The Birth and Life of Yosemite's El Capitan

It's one of Yosemite's most iconic features and, for mountaineers, one of the most celebrated climbs in the world.

El Capitan was born of fire. The 3,000-foot-tall granite cliff that rises up from the present-day Yosemite Valley in central California started forming roughly 220 million years ago, when ancestral North America collided with a neighboring tectonic plate under the Pacific Ocean. The slow, grinding impact forced the Pacific plate beneath what is now California, igniting a subterranean pressure cooker that liquefied the earth's deepest rock layers into red-hot magma.

The buoyant molten rock seeped upward through the earth's crust for miles, forming the bowels of an ancient chain of volcanoes not unlike the modern-day Andes. Some of the magma erupted, but most of it remained underground, where it slowly cooled over many eons, crystallizing into granite. One of the toughest natural materials known to man, granite is as strong as steel, and twice as hard as marble.

The subterranean granite reserve, or batholith, was 300 miles long and 70 miles wide. There El Capitan would have remained, had tectonic pressures some 10 million years ago not resulted in a fault system along the batholith's eastern edge. Uplift eventually ratcheted the batholith to the surface, where it would become the most recognizable part of California's Sierra Nevada mountain range.

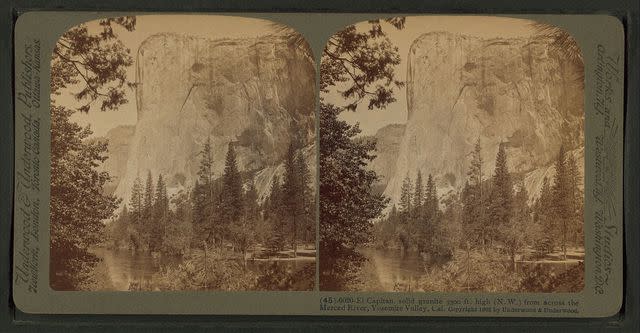

Over the course of tens of millions of years, the ancestral Merced River, draining from high in the Sierras, shaped the Yosemite Valley, chipping away the weaker rock between El Capitan and the earth's surface. Much as Renaissance sculptors freed human forms from lifeless marble, erosion painstakingly carved El Capitan from the Sierra Nevada.

Glaciers put the finishing touches on El Capitan during the most recent ice age, about 3 million years ago. The slow-moving masses of ice further scraped out the valley floor, establishing El Capitan's full 3,000-foot height while sloughing loose structures from the cliff's face, creating its famously stark, vertical wall.

When the glaciers retreated some 15,000 years ago and El Capitan was freed from the pressure of the ice, years of weathering with glacial meltwater refreezing and expanding shot narrow cracks through the cliff, which, as humans would eventually discover, were large enough to provide handholds and footholds.

The first humans to gaze upon El Capitan and the lesser granite formations of Yosemite Valley were likely the Ahwahneechee, a subgroup of the Miwok tribe, who lived in the western Sierras for thousands of years after the glaciers receded. They called the bountiful valley Ahwahnee, or "Place Like a Gaping Mouth." They hunted wild game, fished the Merced River, and harvested more than 100 types of edible plants.

Ahwahneechee names for El Capitan varied. In some reports, the cliff was called To-tock-ah-noo-lah, translated as "Rock Chief." Others knew it as To-to-kon oo-lah, or "Sandhill Crane," after the chief of the "Underworld People" of Miwok legend. Still others called it Tul-tok-a-nu-la, which originated from a myth about a measuring worm (tul-tok-a-na) that rescued two young boys stranded on the cliff.

Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo, the first European to explore California, sailed from Mexico in 1542. But it took three more centuries for white men to "discover" El Capitan. The Gold Rush of 1849 lured thousands of fortune-seekers into the Sierra Nevada and after the Miwok began repelling these interlopers, the new state of California hired bounty hunters and private militias to exterminate the region's indigenous people.

On March 21, 1851, a 200-man battalion purposed with "reclaiming" the land reached an overlook with views of Yosemite Valley. This was the first time a white man laid eyes on El Capitan. The battalion forced the Ahwahneechee to a reservation west of the mountains. Shortly after, Yosemite's original residents received special permission from the commission to return, but life in the valley was never the same, and their numbers soon dwindled.

In 1855, four years after the battalion's discovery, James Hutchings, an adventurous newspaper reporter, came across an account of their travels. Intrigued by the tales of 1,000-foot-high waterfalls and rock cliffs, he set out with two Indigenous guides on a five-day exploratory expedition. His resulting article about "Yo-Semity," published in a Mariposa newspaper, described a "singular and romantic valley" of "wild and sublime grandeur."

The next year, two ambitious miners opened a 45-mile horse trail leading into Yosemite Valley. The valley's first hotel, a rustic retreat with dirt floors and no panes in the windows, opened in 1857. Among El Capitan's earliest admirers were artists, like landscape painter Albert Bierstadt, who arrived in Yosemite in 1863. He wrote to a friend that he had found the Garden of Eden. Bierstadt's painting Looking Down on Yosemite Valley, featuring El Capitan, established him as one of America's top landscape artists.

Even by then, only a few hundred people had seen Yosemite Valley in person. But the area had captured enough of the public imagination that President Abraham Lincoln signed a bill to create the Yosemite Grant, a state-owned land trust to preserve Yosemite for future generations.

Near the end of the 19th century, conservationists, led by naturalist and author John Muir, began pushing for the area to become a national park. In 1903, Muir camped for several days with Theodore Roosevelt in Yosemite's backcountry, an experience that prompted the president to sign a bill three years later transferring the Yosemite Land Grant to the federal government.

In 1916, Yosemite National Park inspired a young man who would go on to become one of the most influential photographers of all time. Ansel Adams was just 14 when he and his family traveled from their home in San Francisco to visit the park. At the entrance, his father presented him with a life-changing gift: a Kodak Brownie box camera. Over the next six decades, Adams's black-and-white photographs of the American West, especially Yosemite, elevated photography to an art form. Among his greatest works is El Capitan, Winter, Sunrise, Yosemite National Park, California, a 13-by-10-inch portrait of a cloud-shrouded El Capitan, glistening white with snow.

After World War II, the availability of inexpensive army surplus climbing ropes and camping gear inspired mountaineers to begin exploring Yosemite's many towering buttresses, spires, and turrets. Throughout the 1940s and 50s, climbers worked their way up each of Yosemite's granite formations by pounding pitons, metal spikes with an eye-hole on one end to attach a rope, up the wall as they went. Yosemite Valley became the big-wall climbing capital of the world. But its biggest wall, El Capitan, was presumed impossible to scale for its height and verticality. When Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay summited Mount Everest in 1953, it was five years before anyone succeeded in climbing the granite monolith's sheer face.

In the summer of 1957, an audacious American named Warren Harding began the first attempt to climb El Capitan. He applied mountaineering techniques used in the Himalayas, fixing ropes between "camps" along El Capitan's monumental prow, which would come to be known as the Nose. The ascent required a small team of men 45 days of work, spread out over 18 months, to piece together a plausible route up, finally reaching the top in freezing weather on November 12, 1958.

Soon, others began refining Harding's techniques to scale the Nose more quickly and efficiently. Advances in gear and the creation of sticky rubber-soled shoes made the climb possible for more than just the world's most hardcore mountaineers. Today, "sending the Nose" requires a three- to five-day effort for experienced climbers, and less than a day for the world's elite.

Over the last half century, climbers have created dozens of additional routes up El Capitan on both sides of the Nose. Still, retracing Harding's original ascent remains one of the world's great outdoor challenges. One climber, Hans Florine, knows El Capitan more intimately than any other human ever has, and perhaps ever will. On September 12, 2015, the California resident made his record-setting 100th ascent of the Nose, bringing his total number of El Capitan ascents to 160. Yet with every climb, Florine, says he discovers something new. As much as we seek to learn El Capitan's true nature, it will always hold back something of itself, leaving us forever wanting more.

For more Travel & Leisure news, make sure to sign up for our newsletter!

Read the original article on Travel & Leisure.