Is there a link between excess body fat and inflammation? Yup. Here's why that matters

It's no secret that carrying excess body fat harms your health in many ways. This includes promoting insulin resistance leading to Type 2 diabetes. It also contributes to high blood pressure, high LDL ("bad" cholesterol), increased risk of heart disease and stroke, plus many other health problems.

But until recently, the reason for this connection has been vague. Increasingly, evidence suggests that body fat is not what we used to think it is. It’s not simply a storehouse of energy packed into fat cells (adipose cells) that sits there doing nothing until we call upon it to fuel our body. On the contrary, loaded fat cells are dynamic and can be potentially harmful. Here's what to know.

What is a fat cell?

Picture a fat cell as a cup made of connective tissue. Now take excess fat and pour it into the cup, filling it and expanding it to overflowing as occurs with obesity. The problem is the larger the fat cell becomes when loaded with fat, the greater the metabolic activity that promotes inflammation, a core factor contributing to many diseases.

For example, if excess body fat causes inflammation, it can disrupt the effects of insulin and contribute to insulin resistance. This means during digestion when glucose enters the bloodstream, insulin is supposed to "escort" it to the cells of the body. However, inflammation can make the cells resistant to the effects of insulin, causing glucose to linger in the blood creating a chronically elevated blood sugar.

As inflammation increases, insulin resistance gets worse and blood glucose concentration climbs, reaching the stage of prediabetes. Eventually, if insulin resistance becomes extreme and blood glucose concentration rises too high, the result is a diagnosis of Type 2 diabetes.

What is inflammation?

When it comes to serious chronic diseases that plague our society, inflammation is the hot new buzz word that is being used to explain a lot about what is going on. Unfortunately, inflammation is often poorly understood, especially since it is meant to be a good thing, but too often turns out to be harmful.

Here’s how inflammation is a good thing. When there is an injury or an invasion from something that should not be in the body, inflammation occurs. It’s a response from the immune system, the cavalry coming to the rescue. The initial response is from neutrophils, a type of white blood cell (think pus) that rushes in to fight infection. Next, big, mean macrophages gobble up invaders, and they also release compounds (cytokines) that trigger an alarm calling for reinforcements. The result is redness and swelling as the rush is on to destroy bacteria, viruses, dead cells, and debris. Afterward, inflammation stops, and healing begins.

Unfortunately, things don’t always go as planned and this same helpful process can backfire. When the immune response continues, even though it’s no longer needed, inflammation is unchecked and becomes chronic. Worse, the immune system can turn ugly and attack mushy cholesterol plaques in arteries. This can cause plaques to rupture with large chunks falling into the bloodstream, triggering a heart attack. In the brain, chronic inflammation is thought to destroy nerve cells causing memory loss and possibly contributing to Alzheimer’s disease. And inflammation may play a role in cancer, promoting the growth of cancer cells.

The impact of inflammation on heart disease has received considerable attention in recent years. Ironically, evidence suggests that inflammation can not only cause arterial plaques to rupture, but it can also contribute to creating plaques in the first place. The reason is inflammation can impact LDL (bad cholesterol) causing it to attach to the interior walls of arteries. As more and more LDL attaches, plaque grows in size, clogging the arteries.

The above scenario explains what seems to be a strange relationship between gum disease and heart disease. Chronic inflammation of the gums (gingivitis) is quite common, and it continually hypes immune system activity. This is like having a large group of soldiers poised and ready to kill whatever moves. Thus, flossing is an effective way to prevent inflamed gums that can generate an exaggerated immune response in the arteries.

It’s also recommended to take a daily dose of aspirin, not only for heart health but also to possibly protect against colon cancer and Alzheimer’s disease by reducing inflammation in the digestive tract and brain.

How can you reduce inflammation?

While flossing and aspirin are helpful suggestions, it’s important to address the core problem of excess body fat — the breeding ground for inflammation. When you do, be aware that fat is stored differently around the body, and some fat in excess is worse and more destructive.

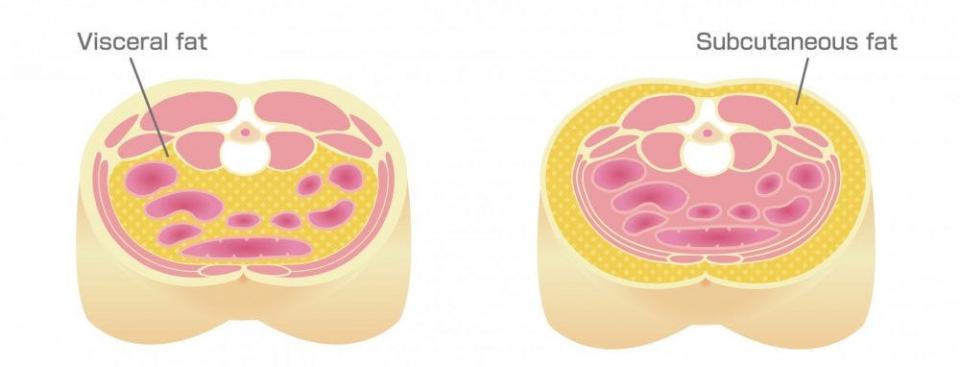

When fat is stored directly beneath the skin it is called subcutaneous fat, more prevalent in women than men. Subcutaneous fat, although it can be unsightly, is not as damaging to health as deep body fat around the mid-section that lies beneath the layer of muscle. This is called visceral fat, and it is public enemy number one. It is more common in men than women. However, after menopause, the hormonal profile of women becomes more male-like and more visceral fat is deposited. This helps explain why heart disease risk is lower in younger women compared with men of a similar age, but after menopause, female risk rises and eventually catches up to that of men.

If you want to increase the odds of living long and well, attack inflammation at the source. This means ridding the body of excess fat, especially around the midsection by following a healthy diet, exercising daily, and getting sufficient high-quality sleep.

Reach Bryant Stamford, a professor of kinesiology and integrative physiology at Hanover College, at stamford@hanover.edu.

This article originally appeared on Louisville Courier Journal: What is inflammation and how can you fight it?