiths, in some sources) who took a bullet in the torso.

In an interview he gave in 1979 as part of a documentary film made during Marley’s visit to New Zealand, Don Taylor himself confirmed that there was no time and no space to move or react at all to the sudden gunfire. The fact that all four victims survived—including Rita Marley, who was shot in her car as the gunmen approached the rear of the property—is a small miracle, and certainly contributed to Marley’s mythic status, now and then. “They were just sloppy,” observes Steffens. “Sloppy. Which argues against the idea of the CIA being in any way involved, because they wouldn't leave ‘til they were absolutely sure they'd got their man.”

Bob Marley at home, Kingston Jamaica

JAMAICA-BOB MARLEY MUSEUM

Rat Race

Rumors of CIA involvement in the attempted hit at 56 Hope have swirled since the ‘70s, and government documents procured by Marley biographer Timothy White for the expanded editions of his widely read book Catch A Fire, confirm that the agency was keeping tabs on Marley, alarmed by his popular appeal and openly revolutionary stance. Though unidentified, the shooters’ motivation and political affiliation quickly became an open secret. Claudie Massop, a gunman for Jamaica’s conservative JLP party and a friend of Bob’s, attempted to call Marley from jail to warn him of an impending attack by a faction of his own Tivoli Gardens-based crew of gunmen. That faction was led by Lester Lloyd Coke, aka Jim Brown, who would go on to even greater notoriety as the leader of the Shower Posse, before perishing in a jail cell fire in Kingston’s General Penitentiary while awaiting extradition to the US on drug trafficking charges in 1992.

In 1976, however, these JLP partisans objected to Marley’s plan to headline the Smile Jamaica concert, scheduled for December 5th, just two days after the shooting and less than two weeks before Prime Minister Michael Manley—head of the left leaning PNP and the JLP’s bitter rival for power—called for a snap election, effectively using Marley as a political trophy. Marley’s friendship with Massop had provided him some cover until then, and in multiple conversations reported in Vivien Goldman’s 2006 book on the making of the Exodus album, Massop swore that if he had not been incarcerated at the time, the shooting “never coulda happen.”

Theories of a larger conspiracy were given a boost by one of those stranger-than-fiction details of the event that jumps out from the Who Shot The Sheriff documentary: As Marley prepared to perform at Smile Jamaica despite the clear and present danger to his life, one of the people around him was Carl Colby—son of former CIA director William Colby. Colby was present as part of an American film crew tasked with documenting the concert for Island records. Yet, after decades of examination of this connection from every angle by various investigators and historians, “Colby junior appears to have been an innocent cameraman,” as Goldman puts it.

Exodus

One Love’s recreation of Smile Jamaica is brief but memorable. It’s impossible not to feel a surge of emotion at the opening chords of “War”—a battle song adapted from a speech by the Ethiopian Emperor Haile Sellasie, a divine figure to Rastas like Bob. When I catch the film at a theater in Kingston’s Sovereign Centre mall, the audience chants along with the words and claps at the crescendo, momentarily forgetting it’s not a live concert.

An acapella rendition of the Marley lyric “Puss an’ dog they get together/What’s wrong with loving one another?” (from “So Jah Seh,” the noodly 10-minute jam which ended the real-life concert) becomes a sort of chorus for the movie’s themes. It also underscores that music is the real star here, and the movie wastes no time following Marley and his band into exile in London, recreating the conditions under which his critically-praised Exodus album was recorded.

Some songs from Exodus, however, were already being written before the shooting at Hope Road, including “Guiltiness” and “Is This Love,” which were composed around the same time as the Kingston sessions for the song “Smile Jamaica,” recorded to coincide with the concert. The film’s depiction of the Exodus sessions also skips over a crucial period of several weeks that Marley and bandmates spent in the Bahamas at another Blackwell compound, a property called—true story!—“Seapussy.”

Blackwell would later build a studio in the Bahamas and record everyone from Grace Jones and the Tom Tom Club to James Brown himself there, backed by his crack house band, the Compass Point All-Stars. But in 1976-77 there was no such studio, so according to Goldman’s book, bassist and bandleader Aston “Family Man” Barrett had to string up mics around Seapussy’s open-plan living room to capture the acoustic and percussion jam sessions in which the songs were developed. According to Neville Garrick—Bob’s cover artist and right-hand man, portrayed in the film by Jamaican actor and dub poet Sheldon Shepherd—Marley and his band worked on the Exodus tracks “Waiting in Vain,” “Turn Your Lights Down Low” and “Three Little Birds” in these sessions. They also workshopped early versions of songs that would find their way onto Marley’s later albums, including “Time Will Tell” (Kaya, 1978) and a lyrical account of the Hope Road shooting called “Never Go Down”—which ultimately saw release on the Survival LP under the title “Ambush In The Night.”

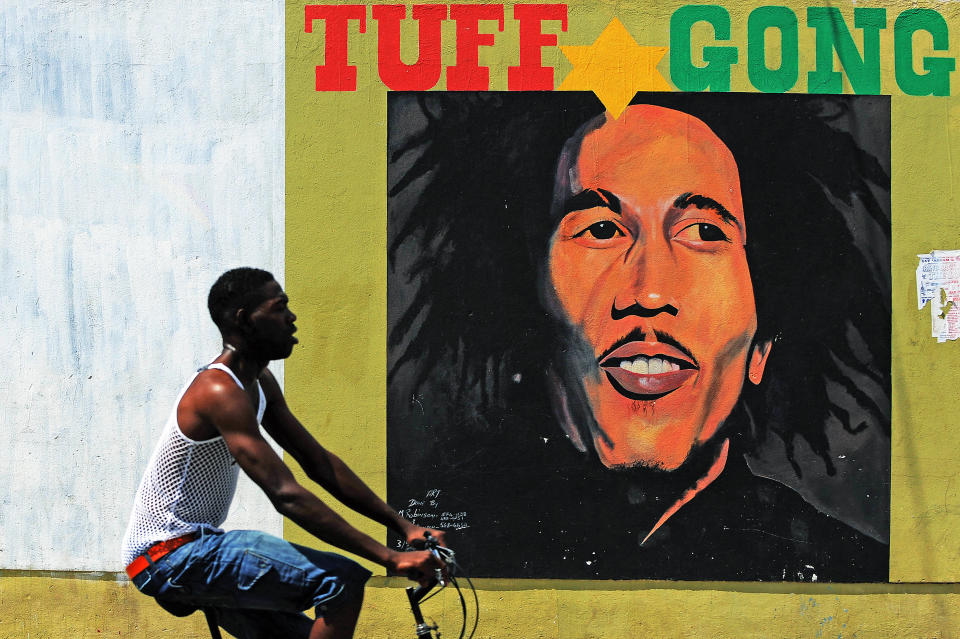

A man walks past a mural of late musicia

A man pedals past a mural of late musici

A vendor pulls his cart in front of a mu

One Love

It was during his time in London that Bob decided to throw his weight and star power behind a grassroots movement to get political “puss an’ dog” to live together in a Kingston ripped apart by the kind of partisan violence he had just experienced firsthand. It was an incredible moment in Jamaica’s history that is remembered as the Peace Treaty of 1978. Most incredible of all, it was initiated by the gunmen themselves. Massop and another “Ranking Dread” named Bucky Marshall—top gunmen for the JLP and PNP, respectively—made this bold decision to defy Jamaica’s political bosses while in jail together. “Manley put them in the same cell,” laughs Steffens. “Instead of beating each other to death, which is what Manley probably was hoping would happen, they started comparing notes, and they realized they were both being played for suckers by the topanorises [snobs] up in the hills. They declared a truce between themselves in that jail cell before they were let out.”

The film shows Bob being approached by Claudie and Bucky in a London park, but underplays the extent of the grassroots peace movement, as well as the centrality of Marley’s role in it. “Bob flew them out!” observes Steffens. “It wasn’t just Oh, you’re waiting to talk to me in this park. Bob paid for their plane fare to England. They were calling him all the time—y’know, We want to make you come home and feel safe. And he didn't—'cause at least one of those guys was close to the attempted killers. It took a lot of persuading to get Bob to come back to Jamaica. [The peace negotiations] lasted a long time—during which time Bob was paying for their place to live and their tickets to and from.”

Similarly, the scene in which Bob takes confession from one of the shooters and absolves him is an editorialized version of a real event. In the film, this encounter takes place at Hope Road itself, bullet holes in full view. But according to Steffens, the sequence is based “on something that happened in Europe on the ‘77 tour. Somebody went backstage and said [to Marley], I was supposed to be part of that crew that night, but I couldn't find my gun. Bob not only forgave him on the spot, but invited him to travel on the rest of the European tour with him.”

Taylor’s book gives us a much less forgiving Bob. In Marley & Me, he writes that on a Wednesday afternoon in June 1978, “Claudie [Massop]’s right-hand men led us to a lonely spot near the McGregor Gully” in Kingston to be “witnesses for the prosecution” in a ghetto trial of the three of the four shooters from the attack at 56 Hope. According to Taylor, these men were executed by Massop’s men after he and Marley positively identified them. There are several reasons to take Taylor’s account with a grain of salt, however. For one thing, there’s no reason to think he or Marley would have seen all the gunmen. He also states that these shooters confessed to being paid by the CIA for the hit with “guns and unlimited supplies of cocaine,” a scenario that doesn’t fit well with the other known facts. Conveniently, he concludes that he and Marley “never mentioned that day again. It was as if that Judgement Wednesday had never happened.”

This was not the only case in which doubts have been cast on Taylor’s account—or his accounting. In the film, Marley’s character confronts Taylor over money he was siphoning off from African promoters, giving him a beatdown in front of other band members while they are in exile in Europe. This confrontation, too, seems to be based on real events, most infamously an episode in which Bob and his friend Alan “Skilly” Cole interrogated Taylor about missing funds during the 1978 Africa tour itself, supposedly even dangling him off the balcony of a hotel room in Gabon to extract a confession. Taylor also recounts that Bob later attempted to force him to sign paperwork relinquishing him from their contract at gunpoint in Marley’s Miami home.

Top Ranking

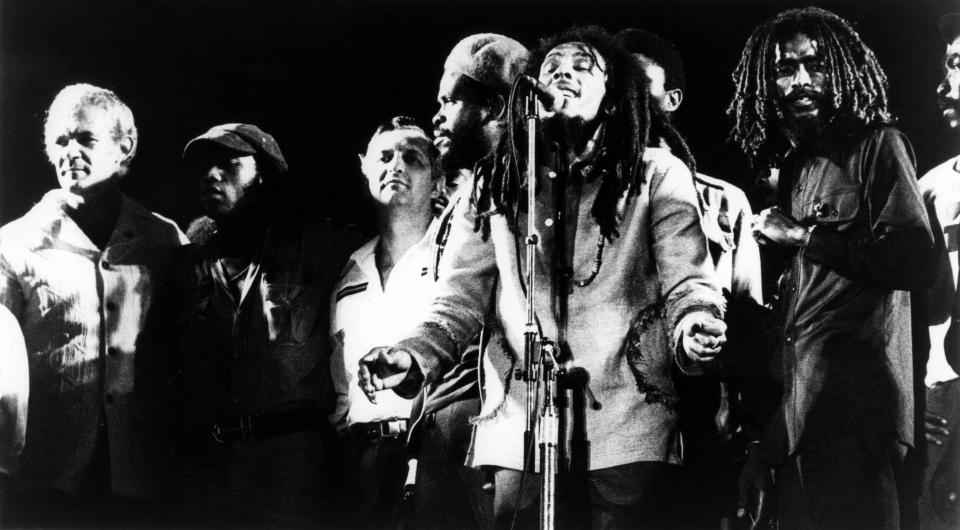

If all these anecdotes paint a picture of a Marley much tougher than his often saintly media persona suggests, it’s important to recall that it was his ability to stand toe to toe with Kingston’s baddest gangsters that allowed Bob to guarantee the Peace Treaty at street level. Working with the likes of Massop and Marshall ensured that the generals in Kingston’s street war were on board with the idea of unity. Bob’s headlining performance at the One Love Peace concert made this peace visible and official. In a now-iconic image Marley even called the heads of the two rival parties—the PNP’s Michael Manley and the JLP’s Edward Seaga—onstage at the height of his set, inducing these bitter enemies to clasp hands with the power of music. Green chose, perhaps wisely, not to restage this image, instead allowing an archival photo of the real event to speak for itself during the film’s closing credits.

Photo of WAILERS and Bob MARLEY

The Peace Treaty of 1978 was short-lived. In February 1979, Massop was shot over 40 times by Kingston police. Bucky Marshall fled to Canada but in March 1980 he too was murdered in a New York nightclub. By the time the next election was called, in October of that year, partisan violence had spiked to new highs. But in addition to providing a shining example of what grassroots unity could mean for Jamaica, the Peace Treaty shaped the evolution of music in ways that are still just being understood, as artists and sound systems began playing in parts of the city that were previously off-limits, speeding up the spread of new trends in reggae—including the sound known as dancehall.

The most prominent “Ranking Dread” to survive the end of the treaty was a don named Milton “Red Tony” Welsh, an associate of Bob’s who controlled the PNP stronghold of Arnett Gardens, otherwise known by the nickname Marley famously called it in song—“Concrete Jungle.” Tony Welsh (no relation to the British actor of the same name who portrays Don Taylor in the film) owned a sound system in West Kingston called Socialist Roots, or sometimes just Papa Roots. Papa Roots featured some of the greatest live deejays of the era, alongside pioneering selectors like Danny Dread, who is something like the Kool Herc of dancehall, mixing the music underneath the voice of dancehall deejays in ways that would be imitated across the island.

These days, Danny Dread can be found sitting under the shade tree in the front yard of his house in the Vineyard Town section of Kingston. In an eerie echo of 1976, the sitting government—the JLP, this time—called for snap elections mere days after One Love’s Jamaican premiere, and now the neighborhoods between New Kingston and Vineyard Town are lined with Orange or Green flags denoting their political affiliation. Though semi-retired from the music business, Danny can still clearly recall the days when Bob and Tony Welsh navigated these same lanes to attend Papa Roots street dances, delivering pre-releases of Marley’s newest music on acetate discs.

“Tony Welch was like him bodyguard—he used to move around with him after Bob get shot,” explains Danny, who is a devout Rasta. “Just like Bob know Massop, too. One run Tivoli and one run Jungle. Bob and me get to talk and reason when Bob cut a tune to come give me named ‘War’”—the very same song with which Bob opened his set at Smile Jamaica. “I know His Majesty speak that, so that tune very important to me, yunno. And there ‘pon the back of the disco plate you have another tune named “Want More.”

After the end of the treaty, Welsh still kept Papa Roots sessions going at a place called Angola Lawn in Avon Park Crescent. “Every year Tony Welch did keep a dance there,” recalls Danny. “Free, too! Everybody can come in free, so the dance always rammed. Bob come there one a them time, too.” Inspired by Marley’s presence, Danny would emphasize the rhythm of Marley’s song “One Drop” (from the Survival LP) by dropping the thunderous bass in on just the drum hits, manually cutting power to the tube amps in time with the music. This “one drop” style of mixing would become his trademark—and when imitated by the studio bands of producer Henry Junjo Lawes, it would also become the signature sound of reggae played “in a dancehall style.”

Danny and his fellow selectors would build on this innovation in the 1980s, chopping a new wave of digital reggae rhythms into faster, more staccato patterns until arriving at the distinctive boof-boof-kaff kick-and-snare pattern which characterized ‘90s dancehall. This instantly recognizable pattern—which can be heard to this day, underpinning everything from Bad Bunny and Drake’s “Mia” to Ed Sheeran’s “Shape Of You”—is linked directly to Marley’s influence via Danny Dread’s creative touch with a mixing board.

Redemption Song

The melody of Marley’s most famous tune provides an inspiring score for the movie’s major events and scenes in One Love show Marley composing “Redemption Song” on acoustic guitar in the garden at Hope Road. In flashbacks, it's even suggested that he wrote a version of it while still a teenager. In reality, the first confirmed version of “Redemption Song” is from a 1979 tape known as the Dada Demos. Marley recorded “Redemption Song” in two takes with a full band, but couldn't land on an arrangement he was happy with. It was Chris Blackwell who suggested he record it as a spare acoustic rendition of just voice and guitar (as Blackwell recounts in his 2022 memoir The Islander). It was the last song Marley recorded.

The film takes poetic license with other events in order to get the power of Marley’s story across. For example, Marley’s absentee white father is depicted as Bob imagined him; a uniformed, pith-helmeted English army officer on horseback. Steffens’ conversations with family members who have researched the Marley bloodline refute this, suggesting that Norval Marley was an unstable drifter who was neither born in England nor a military officer. Rather, his only attachment to the army was as a “ferrocement engineer” in the Labour Corps.

Likewise, Studio One label head Clement “Coxsone” Dodd, an early mentor and father figure to Bob, first appears on screen chasing another musician out of his studio at gunpoint. He then brandishes the pistol in the face of the young Wailers, Bob’s ska trio with Bunny Wailer and Peter Tosh. This event is nothing like The Wailers’ first few sessions with Dodd—which produced the hit “Simmer Down” among other classics. In sketching the hardscrabble business of early Kingston studios, the film seems to have created a composite of Dodd and his main rival at the time, Treasure Isle label head Duke Reid, an ex-policeman who always carried a pistol and was known to fire a single shot in the air when his band nailed a song in one take–arguably the beginning of the long and venerable Jamaican tradition of “licking shots” to salute musical excellence.

Most of these narrative amendments serve to center the film's powerful themes, framing the movie’s Bob as a man on a mission. “For all the folks involved with Bob Marley and the Wailers at that time it was more about a spiritual mission,” says Naomi Cowan, whose father Tommy Cowan was the music director for the One Love Peace concert. “They had to spread the music and the message.” Cowan’s father was so involved in Marley’s career that before the shooting he also received threats, and was forced to move with his family (including Naomi’s older siblings) into the Pegasus hotel for safety. “He always just reminded me of how serious everyone took their jobs,” Naomi Cowan says. “They all recognized that this was a moment in time for them to spread the message of reggae music and the message of love–and how recreating it now is also important. He didn’t focus on the drama,” she concludes. “He focused on the purpose.”

Steffens echoes these sentiments. “This is a movie that is now more necessary than at any other time,” he says. “The world is on the brink of utter disaster, and it is only that philosophy that Bob has promulgated that's going to bring us out of it.”

Jobson sums it up this way: “You know, the movie One Love beat for #1 spot opening weekend was supposed to be a superhero movie. But the real superhero is Bob Marley.”

Originally Appeared on GQ