At Atlanta’s Longest-Running Italian Restaurant, You Don’t Fix What Isn’t Broken

Welcome to Red Sauce America, our coast-to-coast celebration of old-school Italian-American restaurants.

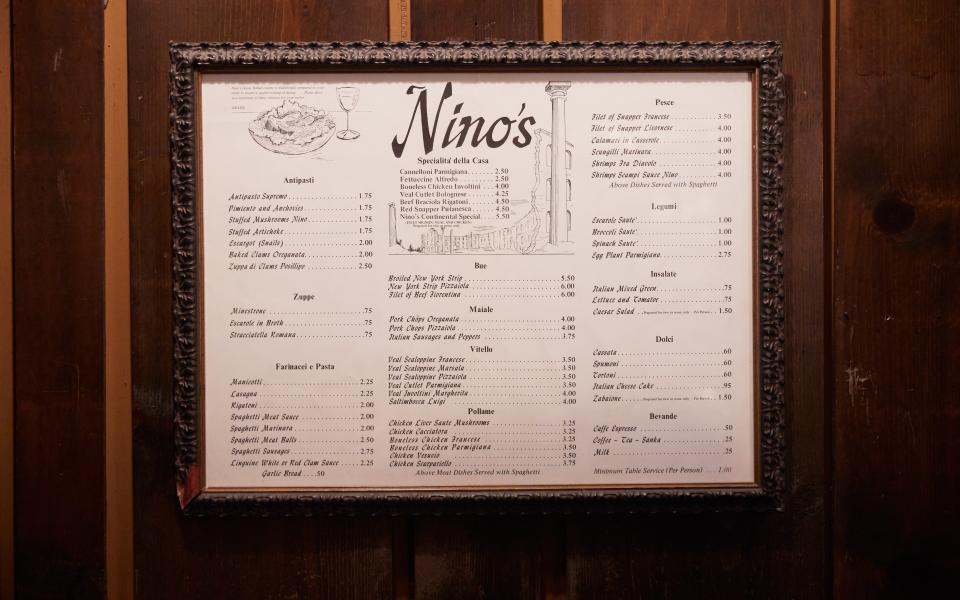

A black-and-white caricature of Nino Laporete hangs in a less-than-prominent position in the dining room at Nino’s Italian Restaurant. He was a jovial fellow from Genoa, who used to pop out of the kitchen belting Italian opera. A blown-up picture of his initial menu is still posted by the hostess stand, near a plaster statue of a vaguely Roman female figure. Baked clams oreganata, $2.00; minestrone, 75 cents; veal scaloppine Marsala, $3.50.

Die-hard customers swear that nothing ever changes at Atlanta’s longest-running Italian restaurant, a building of modest proportions that’s been open since 1968. It faces a street, Cheshire Bridge Road, long known for its sex clubs, adult video stores, and ancient restaurants such as the Colonnade (famous for its Southern fried chicken) and Nakato (a family-run Japanese restaurant that’s been here since the early ’70s). Cheshire Bridge remains patchy, but a slew of freshly built apartments hint at change for the street and its long-time restaurants.

Antonio Noviello, youthful and vigorous at 65, bought Nino’s in 1982, when the restaurant was in decline and the street at its lowest. Born on the Amalfi coast, he had worked in Monaco and Bermuda and landed in Atlanta, then a magnet for people who, like him, were ready to leave the cruise ship and resort industry. Both his recipes and his personality have consolidated the reputation of a beloved spot known for timeless Italian cuisine and old-fashioned hospitality. And almost 40 years later, the Noviella era is far from coming to an end. Instead, it has entered a new phase: a generational transition that promises to keep Nino’s in the family.

“I want to be retired,” Noviello tells me, with a sly glance at his middle daughter, 31-year-old Alessandra Noviello Hayes. As of last year, Hayes and her husband, Micah, have taken over daily operations of the restaurant in which she grew up. While her father uses the word untouchable several times during our conversation, describing the space he has ruled for almost four decades, his daughter is quick to point out the discreet changes: an old burgundy carpet replaced by tiled floors; the tables now covered with peach linens. She proudly brings out the 16-ounce wine glasses she now uses instead of the dated little-bitty ones.

Homeschooled from a young age, Hayes recalls how happy she was as a kid to leave the house and come to Nino’s at night for dinner. By the time she was 14, she was helping out as a hostess. By 18, she was the manager. And while she is proud of the restaurant’s long history—and of its chefs, including Alberto Nevarez, who immigrated to the U.S. from Mexico and has been in the kitchen for 35 years—she tells me she loves seeing customers her own age. “People are moving to Atlanta from all over,” she says, pointing out the newer patrons. They sit elbow to elbow with the old, pulling out their phones to take overhead shots of the food for Instagram.

Everything culinary still runs through Hayes’ father, whose position—either “consultant” or “executive chef” depending on who’s doing the talking—remains crucial to the restaurant. Noviello will never allow deviation from Alta Cucina plum tomatoes (grown in California but said to closely mimic the taste of those from Italy) that form the base for Nino's famous red sauce. “You have to look at the wall of the tomato,” Noviello erupts. “Some are so thin, you can practically see through them! They must be thick.”

Nino’s famous baked clams oreganata on the halfshell still figure on the menu (though it’s now $12 instead of $2), but dishes named after Noviello’s daughters have also appeared over the years. “I am a chicken,” Alessandra says, referring to the “petti di pollo alla Alessandra,” a dish of chicken breasts with eggplant and mozzarella that she particularly likes.

The restaurant makes its own ravioli and potato gnocchi from scratch and imports a lot of dry pasta from Italy. If Noviello had his way, people would eat appetizer portions of his pasta, then move on to entrées, such as the fresh veal butchered and pounded in the kitchen or the giant scampi with marinara sauce.

“I won’t touch what isn’t broken,” Noviello says.

And that’s how things go at Nino’s, where progress is so slight it’s nearly invisible to the faithfuls. Hayes, ever the dutiful daughter, smiles and nods: “We fine-tune. We don’t change.”

Christiane Lauterbach is the dining critic at Atlanta magazine and has been publishing her newsletter, Knife & Fork: The Insider’s Guide to Atlanta Restaurants, for 35 years.