The Bestselling Author and the Sea

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

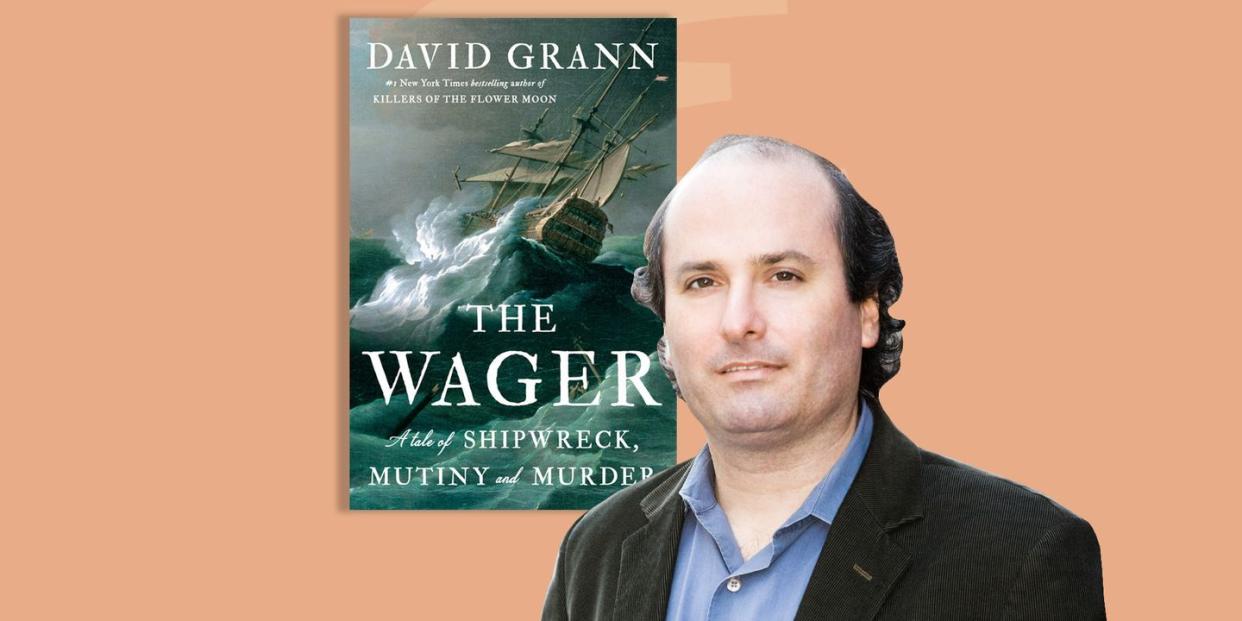

David Grann sat huddled on the floor of a little boat. He wore layers: a wool hat, long-johns and pants, turtleneck, sweater, a puffy jacket, wool socks and rubber boots, and gloves. A small wood stove tried to warm the boat, but the wind ripped through his layers, chilling his bones. He took every motion sickness drug he had on him to avoid throwing up. The captain and his two crew members kept the ocean at bay as best they could while trying to traverse the treacherous seas near Chiloé Island, off the coast of Chile. They navigated to an uninhabited island as the sea rollicked them for ten straight hours.

Grann needed a way to pass the time. Reading was out of the question. Standing was not an option. There was only the endlessness of looking out at the sea. Something, anything was needed to pass the hours. Luckily, Grann had an audiobook of Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick. He popped in his headphones and listened as he journeyed over similar seas that inspired Melville to write his magnum opus.

Grann was on his own mission to find answers to another story about men stranded in the Southern Pacific Ocean. He’d been researching what would become his newest nonfiction book, The Wager: A Tale of Shipwreck, Mutiny and Murder, and he wanted to see the land he had read about in 18th century sailing logs and stories published about men stranded on this island. “I hunkered down and I fucking just listened to Moby-Dick on this journey,” Grann told me over lunch in a Tribeca restaurant. “Talk about appreciating it, but not the most soothing thing to do, I’ll say in retrospect.”

$21.00

amazon.com

The island Grann ventured to, Wager Island, was named after the English boat that sank off its shores in 1742. The crew of the Wager was part of George Anson’s five boat fleet sent to attack Spanish vessels in the Pacific as part of the War of Jenkins’ Ear, with the goal of stealing their bounties and bringing them back to England.

The Wager was eventually commanded by the “burly Scotsman” Lieutenant David Cheap. Cheap started out as the first lieutenant for the Centurion, which was commanded by Anson. Initially, the Wager was captained by the 56-year-old Dandy Kidd, who was eventually transferred to the Pearl, a bigger and more accomplished ship, after its captain Richard Norris resigned from his post due to illness 37-days after leaving England. Captain George Murray, a nobleman, moved from the Trial, which was a sloop and “no man-of-war,” to command the Wager. Kidd was then promoted to lead the Trial. When Kidd died of a fever after the Pearl was separated from the rest of the fleet following its departure from Brazil for Cape Horn in January of 1741, Murray was moved to replace him. Cheap was promoted to guide the Wager and its depleting crew through some of the fiercest and most dangerous waters in the world—where typhoons, perfect storms, crashing seas, typhus, and scurvy all tried to destroy the vessel.

Eventually, the Wager found itself alone in the ocean, separated from the rest of the squadron. Then, it hit a rock and eventually began to crumble in the surf, only for the sick and dying men to find refuge on a nearby desolate island. There, the men fought for their lives, separated into factions, and built larger seafaring vessels out of a longboat and a cutter. Eventually a mutiny saw the first crew leave the island without its captain, heading for home. What happened next was a Rashomon-like tale of truth-telling and narrative building. After the few survivors made a long and arduous journey back to England, they told dueling stories about what transpired on Wager Island.

“These men believed their very lives depended on the stories they told,” Grann writes in the prologue to The Wager. Their versions would be spun to drum up support for their mutiny, leaving behind their captain and for the captain’s murder of one of their boatmates. Their lives depended on it, because for each man that arrived—on two separate vessels from two distant journeys, thanks to the mutiny—a court martial and a hanging awaited for those who were found at fault. “A naval court-martial was intended to more than adjudicate the innocence or guilt of those on trial,” Grann writes. “It was meant to uphold and reinforce discipline throughout the service.”

Grann captures all this in his new book, which is ostensibly about the ocean, but also about the nature of man and the narratives we tell. The Wager is similar to Grann’s previous books—The Lost City of Z: A Tale of Deadly Obsession in the Amazon and The White Darkness—because it focuses on man’s fight with the elements and himself. His stories are about man’s search for something greater while battling the very nature of being human.

“A voyage always reveals the soul,” Grann told me. “I think it's a lab. It's a perfect laboratory to test the human condition under extreme circumstances. And, inevitably, it begins to peel it back, peel it back, and reveal the hidden nature of each person, and the good and the bad.”

What makes The Wager stand out is that it’s a story about the sea—something people have been infatuated with for as long as we’ve been sharing stories. Stories of someone getting lost at sea date back to at least The Odyssey, Homer’s epic poem about a ship’s captain searching for home. The undercurrent of these stories runs a wide gamut throughout literary history, with poems and books like Daniel Defoe’s 1719 novel Robinson Crusoe, Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s 1791 poem “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner,” Jules Verne’s 1872 novel Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas, Nathaniel Hawthorne’s 1833 poem “The Ocean,” and Melville’s other novels, like Billy Budd, Sailor, Typee, Omoo, and White Jacket. The theme ultimately washes up on shore with more contemporary works, like Ernest Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea and James Cameron’s The Abyss. The first “blockbuster” was Jaws, a story of a man battling a monster in the ocean. Even the band The Decemberists has a song called “The Mariner’s Revenge.” What all this art has in common is a sense of adventure. These are tales of people going off to hunt a whale, or a shark, or a treasure, and instead discovering something more.

“The oldest, most widespread stories in the world are adventure stories about human heroes who venture into the myth-countries at risk of their lives, and bring back tales of the world beyond men,” the poet Paul Zweig writes in The Adventurer: The Fate of Adventure in the Western World. “These tales bind together the fragile island of human needs and relationships by affirming the possibility that mere men can survive the storms of the demonic world.”

For Grann, a voyage and an adventure make perfect stories because they contain multitudes. They offer the chance for a page-turner, but also a way to explore the nature of man. “Voyages have internal suspense because it's like life—you have no idea how that voyage went,” he said. “They begin with aspirations and hopes and dreams, and then they're suddenly filled with horror and calamity and disaster. So they make perfect metaphors for human existence and often mortality.”

Those very stories are read and referenced throughout The Wager, as the crew read what was available to them at the time. One crew member, a young John Byron, came from a noble family in England, but was seduced by the tales from the sea. Left with few prospects due to the fact that his older brother would inherit the family fortune as the eldest son, Byron joined the British Navy as a teenager.

“Byron was enraptured by the mystique of the sea,” Grann writes. “He was fascinated by books about sailors, like Sir Francis Drake, so much so that he brought them onboard the Wager—these stories of maritime exploits were stashed in his sea chest.”

Even Byron’s grandson, the legendary poet Lord Byron, was inspired by the tales of his grandfather, which were published in 1768 as The Narrative of the Honourable John Byron. (His story was also used by English novelist Patrick O'Brian for his 1959 novel, The Unknown Shore.)

“If you read Don Juan, you will find passages that are so obviously directly influenced from Byron's account,” Grann said. “He refers to it as ‘my granddad's narrative.’”

Men on the boat had read Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe and knew that it was based on a true tale. At the same time, Grann points out how ships kept log books that were turned over when a voyage ended, providing the empire with information for future voyages. Those logbooks were often turned into best-selling adventure stories. “Fueled by printing presses and growing literacy, and by a fascination with realms previously unknown to Europeans,” Grann writes, “there was an insatiable demand for the kind of yarns that seamen had long spun on the forecastle.”

Stories of past expeditions even came in handy for the mutineers as they tried to navigate a path from the unmarked island where they found themselves stranded. John Bulkeley, the Wager’s gunner, borrowed Sir John Narborough’s chronicle of exploring the Patagonia region of South America from Byron in the hope of using his story to create a map for their escape and eventual arrival in Brazil, on the other side of the continent. The key was always inside another story.

And while seamen—the real seamen, not the novices rounded up by the British government due to a lack of able-bodied volunteers to fill out the boat’s crew, many of whom could not swim—make a perfect audience for stories about hardships on the ocean, why have they transcended that space to become some of the most important stories ever recorded? Why does Moby-Dick still hold our imagination?

$15.99

amazon.com

Outside of the delirious writing and unforgettable characters, of course, Moby-Dick is a story about men stuck at sea with an unhinged and vindictive captain out for revenge against a whale. It’s an astounding novel that breaks and breaches nearly every rule any student has ever been taught about writing. It’s a fever-dream told on acid. At its core, it has one of the great antiheroes in Captain Ahab, and one of the most steady-handed narrators in Ishmael, who somehow makes a reader feel somehow safe in this unfamiliar world. It’s also an adventure, and an actual journey. But most importantly, it’s about man’s struggle to understand the world and himself. It’s about everything.

“Ahab, daemonic in drive,” the critic Harold Bloom writes, “is not too huge for his book because it contains the cosmos.”

But even Melville, a whaler and sailor himself, was inspired by a true story from the past. He was enraptured by the sinking of the Essex at the hands of a sperm whale in the Pacific Ocean, and how some of its men miraculously survived at sea and found their way home to Nantucket. Nathaniel Philbrick told that true story in his book In the Heart of the Sea, which was then adapted into a terrible Ron Howard film in 2015.

What all these stories have in common is their ability to bring the reader into a world that many of us, if not all of us, have not experienced. They’re a peek into the unknown—and who doesn’t love an invite to a place to which we haven’t been privy? They’re also tales that heighten the world we live in. Survival, especially survival in a largely unexplored place like the ocean, puts people under an immense amount of pressure and puts society under the same microscope. As Grann discovered in his research for The Wager, these large boats are floating societies.

“One of the reasons I focus so much on the building of these ships—in the building of these civilizations—is I wanted you to understand how this kind of floating civilization operates at sea,” Grann said. “How do they survive? How do they maintain order? How do they live? How do they have fun? How do they work?”

Ships have a system of order. There’s a chain of command. And in the days of The Wager, that command was largely dependent on the family you were born into. Many of the men on the boats were brought aboard against their will, bound to fulfill the duties of their empire-building monarchy. Those systems work until they don’t, leading to either chaos, like in the case of the Wager, or survival, also in the case of the Wager. It all proves to be ripe material.

“When they build this civilization, they float on that. And then what happens when it gets destroyed and they end up on an island?” Grann said.

What happened aboard the Wager was edited with each passing printing to become not only a series of best-sellers, but a corpus of influential stories that would be passed down from generation to generation. Byron, Bulkeley, a midshipman named Isaac Morris, and even some seamen “of dubious provence” published their stories. But even as each story entered the record, none took on more life than the overarching story that would come from George Anson himself via the Centurion's chaplain, Reverend Richard Walter. Anson supposedly provided the source material for Walter’s account, which became the best-seller A Voyage Round the World in the Years 1740-1744 by George Anson, which Darwin carried on his second expedition aboard the Beagle.

“He's the hidden hand behind this very self-pathologizing account that both burnishes him and the reputation of the empire,” Grann said. “And that book, I think, was the biggest selling piece of travel literature in the 18th century.”

Anson’s account lived on. His story is about his voyage on the Centurion, and how he eventually captured the bounty in the Pacific despite the ship being undermanned, then returned it to England. It’s a hero’s adventure. But as with any personal narrative, all of these stories needed to be pieced together to come to some truth. Grann spent years trying to unravel it, pulling together the story and deciphering the spin.

“Every book is a voyage where you hit rocks, you partly sink, hopefully you don't shipwreck and die. Hopefully it's not a total calamity,” Grann said. “It's a lot like a voyage. You set out with these grand ambitions and hopes and dreams, then, five years later, you kind of crawl to the finish. The ship is cracked and you're just like, did I make it?”

When my daughter was five years old, her aunt gave her a toniebox, which plays songs and stories from magnetized figurines. At first, she started with the preloaded Disney figurines, but eventually she got one with a series of classic stories, including an abridged version of Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island, the 1883 classic tale of adventure and treasure on the high seas. She’d place the figurine on the box and smack its side, which makes it skip to the next story or song, until she found Treasure Island. She was enraptured by the open ocean and the idea of a mutiny on the ship sent out to retrieve Captain Flint’s buried treasure.

Months later, while visiting a bookstore I told her she could pick out a book. Anything she wanted. She lingered in the children’s section, looking over what was available to her. She handed me books and asked me what they were. Eventually, she was drawn to a black book with a skull and crossbones on the cover: Treasure Island. She wanted that. She wanted me to read it to her, even though it was far longer than the story she’d heard and filled with words I needed to look up. She couldn’t help but be drawn to the tale of adventure, greed, treachery, and what it means to survive.

What my daughter didn’t know was that as a child, I found my own copy of Treasure Island. It was already in our house. A fraying hardcover book with a torn binding, it lived in our bookcase next to the Carl Sandberg anthology. When I moved into my own room, I had a bookcase attached to my dresser. In it, I moved over some of my father’s other books about baseball and his childhood collection of encyclopedias. I’d flip through the copy of Treasure Island, pretending it was a true story that I found. My own map. I finally read the beaten and worn copy in my room as I got older, and when I moved out, debated taking it with me. The book felt necessary, as if it were a roadmap for life.

My daughter and I never finished reading Treasure Island. She got bored of the old English style, as it took too long to explain each paragraph and page. The toniebox did a better job abridging. Eventually, she found her own adventure stories. But the book still sits on her bookshelf, waiting for the day when she finally remembers it and decides to begin her own journey.

You Might Also Like