The Amazing Story Behind The Williamsburg Bray School

Colonial Williamsburg's newest historic site is an 18th-century school for free and enslaved black students.

Brendan Sostak, The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

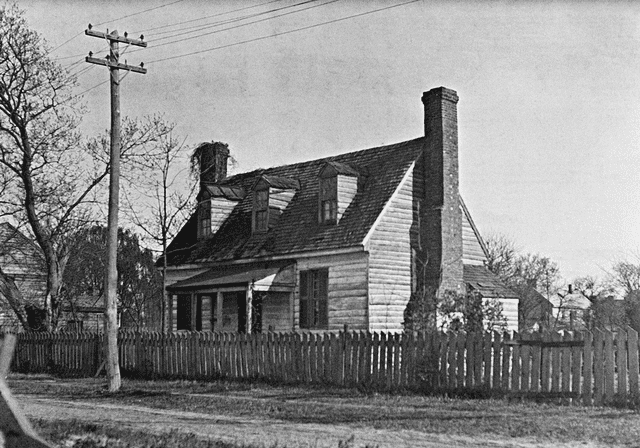

Before it found a permanent home at Colonial Williamsburg, the little white cottage on William & Mary's campus lived many lives. Known as the Bray-Digges house, it was once a residence, the university’s military science department, and an Army ROTC office. About 20 years ago, Terry L. Meyers, chancellor professor emeritus of English at the university, thought the building might date back to the 18th century, and started investigating its history. It would take decades to solve the mystery.

Special Collections, John D. Rockefeller Jr. Library, The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Related: The South's Best 2024

What Was The Mysterious House?

To determine the age of the cottage and its original purpose, the university partnered with experts from Colonial Williamsburg, "the world's largest living history museum" and a 2024 winner in our annual South's Best Awards. Because it had been altered over the years, it was difficult to pinpoint when it was originally made. Researchers painstakingly studied the building’s construction and materials and tried to connect it with historical records.

In 2020, a sample of wood brought the whole story into clear view: it was the Williamsburg Bray School, one of the country’s first schools for Black children, both free and enslaved.

What Was The Williamsburg Bray School?

A London-based charity called the Associates of Dr. Bray had established several schools in the colonies to give African Americans a “religious education”. At the suggestion of Benjamin Franklin, one opened in Williamsburg. From 1760 to 1774, a white teacher named Ann Wager educated up to 400 children from ages 3 to 10 in the two-story building. Lessons focused on Christianity and reinforced slavery, but records show that Wager taught her students to read and write, and other skills like sewing. More than just a historic building, the Bray School offers a rare window into the lives of these children.

Tonia Cansler Merideth is an oral historian with the William & Mary Bray School Lab, which was created to document and preserve the school’s history and connect with descendants of the students (Merideth herself is a descendant). As Merideth has discovered, the lessons taught in the school extended far beyond the building itself. “Two of the free students, Mary and Elisha Jones, returned to their community and taught them how to read and write, becoming the first black teachers in Virginia,” she says.

Brian Newson, The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

How You Can Visit The Bray School

Last year, the cottage was transported on a flatbed truck to Colonial Williamsburg, making it the 89th original building that has been preserved. After careful restorations, it is expected to open to the public this fall. Currently, the museum is offering walking tours of key sites connected to the Bray School.

Matt Webster, the museum’s executive director of architectural preservation and research, calls the building a rare instance of survival. “Often the houses of the gentry survive, while the structures of the middle class, lower class, and enslaved are lost to make way for progress,” he explains. “The marks left behind in this building such as fingerprints in bricks, saw marks on framing, and worn floorboards and handrails return some of the humanity to individuals whose stories have been historically overlooked.”

Wayne Reynolds, The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

For more Southern Living news, make sure to sign up for our newsletter!

Read the original article on Southern Living.