Boat of the Week: Why This 50-Foot Hybrid Cruiser Could Change Boating as We Know It

Going to the northernmost human settlement on Earth to do a boat test, just a few hundred miles from the North Pole, sounds like overkill. Unless you’re testing a boat-and-engine package that could move sustainable yachting forward in a serious way over the next five years.

Plus, how can you turn down a test on a boat named Kvitbjørn—translated from Norwegian to polar bear—in some of the most beautiful and remote waters in the world?

More from Robb Report

Who Says Volvos Are Boring? This Sporty P1800 Restomod Will Star at Monterey Car Week

First Drive: Ferrari's First V-6-Powered Production Car Inhales the Track Like a Beast

Robb Report was one of the first publications invited to test the 50-foot Marell M15, an aluminum-hulled vessel originally designed as a fast-patrol boat to run in Arctic waters, where water temperatures routinely fall to about 28.4 degrees Fahrenheit, or freezing. With its first-of-a-kind hybrid diesel-electric propulsion, Kvitbjørn will be used as a high-end touring vessel to transport guests around the local ice floes and explore the fjords in “silent” mode.

Courtesy Volvo Penta

We’d been warned to bring boots, parkas, balaclavas and battery-heated gloves for the test, since the wind chill had hit 30 below the week before. At the docks in Longyearbyan, Svalbard, the main settlement of the island archipelago in the Arctic Ocean, the other boats had big icicles hanging from the hulls. Being early May, the rest of the world was thawing, but the local tourist outfits were still running snowmobiles and dog-sleds across the white tundra. The fjords around us were white, stunning.

Kvitbjørn had originally been planned to be powered by three to five high-horsepower outboards, which would give it an impressive top end of 55 mph. But then it wouldn’t be the most carbon-efficient boat in an archipelago that has been kept pristine by international treaty to allow its reindeer, sea lions, walruses and polar bears to avoid the environmental degradation of the rest of the planet.

Courtesy Volvo Penta

It’s a magical place, we soon discovered, cruising out from the settlement of about 2,000 into empty waters and the barren landscape. On the edge of a glacier, the ocean had a crystalline formation of ice across the surface, creating a beautiful symmetric pattern. Further in, a wall of sea ice blocked the channel into a fjord, and beyond that, a walrus was sunning itself on land.

Besides reducing carbon emissions, the idea behind the hybrid electric-diesel propulsion was that you can cruise quietly under battery power for hours at a time. That lets the vessel into environmentally sensitive areas.

Courtesy Volvo Penta

“We decided to move away from outboards because of the expectations of our guests, who want the whole journey aboard the boat to be more sustainable,” said Tore Hoem, adventures director at Hurtigruten Svalbard, the tourism company that had commissioned Kvitbjørn—which had, as of just a day earlier, been delivered and was now officially Hoem’s baby.

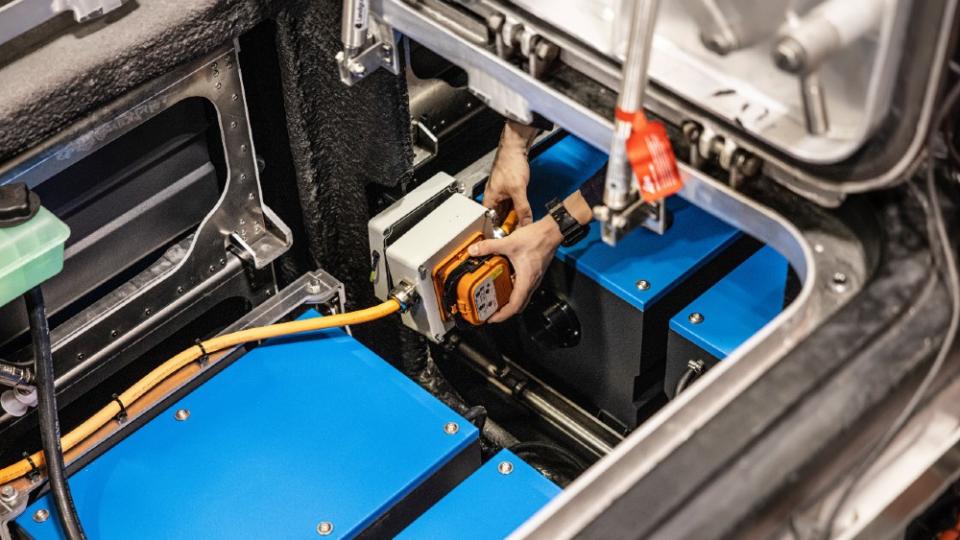

Volvo had worked with Sweden’s Marell Boats to create this first-of-its kind hybrid package, incorporating two D4 33- DPI engines with two 70kW electric motors that were powered by 1000-kW batteries. The hardest task had been to reconfigure the rear part of the boat to make space for the huge batteries. There was also new technology that had to be developed because of the region’s icy waters. The battery compartments, for instance, had to be heated rather than cooled, as they would in warmer climates.

Courtesy Volvo Penta

“If it works here, it will work anywhere,” said Hoem. The new system worked just fine. We spent a few hours heading across the archipelago, then idling around the mouth of the fjord, hoping for a sight of the ever-elusive polar bear. While there are 3,000 in the archipelago, and residents are required by law to carry a rifle outside of town in case they are attacked, although sightings are rare.

When we got closer to land, Hoem switched it into silent mode, which wasn’t exactly silent. The idea is for the boat to run without noise, so guests can enjoy the wilderness without any sign of human intrusion. But the Volvo technicians, who had never heard the boat running in silent mode, were surprised by how loud the gears running the electric motors were. It wasn’t as loud as it would be with the diesels, of course, but it was distracting.

Still, there was nothing like being out in this winter wonderland, a small research vessel being the only other boat in sight, and the tundra just beyond. The sun was out, and with no wind, it felt warm-ish all bundled up outside on the cockpit, though my fingers started to numb in less than a minute when I took off the gloves for pictures. So maybe it wasn’t that warm. But it was an amazing feeling just to be cruising in this wilderness.

Courtesy Volvo Penta

The difference between Kvitbjørn and other diesel-electric propulsion systems aboard other yachts is that this isn’t a one-off. It’s the first of what Volvo expects to be a long line of hybrid vessels that will use its systems—not just the engine/battery combo, but a whole integrated package running from the stern to the helm. The company realizes that the only way to make carbon-reducing propulsion actually work in the real boating world is to integrate the boat’s many functions into one system. That lets the boat owner have one source for repairs and warranties.

It’s a big challenge, but Volvo was first to market with integrated systems like joystick controls and assisted docking, so this new boat could represent the way forward for a boating industry that has lagged behind the electric car industry and even commercial shipping.

“Our real job will be to industrialize the system,” says Johan Inden, president of the Volvo Penta Marine Business Unit, also on board for Kvitbjørn’s initial test run. “Our goal is to be able to scale the hybrid system across all our engines, which run from 13 to 5,400 horsepower.”

Courtesy Volvo Penta

Linden expects the hybrid system to be a standard Volvo offering in three to five years, and that the “tipping point” where hybrid engines will outnumber conventional diesel and gas engines will be 2030. That sounds like a long way off, but it also means that the water will be much greener by then.

In the meantime, tests will continue on Kvitbjørn as Volvo attempts to dial in the new technology. We spent a few more hours cruising the lonely waters, and then headed back to Longyearbyen, where I had a chance to run the boat—though I noticed Tore seemed a little nervous about handing over his new toy. I promised him I wouldn’t break it.

Courtesy AP

Kvitbjørn was a fun ride, largely because there was little I had to do when it came to moving between the traditional and hybrid propulsion. At a certain speed it shifted automatically. The system also had different modes on the helm console that allows the captain to operate the boat at peak efficiency, whether running in silent mode, or spooling up to top end.

The boat will run 1,000 hours—way more than the average private motoryacht—over the six-month season, so Volvo will have plenty of test data to work with. Eventually, the hybrid application could be used on boats from 25-ft. runabouts to 120-ft. yachts, so it would cover the majority of pleasure boats.

Courtesy Volvo Penta

“We plan for this to be the new normal,” says Linden, who expects the system will be a sea change for boating.

Sitting at the Svalbard airport, I got an urgent text from Jennifer Humphrey, Volvo Penta’s vice president of marine marketing, who was out on Kvitbjørn. “Guess what,” it read. “We just saw a polar bear!”

Best of Robb Report

The Chevy C8 Corvette: Everything We Know About the Powerful Mid-Engine Beast

The 15 Best Travel Trailers for Every Kind of Road-Trip Adventure

Sign up for Robb Report's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.