Which Anti-Obesity Medication Do Patients Stay On the Longest?

Photo Illustration by Lecia Landis for Verywell Health; Getty Images

Fact checked by Nick Blackmer

Key Takeaways

The majority of people who are prescribed anti-obesity medication discontinue the drugs at the one-year mark, according to new research

Wegovy (semaglutide), a newer medication, had the highest rate of patient adherence at one year compared to other, older drugs

Researchers suggest that the more effective an anti-obesity drug is, the longer a patient will likely stay on it

Anti-obesity and weight management medications are still making headlines for their popular use among celebrities and everyday patients alike, but new research has found that certain medications have better adherence rates than others.

According to an article recently published in the medical journal Obesity, the majority of people—about 80%—who are prescribed an anti-obesity medication discontinue taking the drug after one year.

The Cleveland Clinic, which conducted the study, found that 44% of patients filled their anti-obesity medications at three months, and 33% at the six month-mark. At 12 months, only 19% of patients continued with the medication.

Among all the anti-obesity drugs studied, semaglutide (Wegovy for weight management or Ozempic for type 2 diabetes) had the highest rate of patient adherence: 40% of people were still taking the medication one year after they were first prescribed the drug.

“Our findings suggest that patients who receive more effective anti-obesity medications are more likely to stay on them long-term,” Hamlet Gasoyan, PhD, lead author of the study and a researcher with Cleveland Clinic’s Center for Value-Based Care Research, told Verywell.

Related: More Than Weight Loss: How Mounjaro Is Helping Patty Nece Regain Her Mobility

Newer Drugs Have Better Adherence

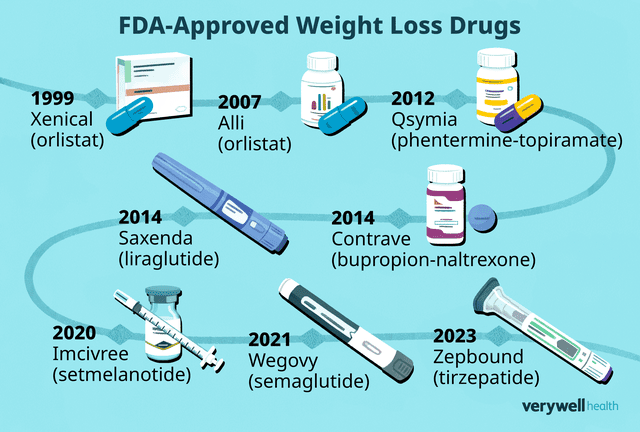

The study looked at different anti-obesity medications, including Qsymia (phentermine-topiramate), Contrave (naltrexone-bupropion), Xenical (orlistat), Wegovy (semaglutide) and Saxenda (liraglutide).

Researchers studied 1,911 adults with a body mass index, or BMI, of 30 or greater who had an initial FDA-approved weight management medication filled between 2015 and 2022. The team analyzed data from the Cleveland Clinic’s electronic health records in its Ohio and Florida locations.

As Gasoyan pointed out, patients who took newer, more effective drugs tended to stay on them longer than patients who were on less effective, older ones. Semaglutide, which patients stayed on the longest, was only FDA-approved for weight loss as the injectable Wegovy in 2021.

A 68-week clinical trial on participants with obesity found that people on Wegovy lost an average of 12.4% of their initial body weight compared to those who received a placebo.

Naltrexone-bupropion, which was FDA-approved in 2014 as a pill called Contrave, was associated with lower odds of patient adherence; only about 10% of patients remained on it at one year, according to the study. Research has found that people on the medication lost 5–10% of their body weight within 56 weeks.

Clinical data on phentermine-topiramate, which was FDA-approved as a pill called Qsymia in 2012, found that about 44–52% of patients lost at least 5% of their body weight over 56 weeks on the medication. About 34–44% lost at least 10%, and 14–29% lost at least 15% of their body weight.

Illustration by Mira Norian for Verywell Health

Why Do Patients Stop Taking Their Medication?

While the Cleveland Clinic study did not ask patients or their healthcare providers why they discontinued their anti-obesity medication, some may have stopped within three months because they could not tolerate the drug or were unsatisfied with the early weight loss results, Gasoyan said.

Known side effects of these drugs vary depending on the medication but can include nausea, vomiting, headache, dizziness, diarrhea, numbness or tingling in the hands, arms, feet, or face, trouble sleeping, and dry mouth.

“Some of the older anti-obesity medications tend to be mild stimulants. They can create a little bit of anxiety or raise blood pressure,” Vijaya Surampudi, MD, an assistant professor of medicine in the Division of Human Nutrition who works in the Center of Obesity and Metabolic Health at UCLA, told Verywell.

“One of the oral anti-obesity medications does have an anti-addiction medicine in it called naltrexone, so you can’t be on any sort of narcotic painkiller [at the same time]. So if someone needs to have surgery, it’s very difficult to actually be on that anti-obesity medicine,” she said.

Related: The FDA Is Investigating Potentially Serious Side Effects of Weight Loss Drugs

Another reason why someone might stop taking an anti-obesity medication is because there’s often a mindset that weight management is temporary, Surampudi said, even though many experts believe obesity is a disease and needs chronic treatment.

“There’s a perception that once you get to a more comfortable weight, you don’t need the medicine anymore,” she said.

While Cleveland Clinic’s Gasoyan didn’t look at specific factors why someone would stop their medication, he and his colleagues did analyze health insurance coverage, and classified participants’ records into private, Medicare, Medicaid, self-pay, and other. They found that insurance coverage can impact how long someone stays on an anti-obesity medication.

“We are seeing reports that U.S. employers are considering restricting insurance coverage for anti-obesity pharmacotherapy, often citing the unsustainable cost burden of the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) as well as the rapid weight gain after discontinuation of treatment,” Gasoyan said.

Other reporting has found that patients might stop taking a weight management drug because a coupon expires and they can no longer afford it.

Related: How to Continue Taking Mounjaro or Ozempic When You Can't Afford It

But, on the other side of the coin, Gasoyan said new data on the health benefits of newer anti-obesity medications could inform future coverage decisions of insurance providers. In other words, the more effective anti-obesity drugs become, the more insurance providers might realize their value.

“Our findings, along with future studies on determinants of non-persistence with anti-obesity medications, could offer opportunities for more nuanced insurance benefit design, incorporating evidence-based usage management tools, rather than limiting or eliminating anti-obesity medications coverage altogether,” Gasoyan said.

Promising Drug Regimens Are Ahead

Gasoyan’s research did not include Zepbound (tirzepatide), which was approved for weight management in November. Zepbound is now considered one of the most effective anti-obesity drugs on the market, contributing to an average of 26% weight loss over 88 weeks. Even at just 36 weeks, patients experienced an average weight reduction of 20.9%. Experts think this could improve patient adherence: If people see results, they’ll be more inclined to stay on the drug.

“In our study, patients experiencing greater medium-term weight loss had higher odds of later-stage persistence, independent of the anti-obesity medication,” Gasoyan said. “This gives us grounds to hypothesize that long-term persistence with more effective anti-obesity medications, such as tirzepatide, could be even higher. We plan to examine this question in our future work.”

At the end of the day, Surampudi said that if a patient isn’t happy on a specific medication, it’s up to them and their healthcare provider to find a treatment strategy that works best for them. If side effects are too much with a specific medication, for example, there are other ways to manage obesity.

“In order for any sort of intervention to work, it requires a lot of participation on the person’s end as well—they have to feel good about their choices. So I will support a patient any which way and try to help them achieve their goals,” Surampudi said. “If they don’t feel that this is the right medicine for them, we will work a different strategy.”

What This Means For You

New research out of the Cleveland Clinic found that about 80% of patients prescribed an anti-obesity medication stop taking the drug within a year. If you’ve been prescribed a newer medication, such as Wegovy or Zepbound, odds are you’re more likely to keep up with your doses. Researchers suggest that the more effective the drug is, the more likely a person will be inclined to stay on it.

Read the original article on Verywell Health.