The Anatomy of the Semicircular Canals

The Three Tubes in the Inner Ear That Regulate Balance

Medically reviewed by John Carew, MD

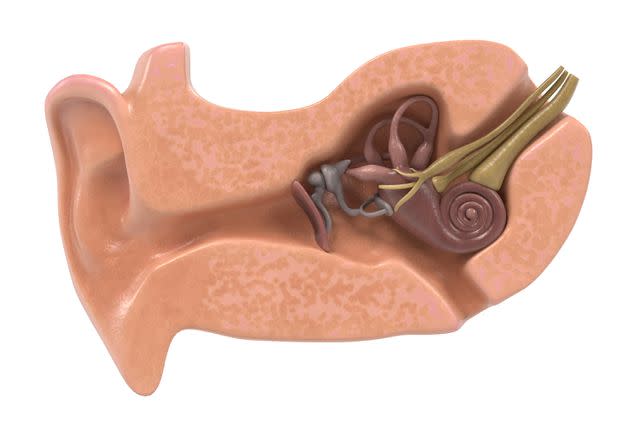

Located in the inner ear, the semicircular canals are three very small tubes whose primary job is to regulate balance and sense head position. They’re considered part of the vestibular apparatus of the body.

Along with the cochlea (organ associated with hearing), they’re positioned in the bony labyrinth, a series of cavities in the temporal bone of the skull.

3drenderings / Getty Images

The three semicircular canals—the anterior, lateral, and posterior—are filled with fluid that remains in position as you move your head. As such, each one provides specific information about body position and balance, helping to ensure that vision remains stable despite motion and coordinating overall activity.

Given this essential function, disorders of the semicircular canals have serious implications. These include motion sickness, as well as several kinds of vertigo, nystagmus (rapid, involuntary eye movements), and a persistent state of dizziness.

The function of these structures—as well as the vestibular system as a whole—can be tested with the caloric reflex test.

Anatomy

Structure

There are three tubular semicircular canals. Inside each of these tubes is a fluid called endolymph, which stimulates hair cells located inside a cluster of nerves called the crista ampullaris.

Each semicircular canal arises from and terminates in the vestibule and is angled on a specific plane. While their lengths vary slightly, each forms a loop with a diameter of 1 millimeter. Here’s a breakdown:

Anterior semicircular canal, also called the “superior” canal, is vertically positioned in a manner dividing the right and left parts of the body. It runs perpendicular to the petrous part of the temporal bone (a pyramid-shaped bone between the sphenoid and occipital bones of the back of the skull).

Lateral semicircular canal is angled at about 30 degrees to the horizontal plane, which is why it’s sometimes called the “horizontal” canal. The lateral semicircular canal is the shortest of the three.

Posterior semicircular canal is oriented on the frontal plane, which vertically divides the front and back sides of the body. It’s also known as the “inferior” semicircular canal.

Ampullae are widened areas at the terminus of each semicircular canal, and each contains a crista ampullaris and a cupola, a structure associated with sensations of balance.

Location

The semicircular canals are located in special, semicircular ducts in the bony labyrinth of each inner ear. These ducts are located in the petrous part of the temporal bone, which are paired bones at the sides and base of the skull.

They basically hang above the vestibule and the cochlea, the snail shell-shaped organ that’s connected to it. The canals have nerves running to the vestibular ganglion (a bundle of nerves), eventually reaching nuclei (receptor regions) in the upper spinal cord.

Anatomical Variations

As with other parts of the inner ear, the semicircular canals can experience congenital deformations. Three malformations most commonly affect these structures:

Semicircular canal dysplasia: This is an inherited under-development of these structures. This occurs in about 40% of those who experience malformation of the cochlea. This condition is associated with the congenital conditions Down syndrome, CHARGE syndrome, and Goldenhar syndrome.

Semicircular canal aplasia: This is characterized by a complete absence of the posterior semicircular canal, which occurs in certain birth defects affecting the cochlea and vestibule. This is typically accompanied by severe hearing loss.

Semicircular canal dehiscence: The walls of any of the three of the semicircular canals may become thinned or weakened, which can create a “third window” into the inner ear, causing endolymph to leak there. Some may experience auditory symptoms, including the Tullio phenomenon, in which loud noises cause vertigo and nystagmus. Others may have longstanding dizziness.

Function

The semicircular canals are primarily associated with sensing the rotational position of the head. Due to inertia, movement of the endolymph lags behind head movements, stimulating hair cells to provide signals crucial for regulating body position and maintaining stability.

The activity of the canals is complementary—head movements cause increased signaling on one side of the head while simultaneously inhibiting those from its counterpart on the other.

This allows for better oculomotor function (smooth motion of the eyes), making for stable vision despite turns or twists of the head. This is the reason you sense your own head nodding or tilting and don’t perceive everything you see as tipping over.

Along with the otolithic organs (the utricle and saccule of the vestibule), the semicircular canals are essential for proprioception (the sense of the body in space and while moving) as well as balance.

This information is sent to vestibular nuclei in the brain stem, which relay this information to other parts of the brain associated with movement and coordination.

Associated Conditions

Disorders or problems with the semicircular canals can certainly be disruptive. These structures are affected by a number of conditions, including:

Motion sickness: This very common condition, in which you feel sick or nauseous while in a car, boat, or other vehicle, can result from activity in the semicircular canals. Among other causes, it can result from diseases or disorders impacting the inner ear.

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV): This condition causes very short-lived vertigo, defined as dizziness and inability to maintain balance whenever you move your head. It also causes nausea and vomiting.

Ménière’s disease: Characterized by vertigo, tinnitus (ringing of the ears), and fluctuating hearing loss. This is caused by a build-up of fluid within the inner ear, impacting the semicircular canals.

Nystagmus: This is when your eyes make uncontrolled, rapid, and jerky movements. It is a physical manifestation of a vestibular disorder, not a condition in and of itself.

Tests

Primarily, the semicircular canals are associated with tests of the vestibular system overall. Therefore, they’re associated with assessments of oculomotor function, balance, and proprioception. Three tests are typically performed in the clinical setting:

Caloric reflex test: To examine the vestibulo-ocular reflex, this test involves squirting a syringe of water into the ear. Differences between the water temperature and the endolymph create an electrical current, which spurs rapid eye moments. As such, this test can determine if there is damage to certain portions of the brain.

Head impulse test: In cases of sudden onset vertigo, the function of the semicircular canals can be tested by applying electrical signals to the sides of the head while tracking eye and head movements. By measuring reactions to these stimuli, doctors can isolate the causes of the condition.

Video head impulse test (vHIT): A more recent vestibular function assessment is vHIT, a technologically advanced head-impulse test. It most often is employed to determine causes of vertigo. In the test, patients wear special goggles and are asked to look straight ahead as impulses are delivered, testing each semicircular canal plane.

Read the original article on Verywell Health.