A New Art Center With a Tower Designed by Frank Gehry? It's Time to Head to Arles!

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The city of Arles, in southern France, is a quintessential Provençal place. Immortalized by Vincent van Gogh, it has long been a center for trade, commerce, and—even in ancient times—the arts. Its specialty has never been innovation, but that is about to change.

Earlier this year, the Luma foundation unveiled its completed 27-acre arts complex, the legacy of its founder, collector and Arles native Maja Hoffmann. She spent more than a decade working with a who’s who of architecture and design eminences to transform an abandoned manufacturing area into a center of creative industry. It will house part of her extensive art collection, but it is no mere museum. Instead it offers a total environment at the intersection of art and ecology.

Luma Arles is several things: performance space, archive, and park. Most of all, it is an homage to the unique ecosystem of the Camargue region, where the Rhône river meets the sea and where birds from northern Europe stop en route to Africa during their annual migration. Depending on the time of day, there is also a steady stream of light as rich as olive oil but as light as rosé, a light that has inspired generations of painters, of whom van Gogh is merely the most famous. “The light is there every day, and it’s a miracle,” Hoffmann said before the opening. “There’s a historic patrimony and a natural patrimony, and the two intersect in Arles and the surrounding region.”

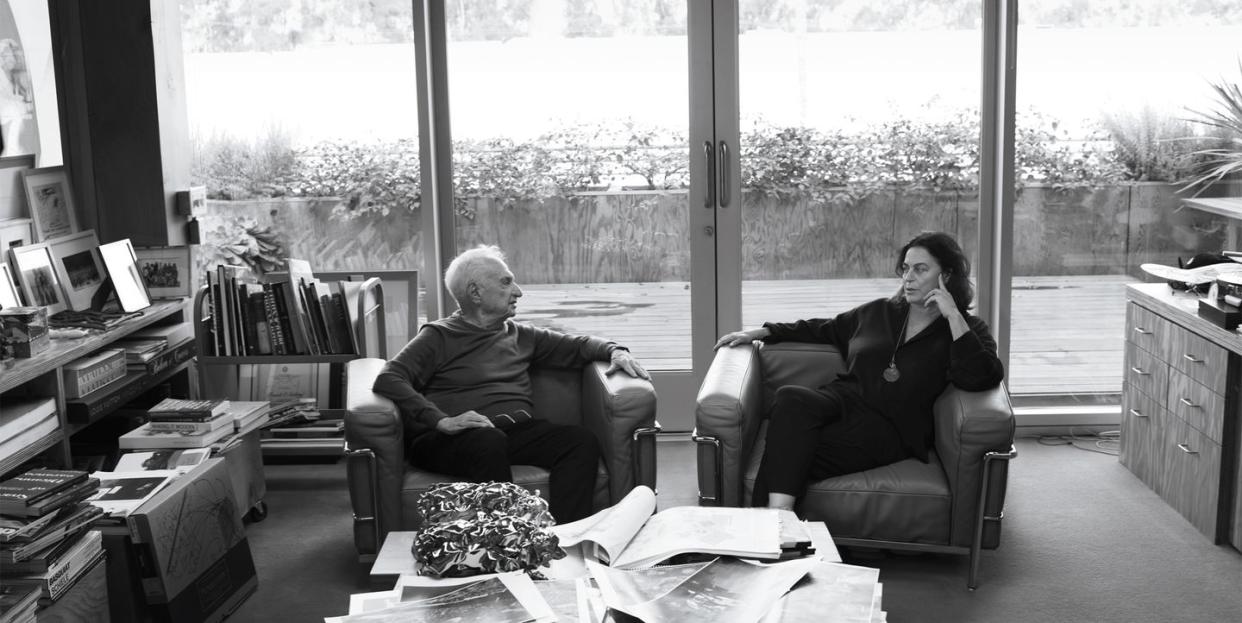

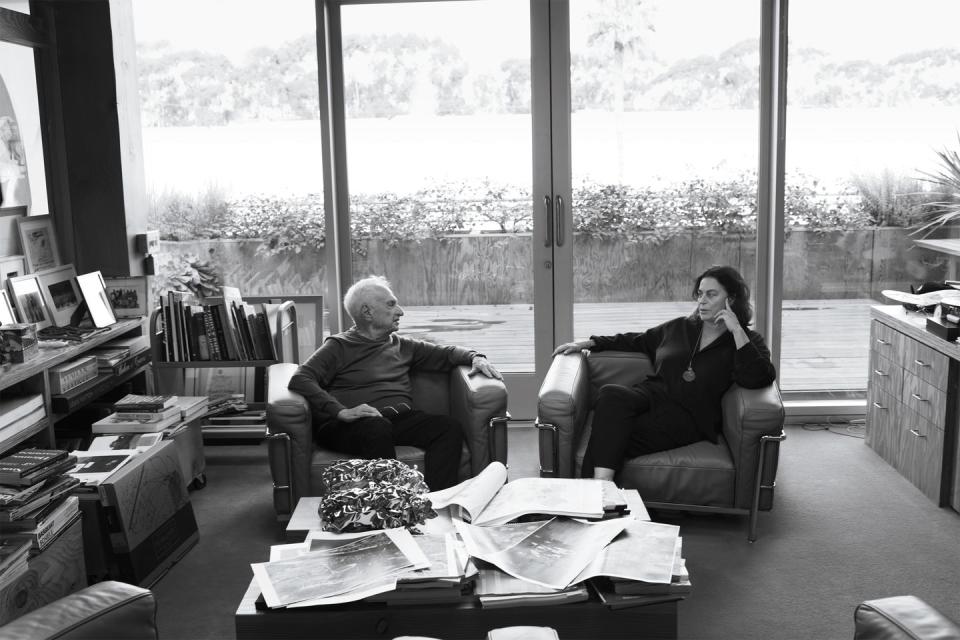

Luma’s centerpiece is a tower designed by Frank Gehry. Striations on its metal exterior reflect the sun in different colors; from afar it looks a bit like a stack of Jenga blocks about to collapse. But the building is not meant to be contemplated as a solitary creation. Inherent in the design is its relationship to the rest of the campus, which includes several buildings renovated by the noted architect Annabelle Selldorf, and to the nearby Roman ruins for which Arles is also famous. “The round form of the tower is inspired by the Roman amphitheater, with which I wanted to create a link,” Gehry said. “Its conception is linked to natural forces—how the wind integrates with the rotunda, how to capture the movement of air in an interior space.”

Hoffmann’s contemporary collection on display inside that tumbling tower is not so vast as to be exhausting; a few carefully chosen pieces, typically with pointed messages, are meant to speak to visitors. One of the more visceral is the Thai artist Rirkrit Tiravanija’s collages of newspapers titled “The Days of This Society Is Numbered.” These are fairly simple works: Newspapers are plastered onto large linen canvases and covered with acrylic letters. Most of the papers used in the series are from 2008, and they detail a society on the verge of the subprime mortgage crisis. From the perspective of 2021, looking back at all the ravages that crisis caused, the seismic shifts in global politics it triggered, is a sobering experience. To look at headlines like “Lehman’s creditors scramble for position” (from the International Herald Tribune on September 16, 2008) is to look at a horror story in slow motion, a tale whose ending we already know.

But perhaps the most impressive aspect of the Luma project is the way it has transformed its site—an abandoned 19th-century rail yard—into a sustainable patch of green that is now the largest public park in Arles. More than a century ago the location was where France’s Société Nationale des Chemins de Fer manufactured train cars for use in the Midi region and beyond. Today the same place, which had been 10 acres of concrete abandoned for more than 30 years under the punishing heat of the Mediterranean sun, is a bona fide microclimate, complete with a bucolic pond and more than 1,100 trees and shrubs.

The project is the brainchild of the Belgian landscape architect Bas Smets, hired by Hoffmann at the age of 32 without all that much of a résumé. He said he recalled walking with Hoffmann through the site during an early visit to Arles and listening to her explain her vision for the park she wanted to create. “I remember saying, ‘Here? Really?’ And Maja said, ‘Yes.’ ”

His assignment was clear enough, albeit daunting. “What I proposed was to model how nature would come back to this barren place over the next 200 years, and then accelerate the process. There was absolutely no vegetation, no soil, and no water.” Two years later, after having 120 workers on-site nearly every day, he managed to bring green back to a place that had not seen it since before the Dreyfus Affair. How did he do it? Smets decided to pump water from a nearby canal into a central pond, around which he built a series of mounds planted with endemic vegetation. Trees provided shade and helped reduce the ambient temperature at the site. “The volume of the pond evaporates every 10 days,” he said. “This is what makes it a microclimate.” And a former industrial site is now a living, breathing organism.

This story appears in the October 2021 issue of Town & Country.

You Might Also Like