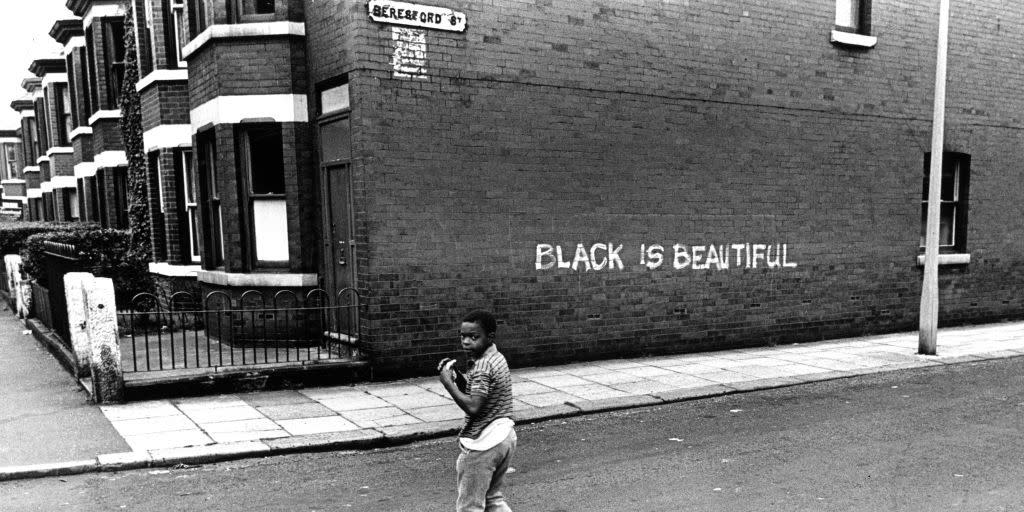

Black Is Beautiful but the World Is Often Not

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

At the close of the 1980s, a “Black is beautiful” Guinness beer ad circulated around Port-Harcourt, Nigeria. We saw the placards all over town and heard the slogan repeated on television and radio stations and from the mouths of those near to us. Even today, I remember the slogan, set atop 11 beer mugs, type-written in bold white letters against a solid black background: “Black is beautiful.”

The slogan might have been a commercialization of the “Black Is Beautiful” campaign of the ’60s, which sought to reverse the negative historical misconceptions surrounding the Black body and to undo the damage of white supremacy in the United States, but I would not make this connection at the time. Only decades later would I learn of the “Naturally ’62” campaign by Kwame Brathwaite, the New York City photojournalist who was born to Bajan immigrant parents, who documented members of the African diaspora in order to promote Black beauty. And even before Brathwaite’s campaign, there had been other versions of the “Black Is Beautiful” movement: for instance, the Negritude movement, in which activists like Aimé Césaire, Léopold Sédar Senghor, and other intellectuals of the African diaspora fought against white supremacy and Eurocentrism.

If the Guinness slogan was an attempt to sell more beer off of Brathwaite’s “Black Is Beautiful” campaign, it at least captured our attention in a positive light. We were small children then, all different shades of Black, and though we did not yet understand the power of such affirmations, we knew enough to know that the ad was telling us that we were beautiful, and we agreed with alacrity.

As I grew up, I would come to find out about the fraught history from which such a campaign was born. I would come to learn the history of my birth country, Nigeria, and I would come to see the ways in which Nigeria, after being colonized by the British, was in some ways left with an inferiority complex, believing strongly in the superiority of everything white. By the tender age of seven, I’d begun to see the preference that many Nigerians had for fairer skin, with a whole industry dedicated to skin bleaching. In supermarkets, one didn’t have to walk far to see pyramids of creams, a myriad of brands: Black & White Skin Tone Cream, Dermovate, Top-Gel, Ambi Fade cream, and more. It’s hard to tell what percentage of the country used bleaching creams back then, in the late ’80s, but according to a 2013 Al Jazeera article and a 2019 CNN publication, the World Health Organization (WHO) projected for both of those years that 77 percent of women in Nigeria continued using skin-lightening products, making Nigeria the world’s largest consumer of bleaching creams.

In any case, back in those childhood years, when my siblings and I were outside playing, adult men and women alike often asked if I was mixed and if my parents were white or Black. They referred to me as “omalicha,” “asa mpete,” “oyinbo,” “half caste,” and more. Some men went as far as asking if they could marry me, owing to my fairer skin complexion. The reaction was not the same toward my sister, who had darker brown skin.

By around age nine, my blemishes tormented me. Every mosquito bite and hot-oil splash left a mark that refused to fade. I wished for my sister’s skin because it was darker and showed no marks. To me, it was beautiful, and because of her I had come to equate dark skin with a resistance to scars. And yet the compliments I received for my skin told me I should prefer my own.

When I was 10, I emigrated from Nigeria to the United States, and after settling into life in Massachusetts and, shortly after, Pennsylvania and then later even more states—New Jersey, New York, Iowa, Georgia, Maryland—I saw the ways in which colorism was also at play across America.

In my fifth-grade class, during field day, my classmate said, “Be careful you don’t get any tanner.” I was not clear if the comment was in any way critical or if it was a reference to protecting my skin, but it was that day in America that I learned the word tan, this awareness of the different shades that skin could take by virtue of sunlight. I’d never known the word before, at least not the American skin-related context of it. It truly seemed to me back then as if, in Nigeria, the word did not exist. Like most things in life, if there was not a word for it, then it was not a part of one’s consciousness—not in any real way; it did not define or determine our movements, our tastes, our choices. This “tanning” had not been named, and so I had never known it as a thing even to pay attention to. I had never even known that my skin was capable of tanning. I simply ignored the warnings of tanning.

As an adult, I saw around me even more vestiges of colorism, how this obsession was global.

In Shanghai, on a trip I took to China with another fellow writer while completing my MFA, one very concerned local Chinese woman counseled me to use a parasol so that I wouldn’t get any darker. I was pretty, she said, but in order to maintain my beauty, I should use caution with the sun. I shook my head at her because I was offended by her advice. But then I noticed that she, too, was using a parasol. She was only giving me advice that she really believed would be beneficial to me—the same advice that she herself was taking. With that realization, I pitied her.

In 2012, I had just published my first book, Happiness, Like Water, and had been invited to be part of a literature panel in London. After the panel was over, several African women came up to me, asking me to be candid with them. “Just tell us,” they said. “What creams and soaps do you use? We want to get them too.” One of the women went on to speculate on whether I was using skin-lightening injections instead. I had not heard about these injections until then. I was astonished by their insistence on getting me to own up to something I did not in fact do. I felt saddened on their behalf, as I had for the Chinese woman in Shanghai, for not realizing the number that colonialism was doing on them.

In the years that followed, one friend whose skin was as dark or even darker than theirs vehemently disagreed with comments that praised both Alek Wek’s and Lupita Nyong’o’s beauty. Nyong’o had just won her Oscar for Twelve Years a Slave. My friend did not love his own dark skin, and therefore he did not love their dark skin. I argued that I found both women beautiful and that I found dark skin as attractive as light skin. My friend was also African and very educated. We talked about the ways concepts of beauty were socially constructed and about the ways colonialism might have affected our views and our own standards of beauty. Eventually, he contended that people were entitled to their own opinions, their own preferences. His was a matter of preference, he said. I couldn’t argue with that, and we left the conversation there. But in effect, these anti-Black comments came from Blacks and whites alike. From Blacks, they came primarily from Black men, who were quite open about their desire for light-skinned women.

Everyone is in fact entitled to opinions on beauty, but I was from a family of both light and dark people, and I found all of my family to be quite beautiful, light or dark. Even in my brief dating life, I gravitated equally toward all skin colors, from darkest to palest. I really did not have a preference.

But in mid-2016 and 2017, I realized how colorism had begun to affect me too when I started planning to conceive a child of my own. As the days and weeks and months of planning went by, I noticed myself agonizing over whether I should in fact bring a child into the world. Beyond that, I found myself agonizing over whether or not I should bring another Black child into a world that was already hostile to Blackness. By the summer months that followed, I had begun to take precaution with my skin, not for the purpose of preventing skin damage but simply to maintain what so many people clearly believed was a more beautiful complexion. I did my best to avoid going out on hot afternoons. I still believed in the beauty of all skin tones, and yet each time I had to venture out on a very sunny day, I consciously made sure to wear visors and hats.

And then, one day, shockingly, even to myself, I caught myself analyzing ways of making my future child’s life a bit more bearable where race relations where concerned.

That year, I recognized my view of the world in Maggie Smith’s poem “Good Bones”:

…The world is at least

fifty percent terrible, and that’s a conservative

estimate…

For every loved child, a child broken, bagged,

sunk in a lake. Life is short and the world

is at least half terrible…

I wanted to do all in my power to protect my child from what I knew was at least a half-terrible world, and so, for the first time in my life, I wondered if I should not have maneuvered a way of having a mixed child, so that the child would at least be protected by a lighter skin complexion in a world that clearly found lighter skin more favorable. In that moment, I understood the insidiousness of colorism and how even I was not immune to it.

For all my pride in my Africanness and Blackness, for all the times I got on my soapbox about why I loved both light and dark skin, I had fallen victim to colorism, if only in my thoughts.

Years later, when I would stumble upon another one of Maggie Smith’s poems, “What I Carried,” I would again recognize myself in her words:

I carried my fear of the world

to my children…

I carried my fear of the world

and apprenticed myself to the fear.

…

I carried my fear of the world

as if it could protect me from the world.

…

I never expressed my fears about how colorism might affect my child to anyone. I was so ashamed of having surrendered to the standards of a terrible world, if only for a short while. I spent months processing the experience. I had mornings when I began the day by consciously making peace with my knowledge of the world, reciting affirmations to myself about myself and my actual beliefs and my actual values outside of societal pressures.

After I had arisen from my moment of temporary insanity, and when my attempts at pregnancy did not work, I secretly blamed myself. Maybe the universe was punishing me because of those terrible self-hating thoughts. This was a period of genuine self-reflection in which I realized how even the staunchest, most self-confident individual is capable of succumbing to the pressures of the world. In some ways, I was no different from the Chinese woman, from the friend who denied Lupita Nyong’o’s beauty, from all the men and women in Nigeria who believed my light skin somehow superior. But luckily, I had climbed out of it—or rather, I am still climbing out. Being a person of color—or any other marginalized identity—is to constantly and actively affirm your own self-worth, your own beauty, your own goodness and desirability.

One day this past year, while on one of my long walks, while processing life as I often do during those walks, the Guinness beer commercial came to me, and I remembered myself as a child—the little girl I was even before I saw the commercials, before the questions and compliments began to come about the lightness of my complexion, about skin tanning. I remembered my siblings, how innocent we were then, before we learned the sociohistorical implications and ramifications of skin color. I realize now that those Guinness placards were a marker in time for me—a representation of that moment just before my eyes would become open to colorism. I longed to return to that time, before I became soiled by the weight of history—all of that history, and the pain and discomfort, and the self-doubt, and the struggle for renewed self-confidence, and all the muddy waters surrounding skin color.

You Might Also Like