For blind cooks, federal Braille program brings recipes within reach

By this past summer, Sherry Gomes had received in the mail a book of Portuguese recipes and Le Cordon Bleu’s “Classic French Cookbook.” A book of air-fryer recipes was en route, while still other titles had caught her interest: volumes on casseroles, slow cookers, Italian cuisine and holiday cookies; there’s “The Book Lover’s Cookbook” and “The Anne of Green Gables Cookbook.”

“I need a few more bookshelves,” Gomes, a retiree and novelist who is blind, says giddily of the collection - all of it Braille - that’s blooming at her home in Patterson, Calif. It’s an abrupt shift for Gomes, 65, who recently also obtained a dozen or so favorite literary works in Braille, now that an arm of the Library of Congress has brought book ownership within closer reach than ever.

The nearly century-old National Library Service for the Blind and Print Disabled lends audio, large-print and Braille reading materials through a nationwide network of libraries, the Postal Service and via download. But in June 2022, following counterparts in Canada, the United Kingdom and elsewhere, the NLS added a feature: reproducing Braille books and magazines on-demand from its collection. Items are mailed to NLS users - up to five per month, per person - free and to keep. (Technically it’s an indefinite loan.)

Cookbooks have been one of the program’s more popular genres, accounting for nearly 500 of the almost 8,000 requests made as of mid-December. Like other top categories - best-selling fiction, religious texts, books on knitting and crochet - cookbooks tend to be thumbed repeatedly over time.

“We all have things that we refer back to,” says Kristen Fernekes, the NLS’s head of communications, “or when you’re culling your bookshelf you’re thinking, ‘Well I couldn’t possibly get rid of that.’”

The demand for owning a cookbook was expected, she says: Food is universal, it’s social and it’s “a messy prospect.”

Braille cookbooks - and Braille books in general, beyond popular titles and authors - can be difficult to find for purchase or are priced beyond a splurge, some Braille users say. Quality-controlled Braille is expensive to produce, involving transcription into the raised-dot code, proofreading and, for cookbooks, extra formatting. And Braille often requires more pages and thicker paper.

What has changed now, in part, is the growing availability of electronic Braille. Digital files for Braille e-readers, which are devices with pins that move up and down to render refreshable lines of Braille text, can also be sent to a Braille embosser for printing, as the NLS does to fill its on-demand requests. E-Braille files are “an iterative step now in the production of almost any Braille,” Fernekes says. So even as the NLS moves forward - it now offers Braille e-readers on-loan, as costs have eased and as downloads of its roughly 20,000 e-Braille books have spiked in recent years - hard copy Braille moves with it.

So far, the cookbooks requested by users mostly represent a familiar mix: manifestos on fast, slow, few-ingredient, diet-friendly or single-pan/pot/skillet cooking; recipes to warm a memory of, say, Ithaca, N.Y.’s Moosewood Restaurant or Disney theme parks; and volumes from TV chefs, including the best-selling “Recipes From My Home Kitchen,” by Christine Ha, who is blind and a James Beard Award semifinalist chef and restaurateur in Houston.

She seized renown in 2012 by winning Gordon Ramsay’s home-cook standoff, “MasterChef.” And Ha says that afterward she heard from others with visual impairments who felt represented and empowered by her presence in the competition. “I felt like I was able to show the sighted world: Hey, just because I have this disability doesn’t mean I can’t do this well.”

The most requested cookbook, tied with Meredith Laurence’s “Air Fry Genius,” is perhaps less familiar: “Cooking Without Looking: Food Preparation Methods and Techniques for Visually Handicapped Homemakers.” The book, by Esther Knudson Tipps, emerged from her 1956 master’s thesis for which she interviewed blind cooks in Texas. At the NLS, it’s enough of a mainstay that its available formats trace the arc of media from Braille to audio cassette, digital audio and e-Braille, and now print-on-demand.

Other popular titles include culinary cornerstones, such as the first volume of “Mastering the Art of French Cooking,” by Julia Child, Louisette Bertholle and Simone Beck (which itself is eight volumes in Braille), and “Joy of Cooking,” by Irma S. Rombauer, Marion Rombauer Becker and Ethan Becker - a wall-devouring 30 volumes in Braille.

“Oh, they have it!” Kristen Witucki, an NLS user in Highland Park, N.J., remembers thinking when she searched for that book, only then to realize its expanse: “Oh no …”

For Witucki, 42, who is a novelist, accessibility specialist and podcast host, owning a hard copy Braille book, until recently, was “a luxury.” She had sought “Joy of Cooking,” in part, simply to share in its ubiquity. “It’s so well-known,” she says. “Everyone who can see has that book.”

Ultimately, she passed on it. (Although 12 others have gotten it, according to the NLS.)

Christina A. Clift, in Millington, Tenn., requested an Instant Pot cookbook from the service in July. It’s one of the first hard copy Braille books she has owned, cookbook or otherwise, despite a love of reading. “I’ve never been able to really justify buying them,” says Clift, 48, president of the Memphis chapter of the National Federation of the Blind.

Clift, Witucki and others instead tend to find recipes online, though they’re careful to leave phones and Braille devices out of the kitchen to avoid an expensive mishap.

Clift cooks from a three-ring binder of recipes she transcribes into Braille, while Witucki will read an online recipe and memorize the steps. “I have a pretty good memory, but it’s not foolproof,” she says. “I would love to be able to have a book and just feel a little more laid back about cooking.”

Gomes, the author in California, has recipes that she copied into Braille from library books, or often will turn up the volume on her computer’s screen reader and use a wireless keyboard in the kitchen to navigate a recipe line by line.

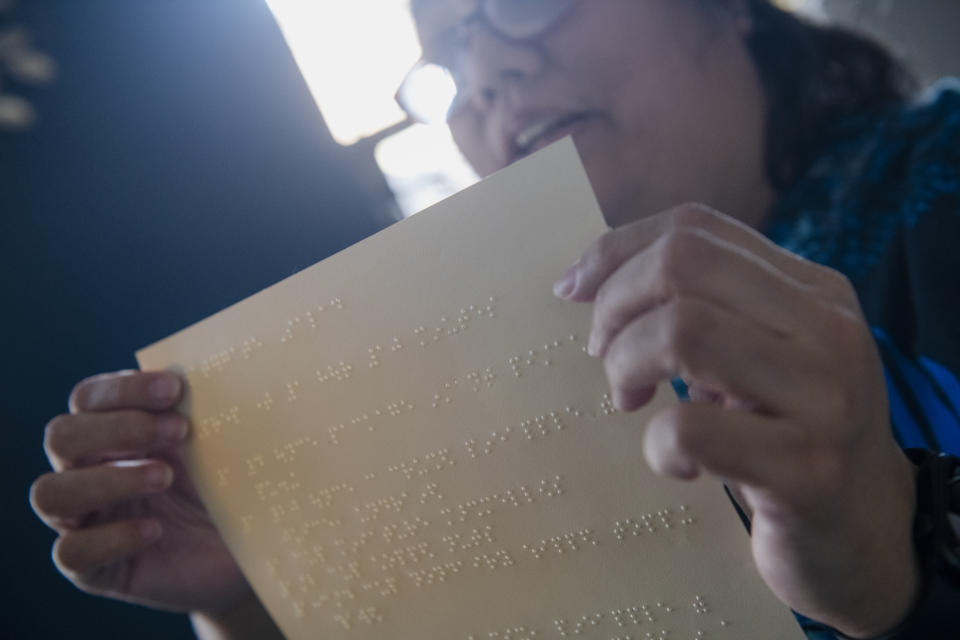

Although she takes full advantage of screen readers, audiobooks, e-Braille and other technology (Amazon’s Alexa helps Gomes skirt her air fryer’s unreadable touch screen, for instance), for Gomes each is part of a whole when it comes to reading, along with hard copy Braille. “I still like the feel of a Braille book in my hands and under my fingers,” she says.

In the kitchen it adds comfort to a space where she feels creative and generous; where she finds the memory of her grandmother in recipes for rum cake and apple pie, and of the spark that started her cooking at around age 9, about four years after she went blind from an autoimmune disease.

“I remember coming home from school one day and asking my mom if she would teach me how to make chocolate-chip cookies. And she said, ‘Okay, honey.’ But apparently the next day she called my pediatrician and said, ‘Sherry wants to make cookies! What should I do?’ [The doctor] said, ‘Well, teach her.’”

“What if she burns herself?” her mother asked.

“Do you ever burn yourself when you cook?’” the doctor replied.

“So one weekend she and I made chocolate chip cookies together,” Gomes says, “and I’ve loved cooking ever since.”

Related Content

How Trump reignited his base and took control of the Republican primary

What happened to Wall Street's post-George Floyd bet on Black banking?

Resignation at Harvard latest but not last salvo in GOP war on colleges