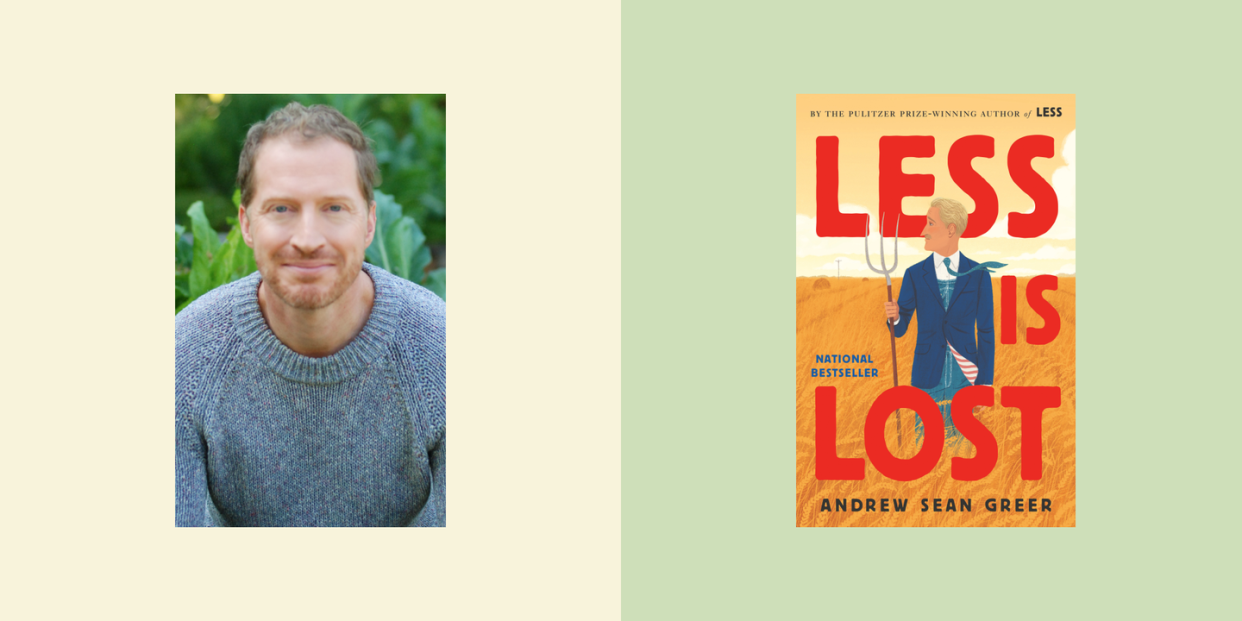

Andrew Sean Greer’s “Less Is Lost”: A Love Letter to a Gentler America—with a Big Finale

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Andrew Sean Greer’s new novel performs an astonishing magic trick: It makes you forget the state of the world—or, more specifically, America.

In Less Is Lost, we return to Arthur Less, “our Minor American Novelist,” and his partner, Freddy Pelu, with whom he’s spent nine months of “unmarital bliss” on top of the nine years they’ve known each other. This is a story, we are told, of a crisis in their lives: how to keep choosing each other when the freshness of love has, if not soured, perhaps staled. In the midst of this crisis, the death of Less’s ex-lover throws the couple into financial distress, forcing Less to accept a series of improbable literary opportunities across the U.S. in order to keep their home.

Writers may take special pleasure in Less Is Lost for the way it holds a mirror to the unique humiliations of their vocation. (At one point Less is asked to “open” for a delayed, famous sci-fi author, whose fans interrupt Less’s attempts to read by chanting the other author’s name.) But with the wit and warmth that made readers fall in love with Less, Greer can find the absurd in everything. A literary prize committee, of which Less is a part, “is never to meet in person; their meetings are incorporeal, like those of angels.” In Dolly, the black pug who accompanies Less for much of his journey, Less recognizes himself—in her passionate effort to shape her towel into a bed each night, she is a fellow artist (“though more successful in her chosen field”).

What made Less such a deep joy to read was the voice—a playful almost-omniscience that occasionally shifted to reveal a mysterious first-person who looked upon Less with unmistakable fondness. That narrative voice resumes seamlessly in Less Is Lost, with Freddy introducing himself early, then weaving in and out of the story: “Now it is my turn to be uncertain. What other infelicities has Less hidden, forgotten, mislaid? What future is there with such a man?”

Though Freddy himself is physically absent for most of the novel, his voice is what gives the book its life, and his central dilemma is the lens through which the story is told. At times he invites us into Less’s consciousness (begging the question of how much of the story is faithfully reported—by Less to Freddy and by Freddy to us—and how much is imagined, reconstructed…and whether it matters). Other times, the narration pulls back: “How long can a gay man survive in the desert? We are about to find out, for, from our buzzard’s-eye view of California, we see an old conversation van painted a pristine shade of green tottering through the night through the Mojave Desert.” And still other times it shifts to second-person, with direct addresses to either the reader or to Less: “Sleep well, my love. More than a continent lies between us tonight.”

Off-screen, Freddy is nursing his hurt at Less’s description of their relationship—uncertain. When he addresses Less in the narration, there is both a hopeful blurring of boundaries between them and a reminder of our separateness from those we love. Less can no more hear Freddy’s commentary than someone in a horror move can hear the viewer shouting, “Look behind you!” Yet the very act of constructing this story can only be an act of love: “that magical spot where the rivers meet, a tessellated surface not unlike a backgammon board where the clear and muddy waters coexist but refuse to mix.”

Less Is Lost is a love story, but it’s also about how we make art—which is to say, how we make meaning: of ourselves, each other, our lives. At his ex-lover’s funeral, Less encounters a Czech editor who praises the poet’s “Beckett sensibility. That things are broken, in shards, that being human means nothing, that memory is nothing, that love is nothing.” Less tells the editor he’s got it all wrong. And indeed, the novel feels like an indictment against this very sensibility.

Less’s road trip is characterized by moments of deep human connection, subversion of stereotypes, and jaw-dropping natural descriptions. (Joshua trees are “Holy rollers at a revival, lifting their heavy arms. How long has this been going on? For all time? Why did no one tell him?”) In the South, where Freddy warns Less they “kill queers” and “being white might not be enough,” Less dons a handlebar mustache and affixes half a dozen American flags to his conversion van. But Less encounters only kindness, which won’t feel realistic to every reader. Then again, our narrator notes, “Well, my darling, the world is so constructed that men like you will always end up safe in bed. Almost always.”

“Pay attention,” Less’s ex-lover instructed Less when his mother died. “You have to write it down. You have to use it later.” Less is enraged at the idea of using his mother’s death as a writing exercise, but he is reminded, “It’s not for yourself. It’s for someone seven hundred years from now.”

Greer pays attention. And if it’s painful for him, as it is for Less, he also transmutes it into something that may survive the next 700 years: “the restorative tonic of a funny tale.” In times like these, that feels like a gift.

You Might Also Like