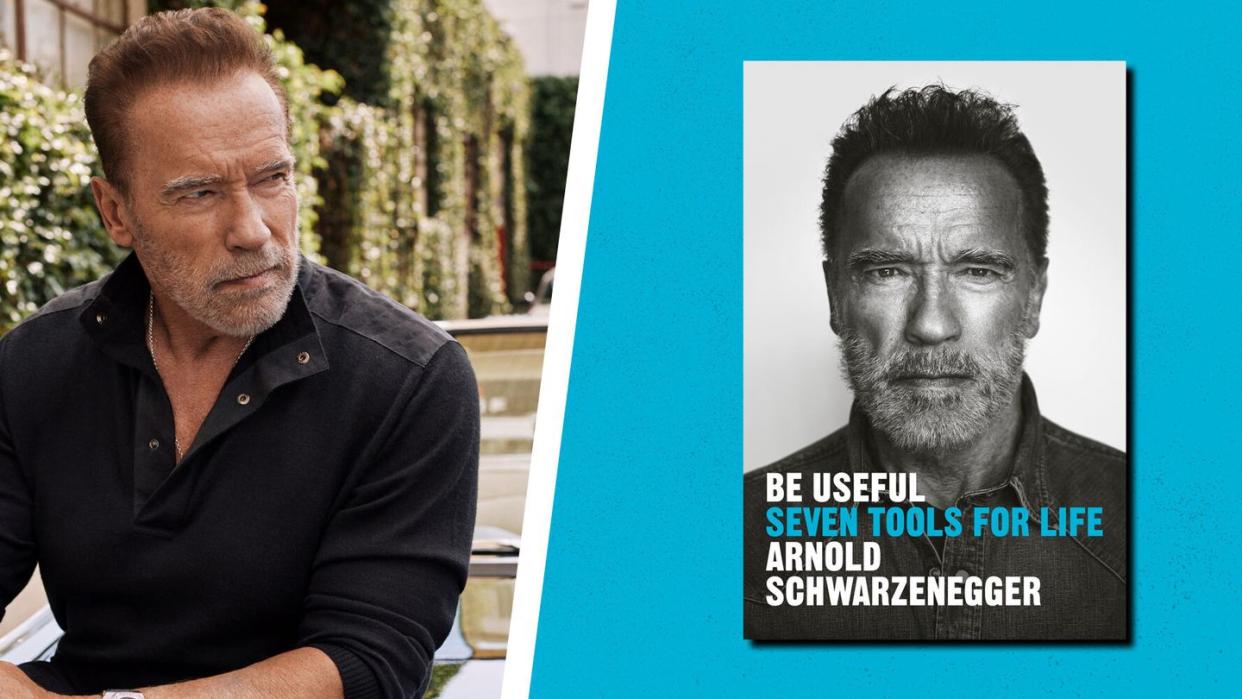

Arnold Shares His Best Tips for Success: 'Failure Is Not Fatal'

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

PEOPLE COME UP to me all the time and say, “Arnold, I didn’t hit the goal I set for myself, what should I do?” Or they say, “Arnold, I asked out my crush and they said no.” Or “I failed this week to get the promotion I wanted, what do I do now?”

My answer to them is simple: Learn from your mistakes and then say, “I’ll be back.”

Often, that’s all the advice people need. They’re just a little scared, or maybe a little desperate, and they need some encouragement to get back on track. But then there are the others, who want to complain that life is unfair because this thing they wanted so badly didn’t happen exactly when they wanted it to, and it hurts too much to think about the possibility that maybe they didn’t do enough of the work to achieve their desired outcome.

I don’t say this with any judgment; I’ve been there. When I lost to Frank Zane in 1968, I was despondent and inconsolable. I cried in my hotel room all night afterward. It felt like the world had come crashing down on me. I questioned what I was even doing coming to America. I was away from my parents, I was away from my friends, I didn’t speak the language, I didn’t know anyone in Miami. I was all alone. And for what? For second place to a guy who was smaller than me?

I blamed everyone and everything else for my loss. The judging was unfair. The judges were biased toward Frank, who was an American. Traveling from London and eating crappy food in the airport days before had affected my body and training negatively. The loss was too painful for me to look in the mirror and admit that maybe I hadn’t done enough to win, that it was my fault.

The next morning at breakfast, Joe Weider invited me to come out to Los Angeles. It was only after working out with the guys at Gold’s over the next few weeks that I was finally able to see the difference between Frank and me, and to admit that he’d won fair and square. I simply wasn’t as well-defined. This was true not just in comparison to Frank, but in comparison to almost all the American guys I was working out with. I was bigger than them, and I had better symmetry, but they were doing something I wasn’t doing that was allowing them to get very cut. If I wanted to be the best, I had to figure out what that was and start doing it myself. So once I got settled in my new apartment in Santa Monica, I invited Frank to come stay with me so we could train together and he could show me a thing or two. To his credit, he accepted my invitation. He stayed with me for a month, we worked out at Gold’s together every day, he showed me the exercises he did to get completely shredded, and then he never beat me again.

'Be Useful: Seven Tools for Life'

Amazon

$19.40

Let me be very clear about something. And this is for anyone out there who has ever experienced failure, which is every single one of us: failure is not fatal. I know, I know, that’s such a cliché. But all positive talk about failure has become a cliché at this point, because we all know it’s the truth. Everyone who has accomplished something they’re proud of, who we admire as a society, will tell you that they learned more from their failures than from their successes. They will tell you that failure isn’t the end. And they’re right. If anything, when you look at it with the right perspective, failure is actually the beginning of measurable success, because failure is only possible in situations where you’ve tried to accomplish something difficult and worthwhile. You can’t fail when you don’t try. In that sense, failure is kind of like a progress report on your path to purpose. It shows you how far you’ve come, and it reminds you how far you still have to go and what you have to work on to get there. It’s an opportunity to learn from your mistakes, to evolve your approach, and to come back better than ever.

I first learned this, like I learned many things, in the gym training for weight-lifting competitions when I was younger. The beauty of weight-lifting is that failure is baked into the practice. The whole goal in weight-lifting is to work your muscles to failure, which we sometimes forget. When you can’t squeeze out that last rep or lock out those elbows before dropping the weight, it’s not uncommon to feel a flash of frustration, but then you have to remember that your failure on that particular lift doesn’t mean you’ve lost somehow. It actually means that your workout was a good one, that your muscles were fully fatigued. It means you did the work.

In the gym, failure doesn’t equal defeat, it equals success. It’s one of the reasons I’ve always been comfortable pushing the limits in everything I do. When failure is a positive part of the game you play, it’s much less scary to search for the limits of your ability—whether that’s speaking English, acting in big movies, or tackling big social problems—and then once you’ve found those limits, to grow beyond them. The only way to do that, though, is to constantly test yourself in a manner that risks repeated failure.

This is how weight-lifting competitions are designed. In a traditional meet, you get three lifts. Your first lift is a sure thing. It’s a weight you’ve done before and you’re comfortable with. The purpose is to get your feet underneath you, to get the butterflies out, and to make sure you’ve put one good lift on the board. Your second lift is a little bit of a stretch: you lift something at or near your personal record weight, with the goal of putting some pressure on your competitors. Maybe you don’t win in the end, but at least you can leave knowing that you’d hit your previous max. On your third lift, you are trying to lift a weight you have never lifted before. You are trying to break new ground—for yourself as a weight lifter and for the state of the sport itself. This final lift is where records are broken and victories are won. It’s also where failure quite often occurs. As a weight lifter, I failed on ten different final lifts to bench press 500 pounds, back when that figure was almost unheard of. Once I finally did it, benching 500 pounds got easier and set me on a course to eventually put up 525 pounds.

That third lift is a microcosm for chasing your dreams out in the real world. It will be hard, and it will feel unfamiliar. People will be watching and judging, and failure is a real possibility. Failure is inevitable in a lot of ways. But when it comes to achieving your vision, it isn’t failure you have to worry about, it’s giving up. Failure has never killed a dream; quitting kills every dream it touches. No one who has set a world record, or started a successful business, or set the high score on a video game, or done anything difficult at all that they cared about, has been a quitter. They got to where they are on the back of numerous failures. They reached the pinnacle of their profession, invented world- hanging products, achieved their craziest visions because they persevered through failure and actively paid attention to the lessons that failure is designed to teach us.

Take someone like the chemist who invented the lubricant spray WD-40. The full name of WD-40 is “Water Displacement, 40th Formula.” It was called that in the chemist’s lab book because his previous thirty- ine versions of the formula failed. He learned from each one of those failures and nailed it on the fortieth try.

Thomas Edison is legendary for learning from his failures. So much so that he refused to even call them failures. In the 1890s, for example, Edison and his team were trying to develop a nickel-iron battery. Over the course of about six months, they created more than nine thousand prototypes that all failed. When one of his assistants commented that it was a shame they hadn’t produced any promising results, Edison said, “Why, man, I have gotten a lot of results! I know several thousand things that won’t work.” This was how Edison looked at the world— as a scientist, an inventor, and a businessman. It was this kind of positive mind set, this sort of brilliant reframing of failure, that led Edison to the invention of the lightbulb barely a decade earlier and to the thousand other patents issued to him by the time he died.

As you think about this thing you want to do, or the mark you want to make in this world, remember that your job is neither to avoid failure nor to seek it out. Your job is to bust your ass in pursuit of your vision—yours and nobody else’s—and to embrace the failure that is bound to come. Much like how those last painful reps in the gym are a signal that you’re one step closer to your goal, failure is a signal of which direction your next step should go. Or like Edison would say, which direction it shouldn’t go. This is why failure is worth the risk and important to embrace: it teaches you what doesn’t work and points you toward the things that do.

Personally, I attribute a number of my successes as governor, including my reelection, to having learned from the failure of the 2005 special election and then using those lessons as a guide for what to do next. The voters told me that bringing my disagreements with the legislature to their doorstep was a huge mistake. They told me that speaking like a technocrat or a policy wonk, instead of like the normal person and the non-politician they’d elected, wasn’t going to work for them. If I wanted to get anything done, Californians were saying, I definitely couldn’t take those approaches again. With their votes, they were asking instead for explanations in plain English, and they were pointing me in the direction of my adversaries, telling me that the solution to my problem was there.

So I listened to them. After the election, I invited the leadership of both parties, from both houses of the legislature, on my plane, and we flew to Washington, D.C., to meet with California’s entire congressional delegation and talk about ways to better serve the people. For five hours in each direction, we sat together in close quarters, forty thousand feet over America, and talked not as political opponents but as public servants with a common cause: helping California’s residents live happier, richer, healthier lives. By the time we got home a few days later, the broad strokes of a number of bipartisan initiatives had been sketched out.

Had I ignored the lessons from 2005, had I chosen to whine about the outcome of the special election, had I vilified my opponents instead of defying political convention and taking responsibility for my policy failures, there’s very little chance that any of this stuff gets done and there’s no chance in hell that I get reelected a year later. It’s not an exaggeration to say that these successes I was fortunate enough to enjoy were the direct result of learning from failure.

From BE USEFUL: Seven Tools for Life by Arnold Schwarzenegger, to be published on October 10th, 2023 by Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright(c) 2023 by Fitness Publications, Inc.

You Might Also Like