How Artist Julie Curtiss is Making Waves with Her Quirky, Macabre Neo-Surrealism

A young girl, nude and blindfolded and wearing earplugs, sits in a V-shaped niche just below the shingled roof on the outside wall of a wooden house. She is looking away from us, lost in her own dark and silent world. It’s the first painting that Julie Curtiss has finished since returning from a residency in Japan. “I wanted a perfect little self-sufficient person,” says Curtiss, “but now it’s become more like pure isolation—a noncommunication.” It may be a selfie. Curtiss has insomnia and needs earplugs, an eye mask, and total darkness to sleep. Or is it a prophecy of our current era of social distancing? Like all Curtiss’s work, it’s passing strange.

It’s a late-winter day, and we’re in her Brooklyn studio, on the ground floor of a former factory. Curtiss, who grew up in a suburb of Paris, is half French and half Vietnamese. She’s a young-looking 37, with long black hair and a quiet, alert intelligence. The art is all around us in various stages of completion—paintings, gouaches on paper, and small sculptures of sushi that look highly edible until you notice that some of them are human eyes or lips and that they are actually made of plastic, clay, and paint. There’s also an upturned straw hat filled with spaghetti shaped into the form of a woman’s head. Another sculpture is made entirely of real ash-blonde hair. (Hair appears in most of the works here.) We’re in a disconcerting, dreamlike environment, with images that manage to be both familiar and surreal.

The art world discovered Curtiss only recently. After years of almost no recognition, she’s suddenly in demand. (She moved to New York in 2010 with her now husband, the artist Clinton King.) Curtiss recently joined the Anton Kern Gallery in New York, where she had a solo exhibition, Wildlife, last spring—one of the eye-catchers there showed an elegant woman in an evening gown, sitting on a toilet—and she’s just been picked up by the White Cube gallery in London. The attention ignited in 2017, after collectors bought everything she showed at Spring/Break, the curator-driven art fair for young talent. (Curators and artists acting as curators call the shots these days, not critics.) Her prices exploded, from $1,000 or $2,000 a painting to more than $400,000. Three of them sold last November at Phillips and Christie’s auction houses for a total of $1.1 million. Curtiss’s quirky, humorous, often macabre brand of neo-Surrealism had touched a nerve. She was able to quit her day job as a studio assistant for the artist known as KAWS—she had worked for him for four years. Before that, she’d toiled for a year in the Jeff Koons art factory, working on his “Hulk” series—or “Oolk,” as she pronounces it.

For Curtiss and for many of her artist friends, the initial springboard to recognition was Instagram. She’d started posting images of her work back in 2014. Loie Hollowell, an abstract painter of the same generation, saw the postings and got in touch. “Her detail and her precision, her sense of line and structure, and her really inventive and beautifully made work caught my eye,” Hollowell tells me. “I had to see it in person because Instagram lies.” Hollowell went to Curtiss’s studio and was blown away. They became and remain close friends. Hollowell, who was a little further along the road to recognition (she’s now represented by the Pace mega-gallery), helped Curtiss get into several group shows. Hein Koh, another artist who saw her paintings on Instagram, curated Curtiss’s revelatory solo booth at Spring/Break in 2017. “The Brooklyn and New York art community is amazing,” Curtiss says. “I’ve lived in Tokyo and I’ve lived in Paris, but the scene here, the community, is so tight, so supportive. It’s pretty special.”

Curtiss grew up in the suburb of Montreuil, east of Paris. Her mother, Therese Biver Curtiss, was French, a librarian in a school for social workers. Her much older Vietnamese father, Jacques Curtiss, was a technical photographer for an architectural firm. Jacques had been adopted by a Vietnamese woman who married a French soldier from Africa named Curtiss, and they brought him to Paris as a 12-year-old. The soldier soon disappeared. “My father called him ‘le père Curtiss,’ ” Julie says, “so I never knew his first name.” Her parents met in the 1970s through the Communist Party, which controlled Montreuil. “I grew up going to Communist Party meetings,” Curtiss says, but her parents also took her to museums, the Musée d’Orsay in particular, where she remembers being riveted by an anonymous Medusa-like marble head, grotesque and screaming. “I’m often galvanized by art that fascinates and petrifies you at the same time,” she explains. When she was six, her parents went to Vietnam, taking Julie along, so her father could try to find his biological mother. After five weeks of going to different villages, knocking on doors, they found her. It was a sobering experience that left Julie with a residue of uneasy memories. In France, the family had a reasonably comfortable, lower-middle-class life, but in Vietnam, Julie saw absolute poverty and people deformed by contact with Agent Orange. The Curtisses returned nearly every summer.

Raised as an only child, Curtiss spent a lot of time drawing. For years she wanted to be an illustrator, but just before enrolling in the École des Beaux-Arts she changed her mind. At the Beaux-Arts, she experimented with “creepy” sculptured heads made out of coconuts, with her hair and her baby teeth molded into them. “They were really intimate and dark, like shrunken heads,” or like the Japanese Noh masks that fascinated her. She entered some of them in the 2004 LVMH young artists’ prize competition and won. This gave her the money to finance an exchange semester at the Art Institute of Chicago. It was her first trip to America, and “it changed my life.”

Curtiss’s work is sometimes said to be influenced by the Chicago Imagists, artists who worked on the margins of Surrealism and popular culture, but she was barely aware of them at the time. Years later, when a friend showed her a catalog of drawings by Chicago artist Christina Ramberg, “I was in shock,” she told me, “because I felt such strong connections with her. I had to work my way through that language and evolve from there.”

The real life-changer was when she met Clinton King, a sculptor and performance artist who had just gotten his master’s degree from the Art Institute, in 2006. “I laid eyes on her at a karaoke bar in Chicago one night and said to my friends, ‘I’m going to marry that woman,’ ” King tells me. “It was a real case of love at first sight, which is dangerous.” They were two very different people who had a lot in common. Clint, as Curtiss calls him, had grown up “in a trailer in the middle of the woods” near Coshocton, Ohio. He’s six years older than she is, had been married and divorced, and is, as he puts it, a “natural extrovert, and she’s an introvert.” They were both committed to art, though, deeply into the anima thinking of Carl Jung, and fixated on Japan. King had been there when he was 19—his first wife was Japanese; Curtiss had been obsessed by manga as a teenager and was addicted to Japanese art, novels (Kawabata, Murakami, and others), and films. After going back to Paris to graduate from the Beaux-Arts, Curtiss joined King in Tokyo. It wasn’t easy going. “I was sharing a small apartment in a country where I didn’t know anybody, didn’t know the language, with a guy I hardly knew,” she says. After a year, they separated—King stayed in Japan, and Curtiss went back to Paris. Soon after, her mother was diagnosed with cancer, and Curtiss stayed with her for three years, during which she and King kept up a long-distance relationship. In 2010, Curtiss’s mother died, and Curtiss and King moved together to New York. They married at City Hall and then a year later had a small French wedding in Burgundy, where she’s recently taken over her parents’ “humble” country house.

“I’m often galvanized by art that fascinates and petrifies you at the same time”

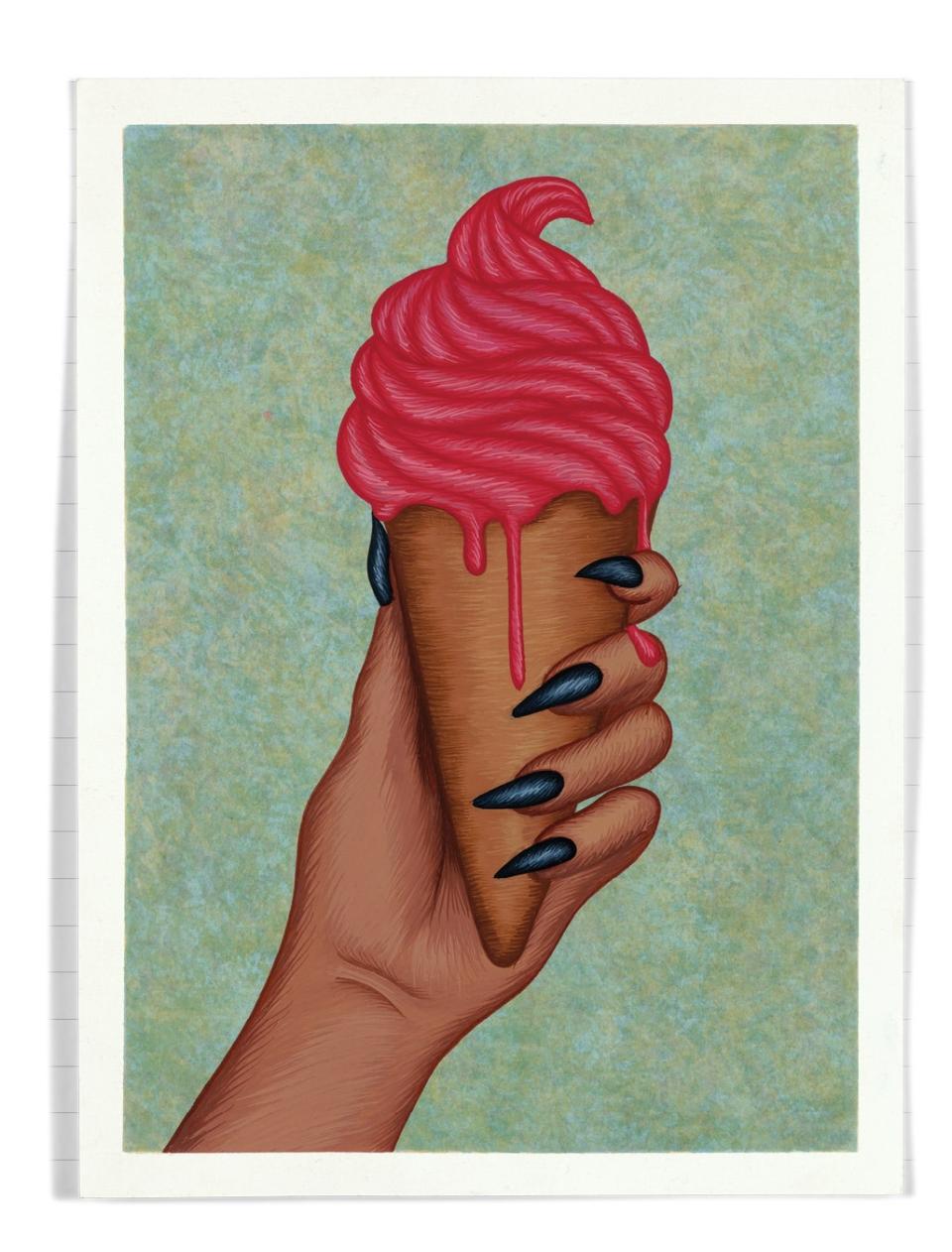

Curtiss brings us chilled cans of “pamplemousse” La Croix and starts laying out her new series of black-and-white gouaches on the studio floor. Offbeat color combinations have defined her work so far, and it’s a little jarring to see such a bold change. But the images have lost none of their ability to perplex and disturb. A giant python is ingesting a crocodile; a cockroach is about to drop into the part in a woman’s shiny black hair; two female hands with talon-like fingernails pinch the nipples of a pair of domelike breasts. No faces to be seen, of course, and the images have the same abrupt cropping that characterizes her previous work. “I’m not trying to spell it out,” she says. “It’s purposely ambiguous.” She uses illustration as an entry point to the subconscious. “When you illustrate, you’re already chewing the food, making it easily accessible. Not showing the face creates a distance, and there’s a mystery that comes from that.”

As a teenager, she was often very depressed. “I had a lot of therapy,” she tells me. “I think my art was very therapeutic—just doing it, making sense of things, creating out of a place of darkness.” Unlike King, who tends to work in bursts of activity followed by periods of intense social activity, Curtiss works for long hours every day. “I need art to extract this darkness and make sense of it and bring it to the light.” Darkness gets into her art in weird juxtapositions that make us laugh and also cause what Victor Hugo called a “new shudder.”

But Curtiss herself is anything but depressive. She recently started playing the piano again and has been practicing—Chopin, Satie, Schubert—on a keyboard in her studio. She’s also an “omnivorous” consumer of recorded music, everything from rock and jazz and vintage pop to classical and French chansons. She and King watch three or four movies a week at home, accompanied by their rescue cat, Dini, short for Houdini. (King is an accomplished magician.) I ask if she wants kids. “At least one,” she says—but not right away.

It can be tricky when one member of an artist couple suddenly outshines the other, but “Julie is married to a modern man,” as Hollowell told me, and King is all in with her success. His colorful abstract paintings were featured in the latest edition of Spring/Break in early March, in a booth of his own. “I made work until I was 34, and no one was paying attention,” Curtiss says. “I had no shows whatsoever. It was hard. I was working then, and I’m working now, and I’ll work when people stop paying attention, because eventually that happens. I’m just waiting for Clint to take it over, so I can chill.”

Originally Appeared on Vogue