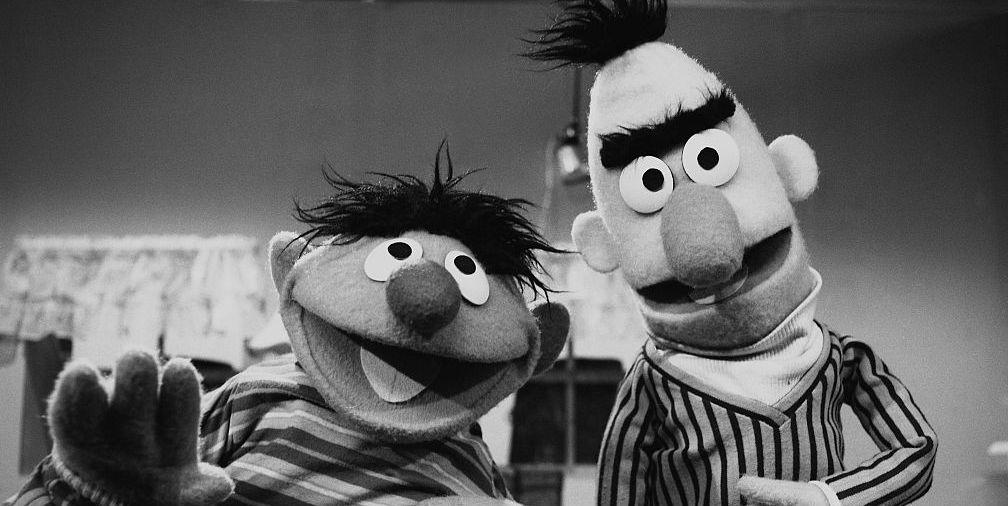

We're Still Going to Keep Thinking Ernie and Bert Are Gay and There's Nothing You Can Do About It

The notion that Sesame Street mainstays Ernie and Bert are more than just confirmed bachelors who split the rent on a cozy urban apartment is not new. Way back in 1994, the New York Times ran an editorial entitled "Are Bert and Ernie Gay?" in response to letters that had been sent in to TV Guide on the subject. Someone was writing to TV Guide (on paper!) about whether two characters from Sesame Street had a timeshare on Fire Island before Troye Sivan was even born. Like the most successful of pop culture ephemera, it's an idea that has animated the imaginations of some and stoked the outrage of others for decades. It came to a head yesterday when, for a brief moment, the internet believed it had confirmation. In an interview published on Queerty, former Sesame Street writer Mark Saltzman said, "I always felt that without a huge agenda, when I was writing Bert & Ernie, they were [a couple.] I didn’t have any other way to contextualize them." The site framed the interview as a coming out announcement and the internet quickly picked it up.

But late yesterday, Saltzman told the New York Times that his comments to Queerty had been taken out of context. "As a writer, you just bring what you know into your work," But, he was notably sanguine about setting down hard and fast rules about the duo. "It’s like poetry. It’s what you need it to be,” he said. It's a striking contrast to Sesame Workshop's strong rebuttal on Twitter:

Please see our statement below regarding Bert and Ernie. pic.twitter.com/6r2j0XrKYu

- Sesame Workshop (@SesameWorkshop) September 18, 2018

And just as quickly as it began, it was over. Or, not really over, just back in the "are they/aren't they" closet in which the couple, excuse me, pair, have lingered for years. Three things, at least, are true here: 1) a creator was sharing his personal experience using empathy to successfully imbue inanimate objects with humanity; 2) a company was protecting its assets from a backlash by bigots; 3) a community got the short shrift.

What glimmered in the possibility of a confirmation about Bert and Ernie was the idea of intentional representation. If the two were canonically gay, those who intuited a deeper relationship would be validated, those who sought to see themselves in Sesame Street could, and the millions of children who were raised on the show would be given the gift of a more inclusive worldview, albeit retroactively. Mark Saltzman's interview suggested that a queer creator had intentionally created queer characters for an international audience. So, it is heartbreaking to come to understand that Saltzman, like many other creators who claim a queer identity, was limited to simply writing and feeling the subtext.

We deserve more than subtext. Relegating narratives that differ from the mainstream to the undercurrent, or worse, to a previously unspoken history, reaffirms that these lives are not as important and should be kept secret. Many hide behind the idea that talking about sexual orientation is equivalent to talking about sex, which is a bad faith argument that's proven surprisingly resilient. Acknowledging sexual orientation as a fact is what happens at straight weddings, the birth of children, the sale of bizarre kid's clothes that say things like "Little Ladies Man", and the gendering of things like Mr. and Mrs. Potatohead (who still have eyes for each other after all these years of monogamous, heteronormative, root vegetable love).

Sesame Workshop responded to the Queerty article by claiming that Sesame Muppets don’t have sexualities, which I suppose is a fine equivocation though it suggests that Sesame Street is a world in which Muppets engage in social structures like apartment housing, grocery stores, and jobs, in which they have personal lives involving friendships, pets, and sleeping, but don't experience romantic affection. This is actually rather dark. On the other hand, Frank Oz, the person behind Bert, Miss Piggy, Cookie Monster and others tweeted that the duo was heterosexual.

It seems Mr. Mark Saltzman was asked if Bert & Ernie are gay. It's fine that he feels they are. They're not, of course. But why that question? Does it really matter? Why the need to define people as only gay? There's much more to a human being than just straightness or gayness.

- Frank Oz (@TheFrankOzJam) September 18, 2018

Well, which is it? My dears, in the Keeping Your Story Straight challenge, you got it all twisted; I’m sorry to say you’re up for elimination. Oz followed up his tweet this morning with a more nuanced mea culpa, writing "Although it doesn't matter to me if someone is gay or viewed as gay, I learned it does matter to a great many people who feel they are not represented enough." This new understanding gets to the crux of the issue: it's not about intellectual property, it's about individuals seeing themselves in the Muppets, something that Sesame Street overtly invites children to do.

If the gay community wants to see itself in Ernie and Bert, we absolutely can and should. At the same time, we deserve better than this and we always have. The fact of the matter is the Bert and Ernie debate shouldn't be a debate. It should be a thing that queer people talk about with each other with little to no straight input.

Here’s the deal: LGBTQ people can say any character that they want is queer. Straight people have no veto power here. Sorry, thems the rules. Why is this? Because of heterosexual privilege. More often than not people and characters are presumed straight until proven otherwise. Straight is the default, which puts LGBTQ people at a disadvantage when it comes to seeing ourselves and feeling included. The best way to correct for that for queer creators to produce canonically queer characters. A secondary, more prevalent correction is for queer people to put queerness wherever we want. We can do that and we’re going to keep doing that. It doesn’t hurt the original property. It’s not like we’re storming Disney World and demanding that Elsa have a girlfriend in Frozen II or else we're shutting down the Matterhorn.

According to the director of "Frozen," it's a possibility Elsa could be getting a female love interest in the sequel https://t.co/X2mK9pik5X pic.twitter.com/CSSx4iKRfn

- billboard (@billboard) March 1, 2018

When the director of the forthcoming sequel hinted that that was a possibility, online reactions were strong on both sides. But we should be beyond hints. It takes no leap of the imagination for an LGBTQ person to read a queer narrative on to a character who does not explicitly claim a queer identity. This is the truth of many LGBTQ people's everyday lives; any person who has ever had to come out does so because they were were once canonically straight. A person who has to clarify the truth about their identity because it is not visible often has no problem offering that gift to a fictional character. The default for queer stories remain predominantly in hints, insinuations, sudden discoveries, and shadowy backstories. Queering popular characters isn't about reclaiming property, this is about our self-conceptualizations. It manifests possibility where there was none.

It's this possibility that animates online discussions about whether Daria was spiritually lesbian; it's the whimsy that led the brilliant John Paul Brammer to declare the Bababdook was gay.

openly gay and with an affinity for hats and drama, the Babadook was the first time I saw myself represented in a film

- JuanPa (@jpbrammer) April 19, 2017

At the same time, LGBTQ people, like all peoples in positions of alterity with respect to a dominant culture, deserve more than having to imagine ourselves into the fictional worlds we're given. And we deserve more than the winking acknowledgment that has come to replace actual presence. Consider J.K. Rowling, who revealed that Harry Potter's Dumbledore was gay in 2007, after the last book in the series was published. While the thought is interesting and seemingly well-intentioned, without textual support it amounts to little more than fan-fiction. And how does it manifest it 11 years later in the forthcoming backstory Fantastic Beasts 2? Director David Yates, when asked if the film would acknowledge young Dumbledore's orientation, replied "Not explicitly."

In the words of actual, explicitly queer icon Ira Madison, III: Keep it.

We deserve more than narrative scraps. We deserve more than revised histories and addenda that reveal a heretofore unknown gay identity. We deserve more than queer afterthoughts (Quafterthoughts®). If art-makers can't create characters that are intentionally queer and indicate that in some way, they don't get points for intention. And they don't get to dictate the terms of use for all the people who engage with the work. Once a piece of art is released into the world, though the creator retains intellectual property rights, they cannot control the imaginations of those who gravitate toward their work.

This is the principle that energizes the fan fiction and fan art markets, of course, but it animates meme, recap, and review culture, as well. It is the driving force behind pop cultural relevance. When a song, a tv show, or a movie character speaks to us, we claim a part of them for ourselves, we think about them beyond the bounds of the context in which they were created. We make them our own. This is right, this is fair, and this is the goal of art. So, in the same way that a couple can claim that a universally beloved ballad is “our song” and set their first wedding dance to it, a queer person can look at a Muppet and say, “I see something of my queerness in this character.” That is not picking up scraps, that is creation itself, that is place-making, that is generation.

I, a black queer person, never thought of Ernie and Bert as gay-I intuited a sibling relationship, which is my right-but I always read Ernie as a person of color. Is this wrong? I don't care. Remember the seminal work The Monster at the End of This Book starring Grover? I always read that as a story about self-acceptance and returned to it when working through internalized homophobia. Is this overreaching? Overruled! Snuffleupagus: walking allegory for erasure and gas-lighting; a representation icon. Count von Count: eccentric persnickety diva; we stan. I could go on all day and that's the point.

The Sesame Street Muppets-and Jim Henson’s Muppets in general-were created as a set of colors with which a great artist could paint and, at the same time, a canvas on which millions of children could create their own worlds. The power of the Muppets comes from the versatility and that duality and, not for nothing, that’s a pretty queer concept. So, for some people-for more than you think-all the Muppets are queer. We don't owe anyone a fight over this. They always have been, they always will be, and there's nothing that those opposed to that interpretation can do about it. In the words of lesbian separatist icon Elsa from Frozen, “Let it go."

('You Might Also Like',)