Antonio Banderas on Death and GIFs

“I went there by myself with $100. I slept on a sofa that had a spring in the middle that was broken,” Antonio Banderas says, pointing at the fully intact couch in the tony Midtown hotel suite where we’re conducting this interview. “It was so strong that it didn't allow me to turn around properly. When I went to a place that didn't have the spring, I continued expecting the spring. I learned how to actually sleep around this thing.”

Banderas is recalling his first months in Madrid, where he moved from his native Málaga at the age of 19 to pursue his dream of becoming an actor. It was just a few years after the far-right dictator Francisco Franco died, and Spain’s capital was swept up in the frenetic countercultural movement known as La Movida Madrileña. Nobody better exemplifies that artistic era than the filmmaker Pedro Almodóvar, who saw Banderas perform in a play and burst into his dressing room afterward to tell him that he should do movies because of his “romantic face.” The encounter proved to be persuasive, and the director cast Banderas in a series of subversive, adventurous films like Law of Desire, Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown, and Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down!

That broken sofa eventually gave way to major international stardom. Hollywood came calling in the early nineties, and Banderas made a name for himself starring in action blockbusters like The Mask of Zorro and Once Upon a Time in Mexico. There was also plenty of family-friendly fare, miles of bondage rope away from the psychosexual world he inhabited in his twenties: the Spy Kids franchise, the suave talking cat Puss in Boots, a CGI bee flitting around and pushing the anti-allergy medication Nasonex. Banderas and Almodóvar wouldn’t work together again until 2011’s The Skin I Live In. They reunited once more for this year’s Pain and Glory, their most meaningful collaboration yet. The film tells the story of an aging, physically ailing director named Salvador Mallo coming to terms with various unresolved emotional relationships from his past. Banderas plays Mallo, a thinly veiled stand-in for Almodóvar, spiky gray hair and all, a performance for which he won the Palme d'Or at Cannes this year.

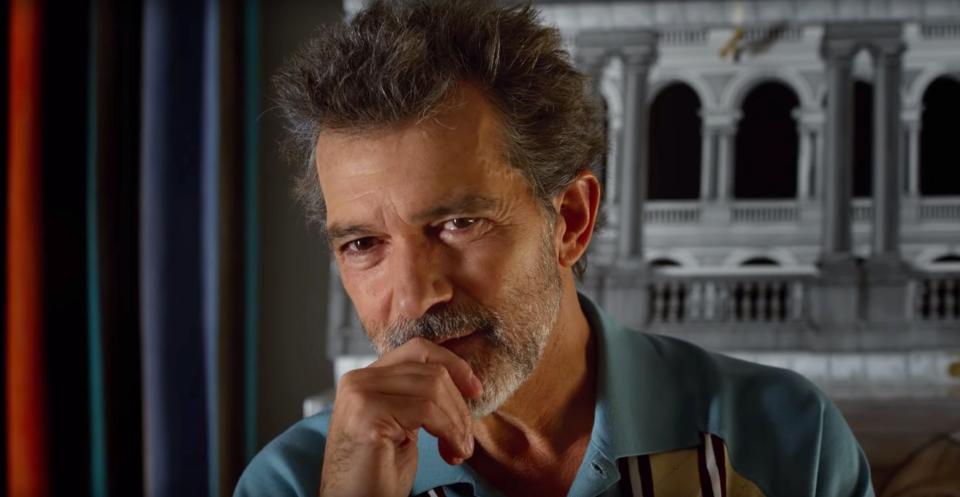

Banderas, who currently lives in Surrey, England, is in New York City promoting Pain and Glory, out in theaters on October 4. He also stars in the forthcoming Stephen Soderberg Netflix movie The Laundromat, a madcap retelling of the Panama Papers scandal. He arrives at our interview in the middle of a whirlwind press day and almost immediately slumps over the table and rests his head in his arms. Banderas is wearing a denim jacket and jeans, with two leather bracelets on his right wrist: One, embedded with a small evil-eye amulet, was given to him by his girlfriend, Nicole Kimpel, a Dutch investment banker. The other, decorated with an engraved silver plate, was a gift from his ex-wife, actress Melanie Griffith.

Two years ago, Banderas, 60, had a heart attack that he says brought renewed clarity to what’s important to him in life. He speaks mellifluously and thoughtfully about everything from the meaning of death and his relationship to the Catholic faith to the personal importance of Puss in Boots. And he even, when asked about the viral GIF of himself at a computer from the 1995 film Assassins, acts it out in person.

GQ: In Pain and Glory, you play a character who's suffering from a host of physical ailments. Did you channel your heart attack into playing that character?

Banderas: There's something Almodóvar detected immediately. He detected that something had changed in me since that cardiac event, and he asked me to not hide it, to use it in the movie. When you have something that happens to you and you see death very close to you, you think very much about your life. Only the things that are really truly important stay at the surface, and you realize that the only certainty that we have is death. That is the only thing that is really perfect. Everything else is relative to many things.

You’re also playing this character who’s in his seventies. You recently played Picasso at the end of his life. You had your heart attack. So you've been thinking about death a lot.

We all know that this is the end of the comedy. For everybody. In one hundred years from now, everybody's going to be bald. This is it. And you know that you have to use every speck of your life to do the things that you want to do. There is only space for the truth. There are no more games. The games kind of disappear, and you just concentrate on things that are really important.

We actors use everything that happened in our lives. I don't play the trumpet. I don't write books or paint. I'm an actor. So all of those things are very difficult to hide, and I don't want to. I thought that this movie actually allows me to create the character in a completely different way than I did before, with other characters. This character was asking me to get in the mud with Pedro. Metaphorically, I had to kill myself in order to go somewhere else.

I read a 1988 interview where you say it's very hard to reach a degree of intimacy with Almodóvar. Now, 30 years later, after having played him, do you still feel that way?

Yeah. For 40 years we've been friends, but Pedro is a very private person, and I knew always that there were boundaries that I should respect. Our friendship has been developed in a very specific universe, and I never tried to trespass those boundaries. I was very respectful with his intimacy, and so, yeah, it was surprising to me when I received the script, to see things there that I didn't know. I didn't know that he wanted to say these things, and I didn't know that he wanted to just apologize. I didn't know that he wanted to close that wound, and I didn't know even that there was a wound there.

Which personally gave me the shivers when I read the script for the first time, because I thought, Oh, my God, he's jumping. He’s just doing this thing of revealing himself, and confessing things through cinema. You know, Pedro without cinema, I don't think he can see that existence.

In the moment that [Salvador Mallo] cannot shoot, he's trying to substitute the kind of drug, which is cinema, for this other one called heroin. But at some point he discovered that this is stupid, the real drug is the cinema.

Yes.

He's got to go back in there after this tsunami of life that comes with the reconciliation with his ex-boyfriend, which is I think a very beautiful scene in which you can see both sides of the coin. You can see the pain, and you can see the glory. The pain of the thing that separates them many years ago and the glory of closing that with a kiss and a smile and saying, you know, We're fine. We're fine. We could look at each other's face. And that is very important. That is very important. Anybody who has had that knows that when you close those things, it produces a relief that is very difficult to explain in your own life and your heart.

That was a remarkable scene. I watched it a few times, and the effect was the same.

It was not planned like that.

Oh, yeah?

We rehearsed that scene very flat. The next day...it was the first shot in the morning, and for whatever reason, it hit me in a way that I wasn't expecting. [Actor Leonardo Sbaraglia] started talking. And it hit me, and I couldn't contain and I was thinking, Oh, my God, Pedro's going to cut. This is not the way that we rehearsed.

I said, "Okay, let's do it again." Pedro says, "No, let's just turn it around." But it's probably the only time that that scene was going to be played that way, because it was not in my plan. I don't know. I don't really know what was the thing that made me so emotional.

You still don’t?

I don't know. I don't know. I've thought very much about that scene and trying just to find what was that thing. And I haven't.

So you worked together for so many years, and then you went off to Hollywood. I was thinking about your directorial debut, Crazy in Alabama, and how Melanie Griffith’s character is a bit of a glamorous Almodóvarian woman, in a way, murdering her abusive husband and carrying his head around and all that. Do you think that either consciously or unconsciously you were inspired by him?

The story was actually Melanie's idea, and somebody offered that to her, and nobody was really there to direct it. It was very eccentric and weird, and it was in a drawer at Sony for years. I read it and I found out there was a lot of fun and eccentric, and it talked about issues that I was interested in. I never thought at the time that it was going to be close to Almodóvar. And I think it's not. For example, he's not interested in politics, and the movies are very political. I don't want to compare myself. I'm more modest than that.

You were a star in Spain before you went to Hollywood. Did you feel at all that you were going from being a big fish in a small pond to a small fish in a big pond?

Well, not because of the acting or because of the magnitude of the place and the mythology about it. The language was very uncomfortable, because you feel handicapped. You go for dinner with some friends, and if they got into a conversation that is very different, complex, it is very difficult for you to get in there. So you look like an idiot, basically like a really simple, shallow person. And so at the beginning it was pretty much like that.

I don't live in Hollywood anymore, but Hollywood is not a place anymore. Hollywood is a brand. And if you are branded with that, it doesn't matter where you move.

Sure.

You are, how do you say it, a Hollywood actor. It was a beautiful, extraordinary adventure in which I went to another country. I saw life in a completely different way. Married, got a beautiful daughter, everything. I wouldn't erase one comma. Nothing of the things that I have done in my life.

I want to actually ask you a question about that time, and I need to show you a GIF for it. Do you know that this clip from your movie Assassins has become very popular online?

Everybody is saying that to me. Yeah. And I know the moment of the movie… [Puts on glasses to look at the GIF on my phone anyway]

He's at the computer.

I got him, the enemy, the person that I wanted, and he was so happy, like... [Banderas acts out the GIF] I don't totally understand this new generation and those memes things and those stuff. It's fun, I guess.

Do you remember shooting that scene?

Yeah, we were shooting in Seattle, and it was at the beginning with my career here. It was about the time that, actually, Melanie and I got together. I remember her and Dakota [Johnson, her daughter] coming to visit at the set.

You also voiced Puss in Boots, and you voiced the Nasonex bee. Is there another animal that you have not voiced yet that you would like to?

No. But what is interesting about that is, actually, I came to this country without knowing the language. So the fact that they call me to do a character just for the use of my voice, not my image, was fantastic, and I love that character for many different reasons. Number one, because I like to do comedy, and I think in comedy is when you find a contrast and decide just to make a big voice for a very little cat. I thought it was very successful, but the thing is that when I got to America, at the beginning, they said to me on the set of The Mambo Kings, "Oh, you're going to stay in America, get ready to play the villain."

Really?

Yeah. "The villains here are black and Hispanics. Those are the villains." And then like three, four, five years later, I got a mask and a hat and my horse. I was a hero in a movie, and the bad guy was blond, he got blue eyes, and he spoke perfect English. And I thought, Hmmm, that's interesting.

But with Puss in Boots, the interesting thing is that the movie is for kids. And the kids are listening to a hero who has an accent, and the bad guy—Billy Bob Thorton specifically—[talks in] perfect English. It's very interesting because it made things change. You send messages that go to the back of your brain—and in this case the back of kids’ brains—for diversity and understanding, that there are no good people and bad people depending on their race or their religion or their social status. So that's why the character was, for me, a little more serious than others.

I was rewatching some of your older movies with Almodóvar—Law of Desire and Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! specifically—one after the other, and realized you play the same kind of psychopath in both.

Law of Desire...he killed a guy, and nobody was upset about that. That was fine. It's absolutely accepted. Nobody's going to say anything in terms of morality about that. But if you kiss another person of the same sex. Oh, my God, it's like, the world's going to just fall around. But when I started thinking about that, it totally made me grow personally to understand the world in a completely different way than the education that I had when I was a kid, in schools.

You went to Catholic school?

I went to Catholic school, yeah.

Are you still a practicing Catholic?

I'm not a practicing Catholic, but I am culturally Catholic. I participate in some ceremonies of my hometown, but they are pretty popular. The Holy Week in Málaga, I participate in that. But that is different. This is a way to connect with the transcendental and the spiritual world without people in the middle.

So you went from doing these blockbuster action films, and lately you’ve returned to smaller films. Were you ever worried that you couldn't realistically go back to doing those?

No, I have no worry about anything really right now. I had my heart attack, and one of the realizations that I had is that the money is just a Machiavellian intellectual process, basically. And so I used, spent it, and I bought a theater in my hometown.

If you were going to make an autobiographical film like Pain and Glory, who would you want to play you?

I don't want to do that. I think it's not necessary for anybody to know my story. My story is very simple.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Originally Appeared on GQ