Behind the Scenes of a Nude Photography Project in Quarantine

Until COVID-19 struck, the hallmark of Spencer Tunick's artwork was lots and lots of naked people packed together. He's perhaps known best for his shoot of 100 nude women gathered at sunrise in Cleveland in 2016 to make a statement outside of the Republican National Convention. They met in a secret location to evade any cops who might try to stop them—Tunick has been arrested a handful of times while creating his art.

This year, he planned to go to Mexico to direct participants in a butterfly refuge, in an effort to bring attention to conservation. But when the COVID-19 quarantines began, the plans were abruptly canceled. He spent weeks wandering around his home aimlessly, typing “vaccine” into Google over and over, unsure of what to do while he was unable to work. He lives in the town of Ramapo in New York’s Rockland County, where Governor Andrew Cuomo declared a containment zone due to the number of coronavirus cases. And he has a relative recovering from the virus. He considered organizing something local, with participants standing 12 feet apart but decided against it.

“Everything is so overwhelming to me right now that I just couldn’t even lift a finger to do anything. It’s so weird. I had this whole list of things I wanted to do. I was going to go through my negatives, I was going to learn Lightroom, which is a photo editing application,” Tunick says. “I was like, I’m going to do so much at home and then I just got so depressed that I couldn’t even do anything. The days just went so fast.”

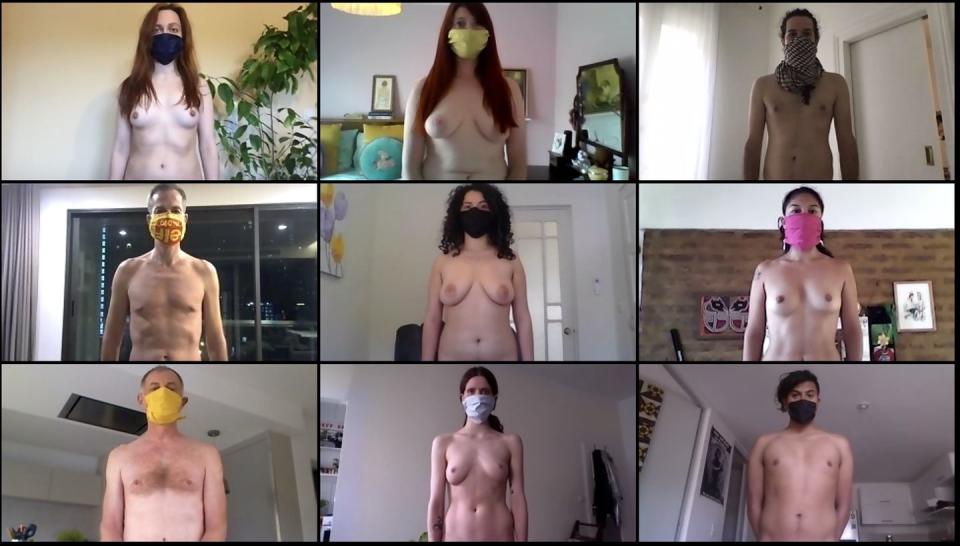

Then his collaborator and Studio 333 curator Alonso Gorozpe reached out about organizing a shoot via video conference. And they got to work looking for participants willing to pose nude while quarantined at home. For the project, which he's calling Stay Apart Together, they looked for people of all ages from the U.S., Mexico, Thailand, South Africa, India, Denmark, Lebanon, Argentina, Poland, Germany, Uruguay, Australia, Philippines, Canada, Netherlands, Israel, Ireland, Italy, Lebanon, Malaysia, Belgium, Colombia, France, and Italy. Tunick gave no direction about where the participants would be in their homes—most posed in living rooms and bedrooms. The quarantine locations, the contrasting backgrounds, become a part of the art. And he asked them to have masks to pose with— just not the n95 ones meant for medical professionals.

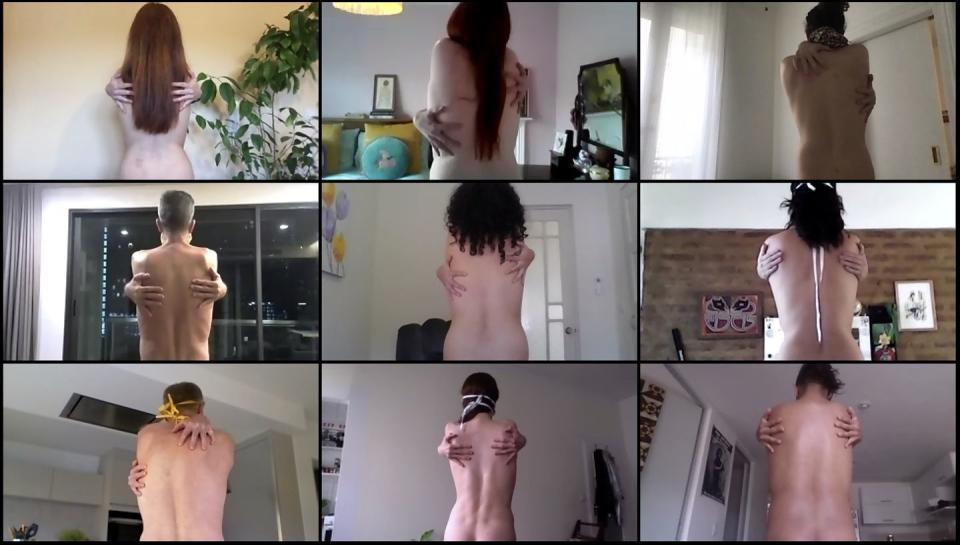

After the group joined the video conference, Tunick explained what they'd be doing. Then he counted to three, and everyone took off their clothes.

For about 20 minutes, Tunick directed the group, telling them how to pose, what to hold. But instead of his Fujifilm GFX100, a Medium format 100 Megapixel camera, he dragged his mouse to screenshot the images. It may not have been his usual camera, but it had that same satisfying click.

While the power in Tunick's art usually lies in seeing the human body in nature, which we so rarely see, the nudity in quarantine is meaningful in a different way. People remain separated, protected from the virus in their own homes. He sees a connection from strangers being nude together under these dire and unusual circumstances.

One model, Sara Gonzalez, is quarantined with her family, at her parents’ house in Mexico City. The 25-year-old had been living in New York, studying to become a chef, but went home after her campus and dorms closed. This weekend, her cousin called and asked if she wanted to be in one of Tunick’s installations. Once her cousin explained she wouldn’t need to leave the house, Gonzalez excitedly agreed. She locked the door, and opened her computer.

“[My family is] very conservative, so I felt like a teenager hiding to do something forbidden, even though I knew that I was—and am—proud of being in the project and doing nothing wrong,” she says. “It makes me think of all the music and art that are being created, of all the people that have started dancing and meditating again, of all the families that now have time to actually be together and makes me see that we have the ability to find art even in the hardest of situations.”

Over the last few days, Tunick has organized groups of 9 and 25 people, and he plans to continue with the shoots this week, for a total of 100 people. The final images will be available on his Instagram page and website. (The versions on Instagram are censored—Tunick has been fighting censorship on social media platforms for years. He wouldn’t specify the video conference platforms he used for this project because of censorship concerns.)

Tunick says the final project, with participants separated by the grid format of the video conferencing interface, reminds him of 1970s art from Annie Sprinkle, Yoko Ono, and John Waters. But in 2020, the contrast is in using those familiar quadrants, which have been our new primary mode of communication during this crisis, transformed into art. Tunick hopes the end results help start a movement.

“I hope people take off their clothes and make their own with their own friends. I hope this continues and doesn’t start and stop with me,” he says. “It’s really great to have platonic intimacy on video chat.”

Treat yourself to 85+ years of history-making journalism.

Subscribe to Esquire Magazine

You Might Also Like