Amy Grace Loyd and the Mystique of the Migraine

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

“At what cost do we want to be cured of who we are, pain and all?”

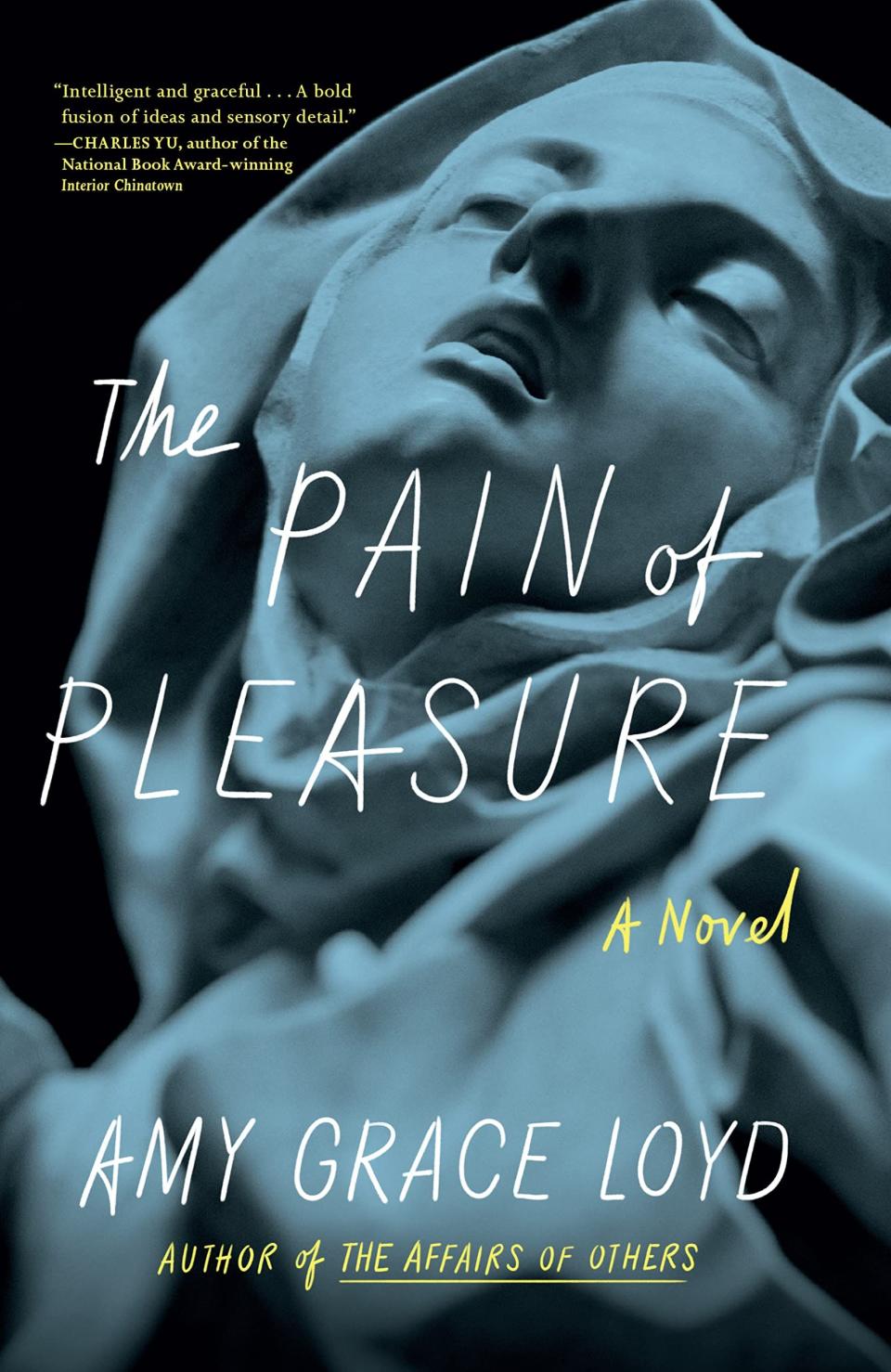

In Amy Grace Loyd’s The Pain of Pleasure, sufferers from all walks of life plumb the depths of this provocative question. Loyd’s sensational second novel, set at a headache clinic located in the basement of a deconsecrated Brooklyn church, explores how our pain does (and does not) define us. Here, a disparate band of lonesome and questioning people coalesce around chronic migraines. At the head of the clinic is the Doctor, a diligent and duty-bound scientist outrunning troublesome ghosts—like Sarah, a former patient who has gone missing. The Doctor is uncomfortably beholden to Adele Watson, the clinic’s wealthy and domineering patron, who rightfully suspects that the Doctor’s feelings for Sarah were more than professional. Mrs. Watson hires Ruth, a tortured nurse running from her own ghosts, to spy on the Doctor and seize Sarah’s journal, still in his possession, which details her erotic misadventures with a married man. Underpinning it all is the threat of severe weather; as the tenuous bonds between the characters threaten to come undone, so, too, does New York City.

Loyd, formerly the literary editor of Playboy and Esquire, can understand her characters’ agony, as she also suffers from chronic migraines. But she intended that The Pain of Pleasure would cut to the quick rarely addressed by medical professionals; as she tells Esquire, “I wanted the book to be about not just physical pain, but the emotional pain that we all have, whether we're willing to admit it or not.” With this fevered tale of addiction, eroticism, and obsession, she accomplishes her mission. Sensuous and seductive, decisively literary in style, The Pain of Pleasure strikes an immaculate balance between its many arresting pleasures of language, which stop the reader cold on the page, and its enticing mysteries, which keep the pages turning. Expect to emerge dazed and dazzled—and to go out searching for your own strange community.

Loyd Zoomed with Esquire from her home in New Hampshire to discuss the mysteries of science, pain, and being alive. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

ESQUIRE: How did you navigate the many points of view in The Pain of Pleasure?

AMY GRACE LOYD: A lot of people didn't want me to have multiple points of view in this novel. But I thought it was important, because we're all locked in our own silos right now, so interior fiction seems all the more applicable. We're all understandably stuck thanks to the pandemic, but also thanks to these roiling political points of view. Sometimes we’re afraid to share because we think we're going to get in trouble if we speak our minds. In our culture right now, there's a taking down and reassembling of the status quo—and that must be done. But I wanted to write a white guy who’s trying to be a good guy, and I wanted to write a woman who’s a villain, although she's a likable villain. How these personalities collide was very interesting to me, because that's happening all around us and playing out on the news.

$16.95

amazon.com

Did any of these characters have a particular grip on you?

Initially, the Doctor did. I remember an agent said to me, “There's a lot of white male in this book, Amy, and that's kind of worrisome.” I said, “Funnily enough, if there’s a character in the book that I identify with the most, it's probably him, because he's trying to fix things that are unfixable.” Migraines are not curable, at least at the moment. Any honest neurologist will tell you, “I can treat it, but I can't cure it.” But the doctor can't help himself. He sees people in pain and he wants to fix it. His relationship to duty is so great that it thwarts his ability to exercise healthy desire—he's in love with his patient, and he cannot allow himself to go there. That mystery—can we or can't we control our own impulses?—is being played out big-time on our national stage. I felt for him because there's a loneliness in those super duty-bound people. I wanted the book to be about not just physical pain, but the emotional pain that we all have, whether we're willing to admit it or not.

Given the medical limitations of treating pain, how do we begin to approach a solution?

There’s so much mystery about migraines and the brain science associated with them. But what I find fascinating is that there are any number of migraine sufferers who were treated with opioids for years. The answer to pain in this country is usually drugs, and for a long time, it was really addicting drugs. Our desire to outrun pain can sometimes lead to more pain. Part of what this book is about is to drag that pain out into sunlight, create room around it, find a community, and find other solutions for your unique body. We each have a unique system—you’ve got to find the keys to it, and doctors can only go so far.

The Pain of Pleasure brought to mind another recent book: The Invisible Kingdom, by Meghan O’Rourke. There’s a connective tissue between these two books—we're seeing major shifts in the literary landscape around chronic illness. How would you like to see that landscape continue to evolve?

God bless Meghan for that book—what a smart book. What I’d like to see is more community around chronic illness. We need to be gentler with ourselves and have more nuanced conversations. When we find a remedy, we think everybody should have that remedy. “You’ve got to try this—it fixed me, so it’ll fix you,” we say. But sometimes it doesn't. We need an openness to this wide range of experiences. I think that's about management of fear, because what’s our first response to pain? Fear. We shouldn’t necessarily go right to the solution-offering, but to allowing for the experience, which literature does so well. In the listening and in the storytelling, there's remedy.

I was so impressed by the long interludes where we sink into the doctor’s perspective, which is rich in neurological and pharmacological detail. How did you approach the task of writing convincingly from that perspective?

I did so much research. I interviewed doctors and neurologists. I read some great books on neurology, too. The difficulty with so much that goes on in the brain is that we can't see it while it's happening. It's very hard to induce a stroke and then watch it. I'm always struck by all the people who tell me, “I don't read fiction because I like to learn things from the books that I read.” They’re going to learn a lot from this book—about brain science, pain science, and climate science. Science increases the mystery of being alive. It goes right to the divine, because how can our brains be so intricate? We’re these enormously complex machines, but our conversations about ourselves often land on, “We’re horrible.” There's a terrible shame in being human these days—what we’ve done to the planet, all these political problems, these wars—but how we exist in these complex machines is astounding and beautiful. It’s a gift. Certainly the pain is a curse, but how could there not be misfires with so complex a body?

Many of these characters long to be healed, but in the absence of a cure, what’s the importance of being adaptive to where they’re at?

I'll tell you a story. When I worked at the New York Review of Books Classics series, we reissued an amazing collection of stories called Nights in the Gardens of Brooklyn, by Harvey Swados. Nobody knew Harvey back in the day because he was associated with being a socialist, and nobody liked polemical writing. When we put it back in print, we approached Grace Paley to write the introduction, but Grace had breast cancer and wasn’t able to do it. So I proposed that I would come to her, record her, and write it in her voice. She agreed to that, and she was amazing. Grace didn’t feel well, but she sat down with me and she did it, because it was so important and it made her feel better. It made her feel connected to someone—Harvey had been her mentor at Sarah Lawrence years before. We had this beautiful experience that stopped time. She ended up taking the piece back and putting it more in her voice, which was great. She died not long after that. We were able to honor Grace's relationship with Harvey by being adaptive.

To your point about bringing pain out into the sunlight, I think it's wonderful that you created a space for Grace to exist in a professional context while feeling unwell. So often, we have to stuff our suffering in the closet.

I was pretty young. I must have been in my thirties, but I wish that I’d been mature enough to take her in my arms. Grace was an activist—she was not bougie at all. Her apartment was a flop house for people who just needed to sleep. Maybe they were coming to New York for a protest, or maybe they needed somewhere to write. She’s long gone, but I still say, “Oh, Grace, what would you be making of these times?” She’d be out protesting, that’s for sure. She was a good person. One of those writers who lives up to your hopes.

$8.49

amazon.com

Why was it important to you to publish The Pain of Pleasure with a small press?

I took a risk, publishing this in an independent way. I know the obstacles that are out there, and I know the pressures on editors right now in terms of how much money a book has to make to justify not only the publication of the book, but their salaries. I wanted to remove the book from all that. I wanted to say to myself—and this is what I think all artists have to do—"I honor this. I value this. It comes with my authority and my permission.” No matter what you do in this life you have to ask yourself: what are your yeses and nos? What’s your authority versus whatever authority you feel bearing down on your head? I keep trying to figure out ways to create a place for people’s words and ideas—a platform for people who want to get their work out, a place where agents and small publishers can find it, or writers can self-publish. But how would I fund it? We can have some community, but funding is another question.

One of my favorite story structures in fiction is when there’s a sense that the outside world is closing in on the small-scale drama. Why was extreme weather the perfect pressure cooker for The Pain of Pleasure?

Living in New York too, we feel that all the time—we feel like part of a bigger story, even as our own drama is happening. That happens in all our lives, but I think in places like New York, it’s really pronounced. New York also has very fragile infrastructure; it’s surrounded by water and the waters are rising. I wanted the weather to be one of those things bearing down on our inner lives. As we all know, the weather can make us feel like shit. It isn’t just migraines—people suffer from arthritis, allergies, swelling. It’s amazing to me that we're not more willing to make more sacrifices to the climate, given how much it affects us.

It's such a reminder of our human smallness. But at the same time, the day the skies went orange in New York, plenty of businesses remained open. As a society, we’re unwilling to say, “It’s just not a good day. Let’s stay home.”

There are going to be more of those days. Like with pain, we just want to deny it. It’s an amazing act of architectural denial. I mean, we're creating these great structures of denial around what it means to be human, especially these days. New York is already a pressure cooker—then the air turns orange, then the subways flood, then there’s sewage in the streets when it rains. As a character says in one of the Weather Report chapters, “New York is a city that can’t handle its own shit.”

But we’re so ingenious. When I get really depressed, I make a list of all the people I find so impressive, and all the things we've done throughout history that are so impressive. We forget because we're biologically trained to see the dangers and the threats—that's how we survive. But unfortunately, an outgrowth of that is how we're also trained to see the dark stuff, the sad stuff, the deprivations, the injustices. We tend to see our grievances more than we see the possibilities. Literature shows us both. At one point in the book, The Doctor says, “There's nothing more vivid for the brain than pain. It's probably the brain's most vivid experience.” But then he also says to Ruth, “So is joy. How can I get you to cultivate your joy?” He's trying to get them to create other things around this pain. Not just drag it into daylight, but pull it wide. You’re not your pain—you’re so much more. You are your good days. You are the things that work. You are overcoming. You are all those things, if you can but allow it and develop the language for it.

You write in the acknowledgements about how “chronic migraines are an altered state,” and how since 2016, we've all been living in a kind of altered state. I'm always interested in how the real world seeps into the creative project. How did that altered state of American life shape this book?

It gave me courage to write something that's kind of unusual, because suddenly, it wasn't just migraine sufferers. We were all suffering. So many of us were sick, and so many of us were lonely. So much of this book is about finding community, even if it's not your ideal community. Because of our experience with the pandemic, we were all stuck in our own interior loops. That gave me courage to write the book the way I wrote it. At one point in the book, the characters are gathered together because of a storm coming. I thought, “What an opportunity. Here's us.” In this country, the story is our individualism—it’s the triumph of the American individual over adversity. But I think increasingly the story has to be, “How do we form a collective, allow ourselves to be different, but still exist in a space together?” Some people might think that’s hippy-dippy. But after all we’ve been through, I think it’s common sense. To say otherwise just means you're going to make it harder on yourself.

How has writing this novel changed or expanded your perspective as a migraine sufferer?

I’m gentler with myself about it. I try so hard to be perfect—no aspartame, very little booze, super hydrated. The amount of vigilance you need—I just can’t be that vigilant. Nobody can be, and it’s no way to live. I think it extends to my writing life. Do what you can do. Write as fast as you can. Claim your time. Claim your words. Claim your work. That doesn’t mean don’t collaborate, but you have to claim your experience, pain and all.

And pain can yield pleasure. Sometimes we have to say, “I want to have two glasses of champagne at this wedding. I know this might trigger a migraine, but I want to experience this pleasure and live in this moment.”

You want to dance and you want to taste things. That’s so much a part of this book. Our deprivations—when do we defy them? When do we say, “I want that champagne. I want that chocolate.” Being in the moment is too important.

This reminds of something Jack Gilbert wrote: “We must risk delight.”

That one is so good—I just love him. Delight is worth it—but we have to decide for ourselves. “What do you want to do with your one wild and precious life?” That’s over-quoted, but the sentiment is true. We want to succeed. We want to be good citizens. We want to show up for one another. But every so often, it’s just about enjoying being at that table, belly up.

You Might Also Like