Around the World in Hot Sauce: An Illustrated Tour of 18 Varieties

Hot sauce is a $1.3 billion industry in the U.S. alone. Around the world? Priceless. Take our international tour.

Serious Eats / Vicky Wasik

If there's one constant in global cuisine, it's that people all over the world like spicy food. And food cultures across the world have come up with countless ways to dry, crush, smoke, pickle, brine, and confit chiles into condiments, developing hot sauces that give dishes extra dimension and heat. In the US alone, hot sauce is a $1.3 billion industry.

Below is our illustrated tour of this global hot sauce heritage, but first things first: what exactly is hot sauce?

Defining Hot Sauce

For our purposes, a hot sauce is any spicy condiment, the bulk of which is usually chiles, rendered into a liquid through water, vinegar, or fat. One key word here is "condiment," which excludes spicy cooking sauces or broths spiked with chiles. But for our purposes, we're considering chile pastes to be hot sauces, as splitting the difference between the two can be tricky business (and pretty academic).

There are countless species of chiles, but just a few, all members the Capsicum genus, account for most hot sauces. Bell peppers, cayenne, and jalapeño are all variants of C. annuum; hotter habanero and Scotch bonnet peppers belong to C. chinense; and C. frutescens includes tabasco and peri peri.

A pepper's heat is generally measured using Scoville units (SHU), a scale originally based on diluting peppers with sugar water and noting how much or little dilution is needed to make the heat just-noticeable to the human palate. For reference, Tabasco sauce (about 95% water) clocks in at about 2,500 to 5,000 SHU, while a tabasco pepper measures about 30,000 to 50,000 SHU. Police-grade pepper spray ranges from 500,000 to 5 million SHU, and pure capsaicin, the chemical that provides heat in all peppers, is about 16 million SHU.

Other ingredients—salt, vinegar, sugar, garlic, and countless others—of course affects the flavor and texture. And processing methods vary considerably. Some hot sauces are totally raw. Others are cooked, some are infusions, and still others are fermented.

Eaters around the world have spent thousands of years figuring out new ways to make their food hotter, so compiling anything close to a definitive list of hot sauces would be impossible. However, plenty of the more unusual hot sauces in the world are similar to, or influenced by the styles listed below.

With that out of the way, here's our region-by-region tour of hot sauces around the world.

Asia

Achar

Serious Eats / Max Falkowitz

Chopped Indian pickles—made from fruits, vegetables, and spices cooked in oil or brined—are the most common condiment for adding heat to samosas, curries, and countless other South Asian dishes. Mango, lime, tomato, onion, cauliflower, cucumber, and fresh chiles are all common ingredients. Achars are closely related to pickled chutneys, and both vary widely in flavor, texture, composition, and heat across the subcontinent, but their hallmark is an oily, puckering heat.

Chile Oil

Serious Eats / Vicky Wasik

Made from vegetable oil infused with chile peppers, chile oil is a staple of several East Asian cuisines, but especially Sichuan. It's typically made by adding dried red chiles (such as tsin tsin peppers, and some Sichuan peppercorns and other spices if you're feeling fancy) to hot oil, then letting the mixture cool and sit for a few hours, allowing the chile's flavors to infuse the oil. The finished product is served tableside as a condiment, as part of a communal hot pot meal, or gets stirred into noodle dishes, stir fries, and salads. Some chile oils strain out the chile pies while others go all-in for a chunky, oily paste.

Japanese chile oil, or rayu, is similar to its Chinese counterpart, and is also used in soups and stir fries; Taberu rayu, a brand of milder oil with a crunchy mix of fried garlic, chiles, and sesame seeds from Okinawa, has been a wildly popular addition to noodle and rice dishes across Japan since 2009.

The Italian olio di peperoncino originates from Calabria (the toe of the boot known for its fiery peppers) and uses olive oil as a base. It's made in a similar fashion as Asian chile oils, and is usually served with pasta as part of the simple "spaghetti, aglio, olio e peperoncino" dish.

Gochujang

Serious Eats / Max Falkowitz

One of Korea's most popular condiments, second only to kimchi, gochujang is made from chile peppers, sticky rice, fermented soybeans, a sweetener and salt. It has a thick consistency similar to tomato paste, and it strikes a balance of spicy, sweet, and funky flavors thanks to the fermentation process it undergoes.

You'll find it in served with bibimbap and blended into spicy ssamjang, a condiment common for Korean barbecue where it's dabbed on meat and wrapped in lettuce. It's also a key ingredient in many stews, and you'll find chefs adding it to non-Korean dishes for its distinctive funky heat. Traditionally, gochujang was made in the home and fermented in earthen pots, but with the advent of commercially-produced gochujang in the 1970s, the homemade stuff became far less common.

Nam Phrik

Serious Eats / J. Kenji Lopez-Alt

"Chile water," or nam phrik, is a staple Thai condiment, somewhere between the consistency of a jam and a salsa, that you'll find served with just about every meal in northern Thailand. Also like salsa, nam phriks vary wildly in heat level and ingredients. Most nam phrik recipes include crushed chiles, shallots, garlic, and lime, and often incorporate a fermented savory element such as shrimp paste or fish sauce. Some versions go far beyond the standard template, like nam phrik ong, with pork and tomatoes. Nam phriks are served with everything from seafood to sausage, or treated as a dip, scooped up with cucumber slices or pork rinds. Here's how to make your own.

Sambal

Serious Eats / Ben Jay

Traditional Indonesian sambals are made from chile peppers coarsely ground into a paste with additional ingredients that might include vinegar, ginger, sugar, shallots, and lime. Sambal oelek, one of the most popular varieties, is traditionally made with raw ground red chile, vinegar, and salt, and often serves as a base for more complex sambals. It delivers a sharp heat alongside a certain sour tang, and tends be somewhat chunky.

Malaysian sambals are similar, but they're distinguished by some eclectic ingredients. Sambal belacan uses fermented shrimp paste to add a distinct saltiness, while sambal tempoyak uses stinky, sour fermented durian to offset the heat. Sambals are ubiquitous and versatile condiments, popular on countless chicken, fish, salad, and soup dishes, and with crunchy snacks.

Sriracha

Serious Eats / Robyn Lee

Generally made from chile peppers, sugar, salt, garlic, and vinegar, Sriracha traces its origins to Thailand, where it was developed in the 1930s in the coastal town of Si Racha. The variety most commonly found in the United States, Vietnamese-American "rooster sauce" Tương Ớt Sriracha, was developed in California in the 1980s.

In Southeast Asia, Sriracha is commonly used as a dipping sauce for seafood, or as a topping for pho or spring rolls. The "rooster sauce" we know today was developed for similar uses, but has gradually appeared in everything from potato chips to milkshake recipes. At 1,000-2,500 SHU, Sriracha is slightly milder than a jalapeño pepper, with a characteristic vinegary sweetness. Thai Sriracha is usually tangier and runnier than other varieties, but is similarly versatile. For more info on the differences, see our Sriracha taste test (our favorite isn't what you'd think).

The Caribbean

Scotch Bonnet Pepper Sauce

Serious Eats / Ben Jay

Throughout the Caribbean, Scotch Bonnet peppers are the key ingredient in local pepper sauces. (The term "hot sauce" is seldom used in the Caribbean.) Pepper sauces accompany nearly everything—chicken, goat, fish—as condiments to such an extent that they're indispensable to the cuisine.

Jamaican sauces tend to focus mainly on heat, featuring little more than Scotch Bonnet and vinegar (jerk marinades also rely heavily on Scotch Bonnet). Guyanese sauces have a similar composition, but tend to use the local wiri wiri pepper instead of Scotch bonnet. Sauces from the British Virgin Islands are traditionally spiked with mustard, adding another dimension of heat and a trademark yellow color. Trinidadian sauces are a bit more involved, often featuring hotter peppers like Trinidad moruga scorpion (up to 2 million SHU), mustard, and occasionally fruit.

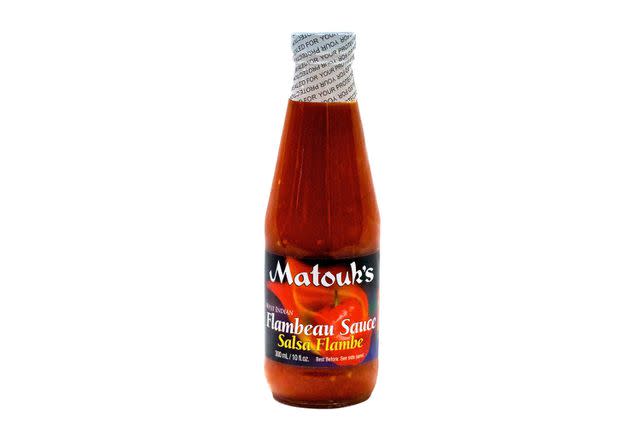

Brands like Matouk's are common in Caribbean supermarkets, and Brooklyn's own Bacchanal Sauce includes pineapple and papaya, but back on the islands, homemade sauces, often sold at roadside stands, are the most popular.

Ti-Malice

This Haitian hot sauce, named for a character in Haitian voodoo, combines heat with a distinct citrus sourness. According to folklore, the mischievous Ti Malice made a particularly spicy sauce to deter his dimwitted friend, Bouki, from eating his food. But the plan backfired when Bouki loved the sauce and raved about it to everyone. Recipes often include onions or shallots, lime juice or sour oranges, garlic, and occasionally tomato, as well as a habanero or Scotch bonnet for heat. It's traditionally served with fried goat, fried pork, or fish.

Europe

Erős Pista

Serious Eats / Ben Jay

Hungarian cuisine is well known for its heavy use of paprika, and its hot sauce is no exception. The brand Erős Pista (Hungarian for "Strong Steven"*) is a simple paste made primarily from two ingredients—minced paprika peppers and salt—and is ubiquitous enough that it's become the generically-used name for paprika paste in Hungary (Piros Arany, or "Red Gold," is another popular brand.) It's used as a spread or is added to stews and soups to provide extra heat. A milder, sweeter variety can be found under the name Édés Anna ("Sweet Anna").

Perhaps named for Szent István király (Steven I or Saint Steven), the first king of Hungary who ruled from 1001 to 1038.

Peri Peri

Serious Eats / Ben Jay

Portuguese in origin, peri peri sauce gets its name from the African Bird's Eye Chile, also known as "piri piri" (Swahili for "pepper pepper"). The pepper is native to southern Africa, including former Portuguese colonies Angola and Mozambique, and was transported by the Portuguese throughout their empire. Today it's strongly associated with Nando's, a chain of casual chicken restaurants in South Africa and the United Kingdom, but peri peri chicken still endures as Portugal's national dish. The sauce's warm flavor, sharp heat, and thick texture also work well in curries (the Portuguese brought the pepper to Goa, India as well).

Peri peri—the pepper—is very hot at 50,000-175,000 SHU, while most peri peri sauces are considerably milder, since the pepper itself is relatively minor ingredient. A bottle of Nando's peri peri sauce includes greater amounts of vinegar, lemon, onion, salt, and serrano pepper, but the peri peri still provides considerable kick.

The Americas

Aji

Serious Eats / J. Kenji Lopez-Alt

Aji has two identities depending on where you are. In Peru, it's a creamy, pea-green sauce slathered over plantains and rotisserie chicken, and it may be better known simply as "green sauce." Recipes for it include ingredients like mayo or sour cream for creamy tang. Grassy green chiles form its base, but at least some of the flavor is derived from the native-to-South-America aji amarillo, a sunny yellow pepper easy available in paste form.

In Colombia, aji is more of a more sharp, chunky concoction of pieces of chile and herbs in an acidic liquid, usually a combination of vinegar and lime juice. Like many Mexican salsa frescas, it includes tomatoes, green onions, and cilantro. But the go-to pepper can vary, from aji to habanero to the round, cherry-shaped rocoto.

Cajun Pepper Sauce

Serious Eats / Ben Jay

Basic Louisiana-style hot sauces usually consist of a thin mixture of chiles, vinegar, and salt, often fermented. Beyond that, anything goes. Most mass-produced brands use cayenne pepper, but different peppers and aromatics are often added in. The most famous brand, Tabasco, relies heavily on a three-year aging process for a funky complexity. Variations like habanero and smoky chipotle have become more popular recently.

Buffalo-style sauces like Frank's RedHot, originally from Louisiana but forever tied to the first Buffalo chicken wings at Buffalo's Anchor Bar, include garlic and go heavy on the vinegar, which accounts for their distinctive flavor (that makes everything taste like wings).

Mexican Salsa/Hot Sauces

Serious Eats / Vicky Wasik

The line between salsa and hot sauce is easily blurred, as salsas can be used in a very un-hot-sauce manner as dips and marinades, but also as post-cook condiments. There are thousands of salsas across Mexico, from fresh chunky mixes of chopped tomato, onion, and chile to roasted pepper purées to intense sauces based on dried chiles.

As for bottled Mexican hot sauces, they tend to fall somewhere between salsa and Cajun-style fermented hot sauce. For instance, Cholula uses arbol and piquin peppers and some vinegar for a deep, musty tang like Tabasco with a lot more dimension; El Yucateco is more salsa-like, featuring habanero, tomato, and no vinegar at all. It's hot and a little fruity, but just as at home on a taco as salsa verde.

Molho Apimentado

Fresh salsas, the kinds with tomatoes, chiles, and perhaps some vinegar and olive oil, go by many names. In Colombia it's aji. In Bolovia, it's llajua. In Chile, it's pebre. And in Brazil, it's molho apimentado, an incredibly versatile sauce that goes on everything from grilled meat and seafood to salads to fejoida, the national dish of black beans stewed with all manners of pig parts (the "completa" frequently uses ears).

The chile of choice varies from region to region and home to home, but in Brazil the sauce is commonly made with malagueta peppers (not to be confused with the unrelated African peppers of the same name). This one is a relative of the Portguese peri peri pepper, and it's also very hot (60,000 to 100,000 SHU), but slightly larger.

The Middle East and Africa

Harissa

Serious Eas / Max Falkowitz

North Africa's most loved condiment, harissa is a thick and smooth but slightly grainy chile paste, made with ground red chiles, spices like cumin and coriander, and a bit of olive oil. It'll add warm, sunny heat to grilled meats, falafel, soups, salads, and anything you can spread it on. Harissa can be readily found at most Middle Eastern groceries, but if you're making your own, try adjusting the blend of red peppers and spices to get a hotter, smokier, or sweeter end product. If you want to temper the heat and add a creamy texture, you can also add harissa to yogurt dips and aioli.

Zhug / S'chug

Serious Eats / Vicky Wasik

Though it's a staple of Israeli cuisine, zhug (also spelled s'chug, and pronounced s-ch-oog with a uvular "ch") was actually invented by Yemeni Jews, who later brought their recipes to Israel. Zhug can be made with red chiles, green chiles, and sometimes tomato, plus some garlic and coriander, and it has a livelier, more pungent heat than harissa. It's most commonly found at Israeli shawarma, falafel, and hummus stands.

Shatta

Serious Eats / Max Falkowitz

Egyptian shatta is also a thick paste made from ground chiles and olive oil, but the addition of a tomato base, parsley, and/or coriander, affect the flavor considerably. Shatta is most commonly served with koshari, Egypt's national dish of rice, lentils, and macaroni. Recipes vary from region to region, with Sudanese shatta omitting the tomato in favor of lemon juice.

Shito

Aka "pepper" aka "shitor din," shito is the Ghanaian cook's way of making the cuisine's unforgivably spicy food even hotter. The most common version is inky black, made with oily dried fish callled momoni, and ingredients like ginger, garlic, and of course fiery chiles. It's spooned over the country's stewy/saucy fare like egusi, a ground seed-based soup, and palaver sauce, a stew of taro greens, egusi seeds, and silky palm oil.