American TV's king of 'radical kindness': Britain, prepare to shed a tear for Mister Rogers

Did you have any awareness of who Fred Rogers was?” Morgan Neville asks me when we meet. No! I say. “That’s what I’ve been hearing,” he chuckles. “Nobody here knows who he was. But he was the most famous children’s entertainer in the history of America.”

Neville, an Oscar-winning American documentarian, has made Rogers the subject of his new film, Won’t You Be My Neighbor?, and for British audiences the first hurdle is: who he?

Children’s television is now global: Paw Patrol and Dora the Explorer are watched by tots from Colchester to Caracas. But in the pre-internet age, even while soap operas, crime shows and sitcoms criss-crossed the Atlantic, children’s programming seldom travelled. If you try to engage an American in a conversation about George, Zippy and Bungle, Johnny Ball, Fingerbobs or Bagpuss, they will have no idea what you’re talking about.

The same applies the other way around. I asked friends of all ages if the name “Mister Rogers” meant anything to them. With the exception of a colleague who had spent four years of his childhood in the US, I drew a complete blank. Yet Fred Rogers, who died in 2003, was a figure of titanic influence on several generations of American children.

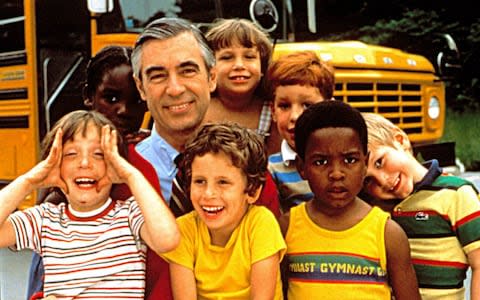

Between 1966 and 2001, he had a weekday afternoon TV programme, Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, in which he wore zip-up cardigans and sang songs and fed an aquarium full of entirely unremarkable fish and fooled around with a bunch of hand puppets. No jump-cuts, no custard pies, no stunts. Just a grown-up speaking to children in a kindly way. He did this for 912 episodes. And it made him a sort of secular saint. (Though, as an ordained Presbyterian minister, perhaps less of the secular.)

Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood – there’s no getting around it – was as square as square could be. It made (to offer a transatlantic analogy) Playschool look like Tiswas. It made Tiswas look like Mad Max: Fury Road. In one episode, they offered to give the children a sense of how long a minute was. They set an egg timer, and just sat there in silence, on air, for a whole minute. Rogers had his puppets, his section called the “Neighborhood of Make-Believe”, and his closing song about it being a good feeling to be alive. And that was about it.

Neville’s film, its title taken from a lyric of the theme tune, tells Rogers’ story from his not-always-happy childhood to his eventual enthronement as the United States’ favourite grandfather. The idea was seeded when the director found himself watching old YouTube footage of Rogers, a figure he remembered from his own childhood, giving college commencement addresses and he wondered: “Where’s this voice in our culture today? Where’s this voice advocating for civility and empathy and these kinds of things which are so rare. It was not a nostalgic instinct at all: it was how do I get this voice into 2018?”

It turned out there was an appetite for this voice – and how. Won’t You Be My Neighbor? is the highest grossing biographical documentary of all time. “It’s a shock to everybody,” says Neville. “Myself included.”

He thinks it succeeded “in part because it’s a film about something that people don’t make a lot of films about. We live in such an ironic age that even our superheroes are sarcastic. I was insecure about putting such a sincere message out there. It’s so easy to think of things like niceness and kindness as trite, quaint, out-of-date ideas.”

Early in the documentary, someone remarks that Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood was more or less a compendium of things that aren’t supposed to work in television: rickety sets, unstarry star, lots of not much happening – and yet it was a huge success. Same goes, a little, for Neville’s film.

When you consider the tormented love stories, the agony and ecstasy, the dark secrets, the sex and drugs and rock’n’roll, the tantrums and tiaras available to the biographical documentarian, when you consider the cast of possible subjects in politics, music, sport, showbiz… Isn’t it a bit weird that the thing that has really worked is a documentary consisting of archive footage and talking heads about an old geezer in knitwear who never said boo to a goose in his long life?

Won’t You Be My Neighbor? is, in a way, something revolutionary. It’s not a film that trades in the dark side of stardom. Its subject was a man who, as Neville tells me, loved dirty jokes but would never tell one himself. There’s no third act in which we plunge down some Bill Cosby or Rolf Harris or Jimmy Savile rabbit-hole to view an avuncular icon in a sinister new light. Rather, it’s a film about uncomplicated and determined kindness – what Neville calls “radical kindness” – and as you watch it you will find tears springing unbidden to your eyes.

Mister Rogers was just… a nice guy. A really nice one, with an unpushy Christian calling and an unsinister love of children, who believed that he could use television to help children navigate the emotionally turbulent territory of their early years by telling them that every single one of them was unique, and fine exactly how they were, both loved and deserving of love.

“We talk about things like emotional maturity, and slow culture, and mindfulness – things that are now very common,” says Neville. “But Fred Rogers was doing them 50 years ago when there was no name for them.”

Rogers didn’t offer escapism, though. Through one of his puppets, Daniel the tiger, an avatar of his own childhood self, he addressed feelings of fear and bewilderment, grief and rage, and told young viewers it was OK to feel these things and suggested ways of managing them.

And it was Mister Rogers who at times of crisis – from the Vietnam War and the assassination of Bobby Kennedy through to the Challenger disaster, the Aids crisis and 9/11 – helped make the news comprehensible and bearable to younger children. “He always said that the outside world keeps changing,” says Neville. “But the inside world of the child never changes.”

In his quiet way – though he was a lifelong registered Republican – Rogers championed progressive values. His 1969 testimony before a senate subcommittee (he read the lyrics to one of his songs) is credited with securing the future of government-funded children’s television. In the late Sixties, when black swimmers were being forcibly ejected from white swimming pools, Rogers did a section on his show where he invited Officer Clemmons (a gay, black pretend policeman who was a regular on the show) to join him bathing his feet in water on a hot day.

Rogers at one point quietly moved church in his hometown to one less intolerant of homosexuality. Neville identifies him with the so-called “Roosevelt Republicans” – fiscally conservative but socially tolerant – adding that “to him they were not progressive ideas but Christian ideas”. Yet on Mister Rogers’ Neigborhood he never once mentioned God, for the same reason that even as a pacifist he refused publicly to condemn the Gulf War, knowing that some children watching might have parents fighting in it: he didn’t want a single child to feel excluded.

The most controversy he ever attracted wasn’t political: it was when he did an episode trying to explain to children that Father Christmas was an adult conceit rather than a real person (he was worried that this figure who keeps a list and breaks into your house at night might be frightening to children). As Neville says, “A lot of parents weren’t very happy.”

But his bond with children was unbreakable. At one point Rogers was receiving more post than anybody else in America: and he responded to every single letter personally. “He thought that was his real work: even more than the TV show.” When in his later years he went on the New York subway, a friend reported, the entire carriage would start singing his theme song. Adult women came to him when he delivered a commencement address to thank him for being there in their childhoods.

Yet it has been suggested by some that the entitlement and rage of the modern American adult is directly linked to Fred Rogers; that he’s the father of “generation snowflake”. Did his message that you’re valuable just the way you are – that you don’t need to do or be anything special to be deserving of love – help create a population of entitled brats who expect the moon on a stick?

As one contributor to the documentary points out crisply, you can take that view – but in so doing you also have to set yourself against the whole of mainstream Christian theology, stressing as it does God’s unconditional love for His creation.

And as Neville says, “the film asks a lot of questions. It’s not a preachy film. It asks, I think, what are you going to do? What have you done? The point is that we all have to take responsibility. People ask me who the new Mister Rogers is. And the heart of the film is: there is no new Mister Rogers.”

Rogers will soon be the subject of a biopic starring - who else? - Tom Hanks, but the emotional impact of Neville's film will be hard to top. “I didn’t expect audiences to act like they did,” he says, “until that first screening in Sundance. It just blew me away. The entire audience cried. And from that first moment the audience felt like it was their film, not my film. They all felt like this is mine, you made it for me, it means something to me."

He quotes a line from his favourite US review of the documentary: “'Watching this film is like freebasing sincerity.’ I’ll take that!”

Won't You Be My Neighbor? is released in the UK on November 9