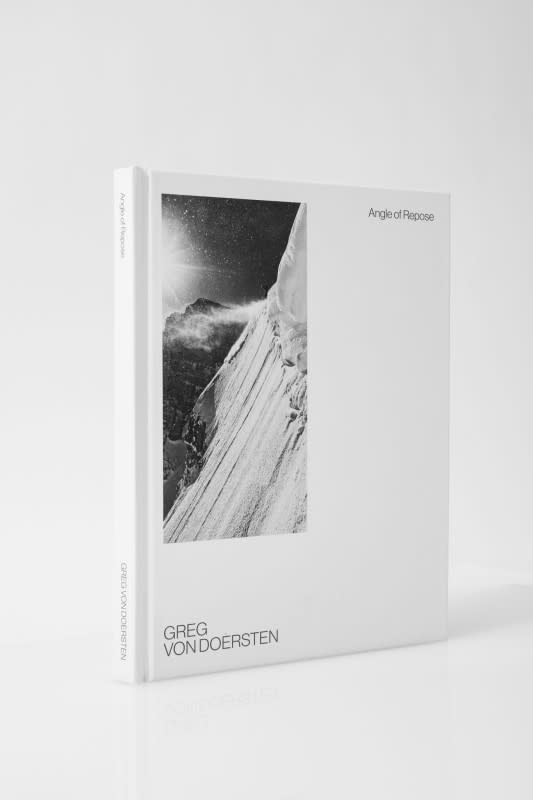

Angle of Repose—A Lifetime of Gravitation in the Tetons

A Lifetime of Gravitation in the Tetons

Words and Photos by Greg Von Doersten

It was a beautiful bluebird powder day off the backside of Snowbowl, Montana. A storm had deposited 10 inches of low-density snow and I was excited to drop into the run. As I approached the ridge, I noticed a point slide trickle from my skis down the slope. It fanned out, setting off a chain reaction of bigger slides that fascinated me. My ski partner, Ed, an experienced snow scientist for the U.S. Forest Service, stopped me and said, “Welcome to backcountry skiing, Greg. You have just witnessed an important lesson in physics and snow safety.”

He termed it, “angle of repose,” which I later learned is a scientific formula. In simple terms, it is the maximum angle at which a loose solid material will remain in place. Anything beyond the angle of repose, and those grains will start to slide. This angle will change based on a variety of factors and are different for various particulate substances. Ed went on to explain that the angle of repose for snow is around 38 degrees.

During the 80s in the U.S., very few people were accessing the backcountry, and ski touring was relatively new. It became as integral to my work as solid partners and good light. Ski touring and mountaineering allowed me access to pristine slopes and scarcely seen landscapes that exist beyond the ski area boundaries—to capture the moments we as skiers dream of. Doing so, however, requires you and your teammates to engage in a delicate dance with the angle of repose. As winter sports photographers, we constantly evaluate snowpack, slope aspect, and temperatures, searching for the snow and terrain that delivers exceptional photographs. We do this while respecting the principles of the physics equation. When done well, the entire team returns home safe, with a catalog of the iconic work that has become associated with my name.

Photo: Greg Von Doersten

The Grand Teton, Wyoming.

Photo: Greg Von Doersten

Morning shift.

Photo: Greg Von Doersten

Top of the morning.

Photo: Greg Von Doersten

Mountain ops crew digs a trench for the tram on February 22, 2017. The resort received 148 inches in February that year, and finsihed the season with 593 inches. Both records.

Photo: Greg Von Doersten

Corbet's Cabin.

Photo: Greg Von Doersten

Jackson Hole local, Forrest Jillson finding his roots on a big day.

Photo: Greg Von Doersten

Max Hammer at the angle of repose.

Photo: Greg Von Doersten

Todd Ligare drops the wall of the S&S couloir.

Photo: Greg Von Doersten

Vapor trail with Malachi Article.

Photo: Greg Von Doersten

Jackson Hole backcountry ski guide, Dave Miller on No Shadows.

Photo: Greg Von Doersten

Nick Keefer. Jackson Hole backcountry.

Photo: Greg Von Doersten

Mikey Marohn and Halina Boyb mind surf the possibilities.

Photo: Greg Von Doersten

Caite Zeliff hikes toward Pucker Face.

Photo: Greg Von Doersten

Legend of legends, Doug Coombs.

Photo: Greg Von Doersten

Arianna Tricomi, crystalized in the Jackson Hole backcountry.

Photo: Greg Von Doersten

Tristan "Teton" Brown lays one out in his namesake range.

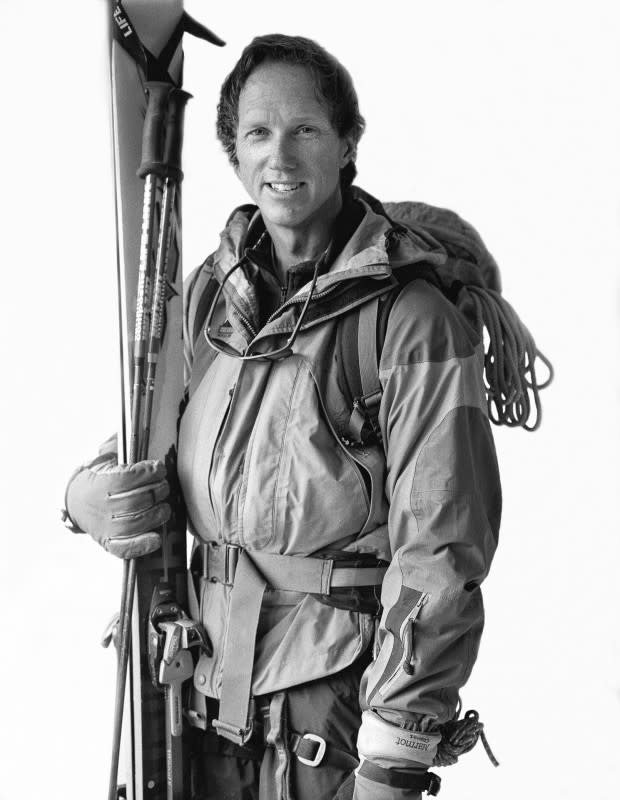

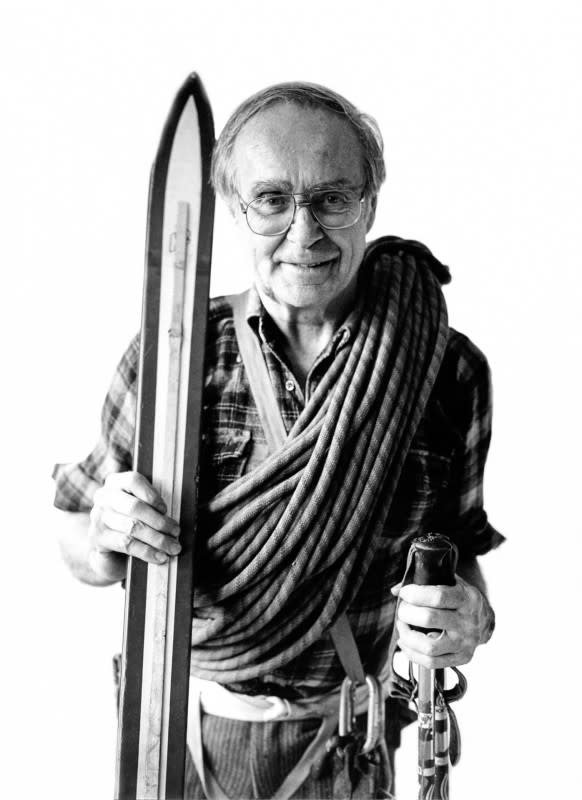

Photo: Greg Von Doersten

The Man. Bill Briggs with the equipment he used to make the first ski descent of the Grand Teton in 1971.

Photo: Greg Von Doersten

Big air maestros, Owen Leeper and Julian Carr in the Caribou-Targhee National Forest

Photo: Greg Von Doersten

Tim Durtschi floating through a portal.

Ski touring, of course, is not what it was in the 80s. Lightweight gear with locking AT bindings has opened up the backcountry to a whole new class of skiers. Similarly, fully automatic digital cameras have eliminated the need to follow focus manually and read light and exposure. We no longer need to wait for a return package from the lab to find out if we “got the shot.” In both cases, innovations in technology slightly altered the proverbial angle of repose and created an avalanche of access and participation. In the process, some of the nuance and art have been washed away.

The angle of repose moment in my career, the single grain that plummeted and started a snowball effect, came in the mid-90s. I was asked to be a senior photographer at Powder magazine. It was a small gesture, the placement of my name on a masthead, yet was the pinnacle of achievement in ski photography, opening doors to world travel, and access to the best athletes, writers, and film production companies. Sadly, we no longer wait for a curated collection of the best ski images to arrive in the mail as often. We share our work instantly on our various digital channels where they are consumed on tiny screens, not glossy pages that you can hold, feel, and smell.

The purpose of Angle of Repose is to give these photos—these collaborations between artist, athlete, weather, environment, and mountainside—a proper showcase. Perhaps by appropriately exhibiting these pieces of what I consider fine art, we can help tilt the axis once again.

Purchase Greg Von Doersten's timeless "Angle of Repose" book and fine art framed prints HERE!