Artist Carl Andre, known for minimalist sculptures and a murder trial, dies at 88

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published by The Art Newspaper, an editorial partner of CNN Style.

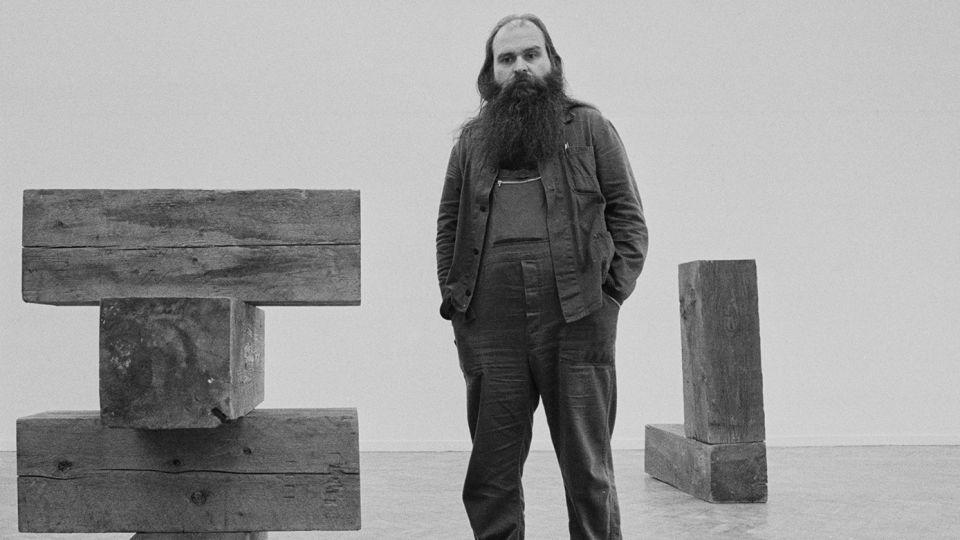

(CNN) — Carl Andre, the American sculptor who helped define the Minimalist movement and whose quiet, material-driven work forever changed the lexicon of contemporary sculpture, has died at the age of 88. His death passing was confirmed on Wednesday by the Paula Cooper Gallery, with which the artist had worked since 1964.

Since the mid-1980s, Andre’s legacy has been complicated by accusations that he killed his wife, the artist Ana Mendieta, who fell to her death from their 34th-floor apartment in New York City in 1985. Andre had insisted that Mendieta’s death was either an accident or a suicide, while others alleged it was the result of an alcohol-fueled quarrel between the two artists. In 1988, Andre was tried and acquitted on a charge of second-degree murder.

Subsequent exhibitions of his work have often been met by protestors who have criticized galleries and institutions for failing to acknowledge his involvement in the incident and holding signs that bear phrases such as “Where is Ana Mendieta?”

Andre was born in 1935 in Quincy, Massachusetts. His father, George Andre — who had emigrated with family to the United States from Sweden as a child — designed freshwater plumbing for ships. According to a 2011 profile of Andre in “The New Yorker,” naval plumbing of this sort was in high demand during World War II, and Andre’s father’s earnings grew such that his mother, Margaret Johnson, was able to quit her job as an office manager.

“My father always said, ‘I am old school and European, and my wife does not work,’” Andre told the magazine. “He had a hard time seeing other people’s points of view.” Andre’s father was also an amateur carpenter; the woodshop in the basement of the family home was a formative aspect of Andre’s childhood, as was his father’s love of poetry and propensity to read it aloud to his children. (Andre would become an accomplished poet in addition to his work as a visual artist.)

Andre attended Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts on a scholarship, after which he enrolled at Kenyon College but attended the university for only two months before flunking out. In 1954, during this period, he traveled to the UK to visit an aunt and later would cite a visit to Stonehenge on this trip as a turning point in his decision to pursue sculpture. He then served a year in the Army followed by a brief stint at Northeastern University — from which he also dropped out — before moving to New York City in 1957.

The following year, Andre met the artist Frank Stella through a mutual friend, and the two became close. On one occasion, Andre was trying to make a sculpture with some wood he had scavenged that was too big for his work space, and Stella — a burgeoning painter at the time — granted him permission to use his studio whenever he wasn’t in it. The arrangement continued, and in 1960 Andre began his “Element” series, in which pre-cut pieces of wood were arranged in rhythmic patterns and shapes, marking his step away from the impulse to manipulate material and towards the desire to reconfigure and recontextualize it.

“What I wanted was a sculpture free of human association, a sculpture which would allow matter to speak for itself,” he told “The Economist” in 2000. “Something almost Neolithic.”

In the late 1960s, Andre began a series of works referred to as “Plains and Squares” — thin metal plates placed together on the floor to create rectangular checkerboard patterns that viewers were typically invited to walk on. These visually simple works would be the series most widely associated with Andre’s oeuvre.

“I always assure people, there are no ideas hidden under those plates, those are just metal plates,” Andre said in a 2014 interview conducted by the Tate, dispelling the notion that these works were rooted in some kind of rigorous conceptualism. “They’re sitting there on the floor minding their own business. They’re not thinking; they’re free of ideas and it’s just an experience.”

In 1970, after just over a decade in New York, Andre received his first major museum survey, at the Guggenheim Museum. Reviewing the show for “The New York Times,” art critic Peter Schjeldahl wrote: “Andre is not much fun. Puritanically severe, his work rewards sensitive perusal with some nice surface effects and a certain feeling of unease.”

Schjeldahl added that the work “presents itself to the viewer with an aggressive air of completeness and finality, as if each were the only, or anyway the last, work of art in the world.”

In 1985, Andre was arrested and charged with murder in the death of his third wife, Mendieta, whom he had married eight months earlier and who fell her death from a window in the couple’s apartment — where Andre continued to live for the rest of his life — in Greenwich Village.

On the night she died, Andre said in a 911 call that “she went to the bedroom and I went after her, and she went out the window,” though he later changed his account of events somewhat, successively stating that Mendieta had gone to bed alone and that, upon entering the bedroom, the window was open and he noticed her missing.

In 1988, Andre was acquitted, but the controversy around Mendieta’s death slowed the rise of his career, and for decades he remained elusive, spending substantial amounts of time abroad and exhibiting with less frequency. (Just last year, curator Helen Molesworth released a true crime podcast of sorts — “Death of an Artist” — that set out to reexamine the case.)

“It didn’t change my view of the world or of my work, but it changed me, as all tragedy does,” Andre said when asked about her death in a 2011 interview with “The New York Times,” a rare example of his being willing to publicly discuss the matter.

And for the rest of his career — which included countless gallery and museum exhibitions as well as a major 2014 retrospective that began at Dia Beacon before traveling to Los Angeles’s Museum of Contemporary Art — his shows were often targeted by protestors who held Andre responsible for Mendieta’s death.

“Carl Andre redefined the parameters of sculpture and poetry through his use of unaltered industrial materials and innovative approach to language,” read a statement released by Paula Cooper Gallery announcing the artist’s death. “He created over two thousand sculptures and an equal number of poems throughout his almost 70-year career, guided by a commitment to pure matter in lucid geometric arrangements.”

“I think art is expressive but it is expressive of that which can be expressed in no other way,” Andre said in a 1970 interview with “Artforum.” “I find that my greatest difficulty and the really most painful and difficult part of my work is draining and ridding my mind of that burden of meanings which I’ve absorbed through the culture — things that seem to have something to do with art but don’t have anything to do with art at all.”

He is survived by his fourth wife, the artist Melissa Kretschmer, and a sister.

Read more stories from The Art Newspaper here.

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com