How a Beloved Canadian Fishing Lodge Transformed Into a Luxury Wilderness Retreat

When Craig Murray initially motored his boat through Kenneth Pass and into Nimmo Bay, a remote inlet deep within British Columbia’s Great Bear Rainforest, it wasn’t love at first sight. The gray fog was so thick that summer afternoon in 1980 that he could barely see his boat’s bow, let alone the surrounding untamed swath of ancient cedars. But when he cut the engines, he heard the gentle rumble of what he was seeking—the waterfall local loggers had told him about. A quick wander on shore led to the source of the sound: a powerful cascade coming down from 8,711-foot Mount Stevens.

Jeremy Kopeks

More from Robb Report

Air France Unveils New Fully Flat Business-Class Seats With Sliding Doors

This 115-Foot Party Submarine Was Designed to Take Weddings, Concerts and Game Nights Underwater

At the time, he wasn’t thinking of its beauty so much as its potential to provide power and drinking water to a fishing lodge and family home. Murray, originally from Ontario, had moved west to Vancouver Island in 1973. After working in commercial fishing and logging, he craved a job that would let him lead a salt-of-the-earth life with his wife, Deborah, and their young children.

“I knew an isolated lodge in the wild would depend on a clean, quiet power source,” he says.

“Many a local told me I’d find a waterfall strong enough to turn a water turbine in Nimmo Bay. As soon as I saw the falls, I knew it was the place.” A moonshot thinker, he devised a scheme to tow a floating house by tugboat across Queen Charlotte Strait to the secluded bay, jury-rig it to a hydro system and start selling saltwater fishing trips.

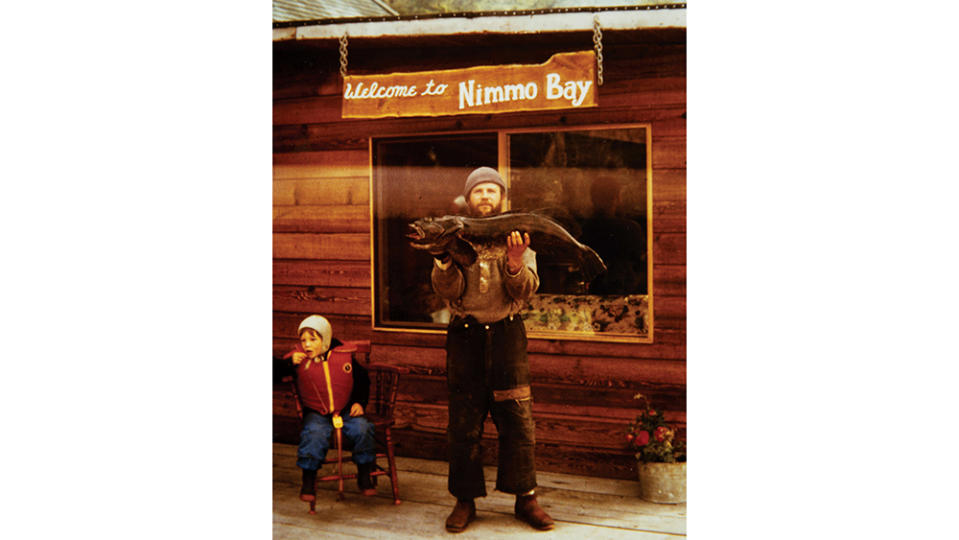

The lodge was anchored in 1981, and its first angling-obsessed guests arrived shortly after. Accessible by only air or sea, it was an adventure just to get there. The accommodations were low-frills. Deborah did the cooking, smoking salmon and foraging for dinner. Luckily, die-hard fishermen weren’t expecting turndown service or gourmet food. They came to hook monster-sized salmon day in and day out amid silent old-growth forests.

Courtesy of Murray Family Archives

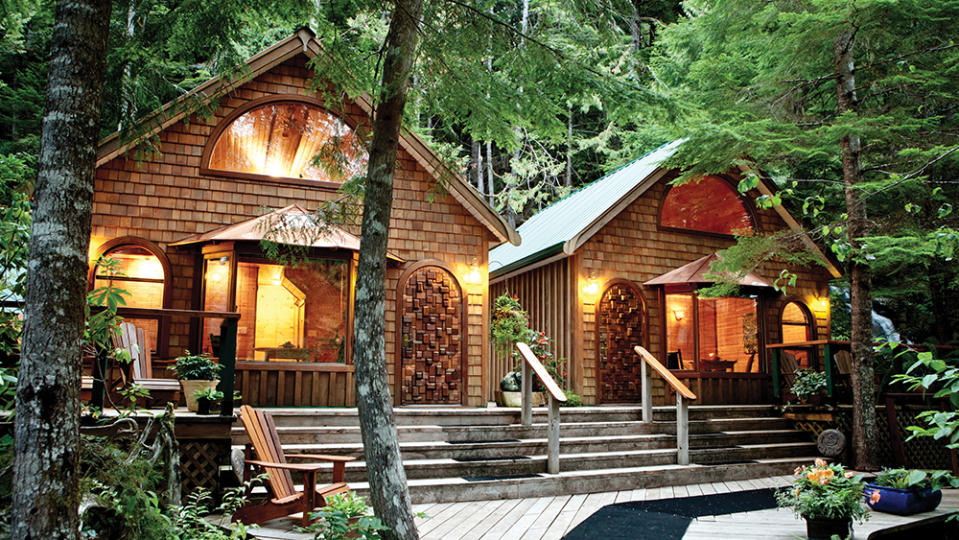

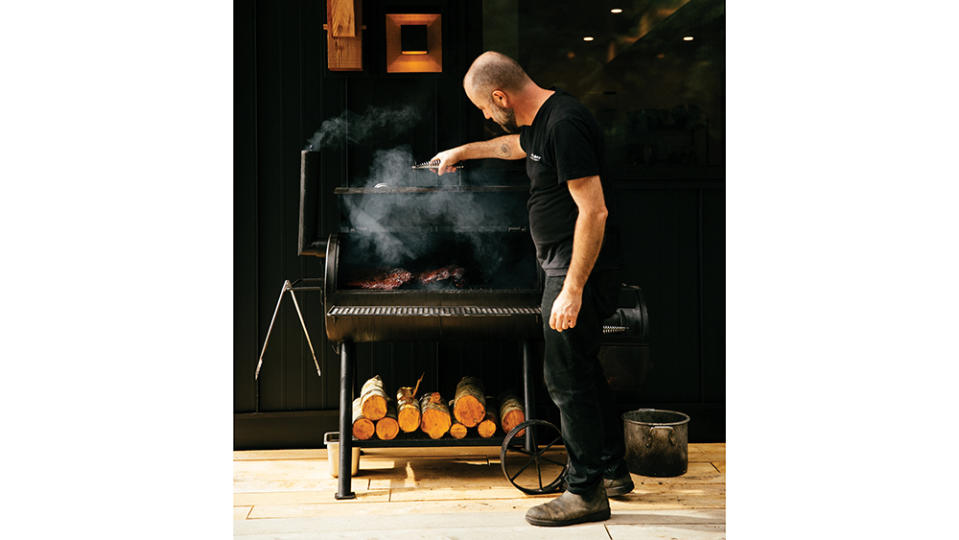

Those inaugural guests would barely recognize the family lodge today. It’s now a bona fide luxury resort run by the next generation of the Murray family, and the property’s brown-bag lunches have been replaced with meals prepared by Linnéa LeTourneau, a Canadian chef who cut her teeth at Michelin-star restaurants in Paris. The original team of six has grown to a staff of 70, including eight pilots, 12 guides and three spa therapists who conduct salt scrubs and Shiatsu massages on floating sauna docks or in glass-fronted tree houses. And while you can still go fishing, Nimmo Bay is attracting a new crowd with fresh adventures such as free-diving, heli-surfing and grizzly-bear viewing.

Jeremy Kopeks

Fraser, 44, the eldest of the three Murray children, is responsible for the lodge’s reinvention, which I’ve observed firsthand during four visits over the past seven years. He clearly inherited his dad’s ambition and imagination. And while he has made a great many changes to the business his parents started over 40 years ago, one thing that’s stayed the same is the importance of surprising and delighting the guests.

Craig built Nimmo Bay’s body of loyal patrons with a wild-eyed focus on enhancing the experience. In his fourth season, he teamed up with local helicopter pilot Peter Barratt to introduce the then-novel concept of catch-and-release heli-fishing, offering half- or full-day A-Star chopper rides to over 50 isolated rivers and streams, some of which had never been fished. Craig marketed it as “the most unbelievable sport fishing adventure of a lifetime,” and in short order the eight-person lodge went from hosting rough-and-tumble Canadian fishermen to welcoming Wall Street titans willing to spend thousands of dollars a day to hook a 20-pound Coho.

Courtesy of Murray Family Archives

Nimmo Bay earned a reputation as the ultimate guys’ getaway and quickly became the wilderness clubhouse for corporate boondoggles, attracting Virgin billionaire Richard Branson, former President George H. W. Bush and other big names. “It spoiled me for all fishing trips,” says Tim Jahnke. The 62-year-old chairman of the board of Elkay, a sink-and-water-solutions manufacturer, estimates he’s taken more than 200 clients to Nimmo over the past 20 years—and not just for the views. “It’s the only place I can let go and trust someone else to take care of my customers,” he says. “The team has a magical ability to intuit what someone wants and make sure they have it.”

Hal Schroeder, 69, isn’t even an avid fisherman, but after he first brought clients in 2001, he told the Murrays to book him for the same week for the rest of his life. “I’m an experience junkie,” says Schroeder, CEO of Concept Services, an Austin-based food-service equipment company. “The first time a helicopter landed me and my buddies on a glacier, and staff snuggled us in blankets and harvested glacial ice for our gin and tonics, I knew I’d always come back. A golf trip can’t form bonds like that.”

Schroeder, who is married, also loved the lodge’s old-boys-club feel. “It’s the place I go to be outdoors with my guy friends and just be a guy,” he says. “I used to tease [Craig’s wife] Deborah not to bring any girls around.”

When a boat dropped me at the dock for my first stay in the fall of 2015, Schroeder and his crew were sipping cocktails in Adirondack chairs around the fire pit beneath a sign with the word “Schroederville” painted on it. The men stared at me, a lone blond searching for a nature fix, in stunned disbelief, as if I were the region’s mythic spirit bear.

Jeremy Kopeks

Luckily, I’d made the journey from Port McNeill with Craig, who nodded to assure the group I was no threat to their man escape. And besides, women were slowly becoming a more common sight at Nimmo Bay. Five years earlier, Craig had handed the reins to Fraser and his wife, Becky. The couple had a different vision for Nimmo, one that included more guests like me, who were drawn to the wildlife and nature than to the fly-fishing.

Fraser didn’t know a life beyond Nimmo Bay. He, his brother, Clifton, and their younger sister, Georgia, were raised in life jackets and learned survival skills, such as how to dig clams for dinner and shoo away black bears, early on. Fraser was assisting guides on fishing expeditions by age 7, something he occasionally still does now. His siblings waited tables at the lodge restaurant while growing up but eventually went on to pursue musical careers—Clifton is a member of Canadian vocal group the Tenors, and Georgia a successful singer-songwriter.

After the 2008 financial crisis put the kibosh on corporate spending accounts, the resort struggled. At one point, bankruptcy seemed inevitable. Craig stubbornly believed a fishing lodge that operated a few months a year could still survive. But Fraser realized the only way to save Nimmo Bay was to adapt with the changing times. Instead of a fishing lodge, he envisioned a wilderness resort with a longer season, more stylish cabins, a tree house spa and unique experiences, from coastal wildlife safaris by boat to heli-mountain biking on ridgelines.

Jeremy Kopeks

Fraser started to share his ideas for expansion with the lodge’s longtime regulars. The successful entrepreneurs among them agreed a fresh direction was necessary. The new approach sparked enough support that in 2009, one guest anonymously gave the family access to $250,000 in investment capital to pay the bills, transform the activities and revive the lodge.

The generational transition was far from seamless. Despite the property’s off-the-grid location, Fraser and Becky believed it could compete with some of the world’s top lodges, including Alaska’s Ultima Thule and the Dunton Hot Springs in Colorado—and command comparable prices—if they offered a similarly refined suite of amenities. But Craig and Deborah were set in their ways. Fraser remembers his mother crying when she learned he’d replaced the restaurant’s garlicky, store-bought Boursin with a locally sourced artisanal goat cheese.

It took time and patience to attract an audience equally in awe of nature as of fish. Craig had worked with only a select few travel agents, but in 2011, Fraser and Becky attended Pure Life Experiences, a global luxury travel conference. Some agents’ eyes glazed over when the couple talked about the fishing lodge, but the mention of orcas and black bears commanded complete rapture. “Immediately, we shifted our marketing to focus on wildlife viewing,” recalls Becky. And the lodge’s new offerings found purchase with the regulars, too. When Fraser told Schroeder about their plans, he vowed to return year after year, but for a “mancation” rooted in fishing. That changed when he started going into the wilderness with guides. Schroeder still mainly fishes but acknowledges that “flying over mountains and glaciers, dodging grizzly bears and eagles that you could almost touch is hard to beat.”

The first evening of my 2015 stay fell on crab-boil night, a long-running and beloved Nimmo tradition. Guests—then still mostly fishermen—filed into the rustic dining room, gathered at communal tables and rolled up their sleeves as servers delivered trays heaped high with the region’s massive Dungeness crabs. Pints of beer overflowed. Tender crabmeat flew around the table. Craig still couldn’t help but play the garrulous host, hopping from table to table before grabbing a microphone and treating us all to a serenade of John Prine’s In Spite of Ourselves in his deep tenor. Eventually, the entire room broke into a sing-along of Johnny Cash’s Folsom Prison Blues. From the corner of my eye, I caught Fraser taking it all in and shaking his head as if admitting defeat.

Jeremy Kopeks

When the rowdiness died down, Fraser made his way to the front of the room to give the official welcome and a rundown of how things worked for the handful of new faces.

“We don’t believe in itineraries at Nimmo Bay,” he explained.“ Days are dictated by the unpredictability of weather and wildlife.”

Within minutes, a hand went up. “So, what’s the schedule for tomorrow?” a young man asked. Almost imperceptibly, Fraser shook his head once before quickly putting on a smile and reiterating that the team would share a weather report and game plan in the morning.

Diners pay thousands of dollars to relinquish control to Michelin-star chefs for bespoke tasting menus. Fraser aspires to gain the same trust from his guests. “People insist on itineraries, so we provide a loose agenda,” he says. “By day two, they usually give us back the reins.” The expectations of wildlife enthusiasts, it turns out, are far more demanding than those of fishermen. That first evening, a different guest lamented that his vacation would be ruined if he didn’t see a bear. Fall is bear season, and while the odds of spotting a grizzly or black bear are strong, a sighting is not guaranteed, just as hooking a whopper salmon on a fishing outing isn’t a sure thing.

Jeremy Kopeks

To avoid disappointment, Fraser has trained his team to help guests see beyond what they assumed would be their vacation highlight. “Nature happens when you take it all in as opposed to focusing on a whale or bear,” he says. “When guests slow down, they go home remembering the bird they saw taking flight in the morning fog.”

On my first trip, I assumed I’d be hunkered down behind a log with binoculars looking for a bear. But my guides, conservationist Adrien Mullen and Francisco Escobar, a former reserve officer with the Canadian military, led me on an epic adventure that involved off-roading in a van, crawling over a log to cross a river and stand-up paddleboarding alongside dolphins. By day’s end, we hadn’t seen a grizzly, but they seemed far more disappointed than I was. As we boarded our boat to return to the lodge, Escobar started to apologize yet again for the lack of bears. Right then a grizzly plodded into view. The moment was spectacular, but it was the thrill of the adventure, not the bear sighting, I would replay in my memory.

Jeremy Kopeks

When I returned one year later, in the fall of 2016, I was no longer in the minority. Couples and families outnumbered fishermen. This time I’d come for a wellness retreat rooted in mindful paddleboarding in the bay, free-diving workshops in remote alpine lakes, forest bathing amid the cedars and hot-cold therapies where I’d sweat in the floating sauna and then dive straight into the bay’s brisk waters. I stayed in one of the intertidal cabins, which had been renovated with L. L. Bean charm, constructed on pilings at the water’s edge. Twice a day, when the tide came in, I felt like I was in the Pacific Northwest’s answer to an overwater bungalow in the Maldives. The crab boil was now a seafood feast, served in individual bowls with salmon, clams and baby potatoes and paired with a sommelier’s selection of Canadian wines.

While the actual guest experience is dramatically different from the original fishing lodge Craig built, the familial hospitality remains the heart of Nimmo Bay. “I remember early on, a guide was fussing over my mom as she got in a kayak,” Fraser says, “and she scolded, ‘Give me the goddamn paddle. This place was better when it was worse.’ It was an important reminder that just because it’s shinier doesn’t mean it’s necessarily better.” The confused guide had only been doing what he’d been taught. Fraser now uses the incident as a training example. It helps his staff separate the guests who prefer low-maintenance service from those who want and appreciate more attention.

Case in point: Beth and Jim Hayhurst spent their 22nd wedding anniversary at Nimmo in October 2019. At cocktail hour, a staff member overheard the couple talking about wanting to renew their wedding vows one day. Their final evening, the entire staff surprised them with an intimate ceremony by the waterfall followed by a candlelit dinner. “They set up a beautiful ceremony for us,” Beth recalls. “I felt like I was surrounded by close friends or family.”

Fraser, much like his father, is always brain-storming how to improve the Nimmo experience. When the pandemic shut down tourism, he used the pause to tow in a new Scandi-minimalist lodge with floor-to-ceiling windows (the old one had started to sink) to the same location, sourcing power from the waterfall. He also invested in two new catamarans and opened a new restaurant, Little River, overseen by LeTourneau, who’d previously cooked at the Parisian gastronomic temples Verjus and Le Chateaubriand.

Jeremy Kopeks

On my most recent visit, in 2021, I free-dived for urchin and foraged for spruce tips and sea asparagus, all of which showed up on LeTourneau’s evening tasting menus. In place of the brown-bag lunches, guests are surprised with pop-up picnics on a mountaintop or a mossy forest floor. I kayaked out to the floating sauna one afternoon to find a bathrobe, slippers and basket stocked with a mizuna-and-mustard-greens salad, a thermos of winter-squash soup, pickled mussels from Salt Spring Island and a bottle of sparkling wine from Summerhill, an organic producer in British Columbia’s Okanagan Valley.

Nimmo 2.0 barely advertises fishing on its website. Fraser can rely on angling stalwarts, 15 percent of his clientele, to fill in salmon season, August through October. (Although even fishing fanatics like Jahnke, the sink titan, who now visits Nimmo with his wife, put down their rods for a day to go whale-watching or hiking.) Wildlife, wellness and culinary programming allow the lodge to remain open a full six months a year. With an 80 percent guest-return rate (and prices starting at $1,575 per person per night), Nimmo’s peak summer months are often reserved a year in advance.

Jeremy Kopeks

Schroeder marvels that his old boys club has evolved into what may be North America’s most in-demand summer camp. “You think you’re going for the fish, the eagles, the glaciers, the mountains, but that’s really just the stuff you see,” he says. “The magic of Nimmo has always been the people and how they take extraordinarily good care of you.”

Best of Robb Report

The Ultimate Miami Spa Guide: 15 Luxurious Places to Treat Yourself

The 7 Most Insanely Luxurious Spas in the World, From Tokyo to Iceland

17 Reasons the Caribbean Should Be at the Top of Your Travel Itinerary

Sign up for Robb Report's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.