Alison Bechdel on Jane Austen, ‘Detransition, Baby’, and the Book That Makes Her Feel Seen

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

“Hearst Magazines and Verizon Media may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below.”

Welcome to Shelf Life, ELLE.com’s books column, in which authors share their most memorable reads. Whether you’re on the hunt for a book to console you, move you profoundly, or make you laugh, consider a recommendation from the writers in our series, who, like you (since you’re here), love books. Perhaps one of their favorite titles will become one of yours, too.

It’s been nine years since Alison Bechdel released her last graphic memoir, Are You My Mother? and 15 since her first, Fun Home, which was adapted into a Broadway musical that won five Tony Awards. Jake Gyllenhaal will produce and star in a musical film version. Her latest, The Secret to Superhuman Strength, explores her relationship to fitness with creativity, with a book jacket featuring her doing a more graceful Archer pose than she can manage in real life. In instructional videos, she bikes, hikes, walks a slackline, and cross-country skis in the woods of Vermont, where she lives with her partner.

You may have heard of her Bechdel test, which rates movies on whether they 1) feature at least two women, who 2) talk to each other about 3) something other than a man. It was the subject of a Dykes to Watch Out For comic strip, and she has attributed it to a conversation with a friend named Liz Wallace.

Fun Home, about coming out to her parents only to discover that her father was gay, was what she and her brothers called the funeral home where her father worked (yes, Bechdel pitched in). She’s a MacArthur Fellow, attained a black belt in karate, can’t run with music, has kept a diary since she was 10, and held onto an almost-40-year-old can of water chestnuts (a sentimental housewarming gift) until she Marie Kondo’d it. It was, of course, harder to purge her books.

The book that:

…helped me through a breakup:

I read Roland Barthes’s A Lover’s Discourse in college after getting dumped by someone. It was a strange, difficult book, but when I finally got a handle on it, I felt linked to a long and noble line of unrequited lovers.

…kept me up way too late:

The Little Stranger by Sarah Waters. The weird goings-on at Hundreds Hall were so scary I kept forging on, hoping for a slight break from the tension that would enable me to put the book down, but one never came. I was a wreck for days.

…shaped my worldview:

Zami by Audre Lorde. Lorde’s examination of her multiple outsiderness helped me to understand what a great limitation it is to be on the inside.

…I swear I’ll finish one day:

I had to stop reading The Overstory by Richard Powers because it was just too painful. But I really need to face my climate grief, and I think reading these wrenching stories about people and trees is one way to do it.

…currently sits on my nightstand:

Kindred by Octavia E. Butler. I’ve never been into science fiction, but after hearing people rave about Butler for years, I’m determined to take the plunge. I might have cheated, though, by choosing the book of hers that sounded the least sci-fi-ish.

…I’d pass onto a kid:

If I had a kid, I’d give them the collection of Colette’s memoir writing, Earthly Paradise, that my father gave me when I was 19, saying, “You should learn about Paris in the 20s, that whole scene.”

…made me laugh out loud:

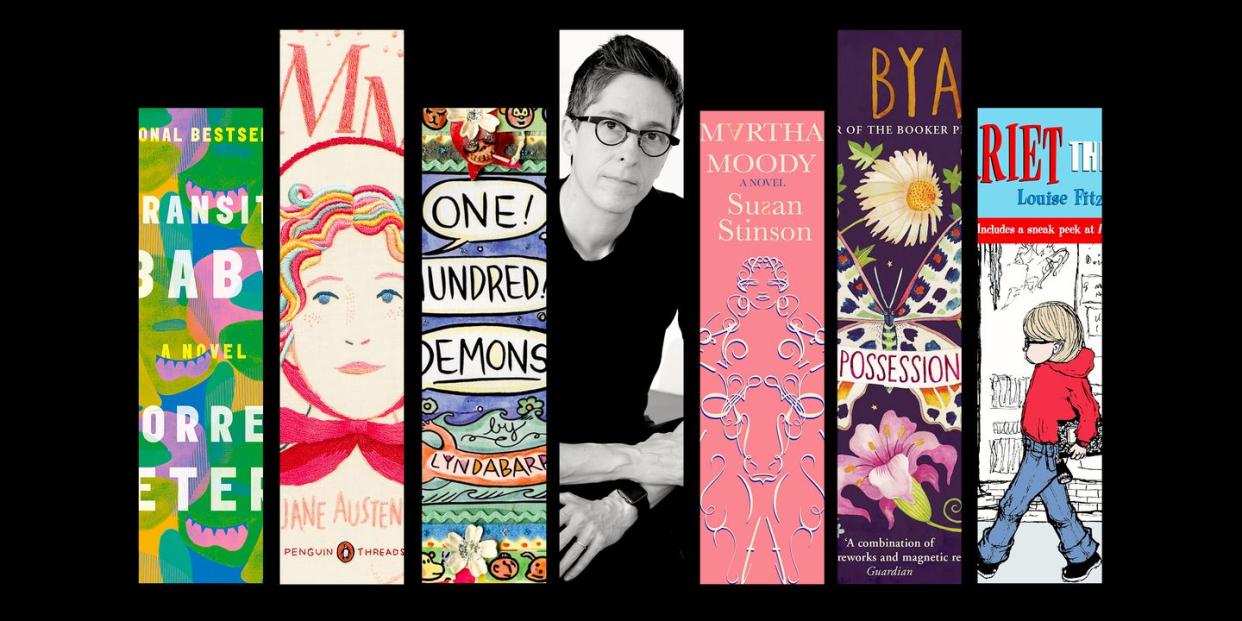

Lynda Barry’s One! Hundred! Demons! It’s a collection of autobiographical comics with lots of her usual brilliant and funny stuff about childhood, but I especially love the glimpses into her adult life. The story about head lice and her worst boyfriend is worth the price of the ticket.

…I’d like turned into a Netflix show:

Megan Marshall’s biography Margaret Fuller: A New American Life would make a kickass show. Fuller was a groundbreaking, 19th-century feminist thinker and journalist. She’s gotten short shrift in the history books, in part because she died very tragically at age 40, but in part because people found her “difficult.” This is one difficult woman well worth a miniseries.

…I last bought:

Detransition, Baby by Torrey Peters. I try to keep up with things, but I found the jacket copy so utterly bewildering—Who had detransitioned from what, whose baby was it?—that I simply had to know more. I was rewarded with an exquisite comedy of manners.

…has the best opening line:

Martha Moody by Susan Stinson. This “speculative western” first came out in 1995 but was just reissued. The first sentence is magnificent in the way it’s a microcosm of the whole book, as well as a glimpse at the way Stinson writes so beautifully about fat bodies: “I was crouched next to the creek baiting my hook with a hunk of fat when I heard a rustling on the bank upstream.”

…I’ve re-read the most:

I have Jane Austen on permanent rotation, so I won’t count her books. But next in line is Gaudy Night by Dorothy L. Sayers. It’s set in a women’s college at Oxford, and is partly a detective story, partly a love story, and partly a disquisition on the importance of intellectual integrity—a surprisingly potent mix.

…I consider literary comfort food:

Possession by A.S. Byatt. Like Gaudy Night, another campus novel—I apparently have a weakness for this genre. This one is a tour de force in which two modern-day academics are researching two 19th-century poets—Byatt goes so far as to create a whole body of work for each of the Victorians. You might not think a book categorized as “historiographic metafiction” would be a page turner, but you’d be wrong.

…makes me feel seen:

But not in a good way: The Talented Mr. Ripley by Patricia Highsmith. Like me, you are probably not a charming, sociopathic, repressed gay man who kills a guy he’s in love with then jaunts around Europe impersonating him and living off his trust fund. But Highsmith forces such an intense identification with this character that you’re rooting desperately for Tom Ripley to get away with murder.

…features the most beautiful book jacket:

All of the old (1963-1986) Penguin English Library paperbacks are paragons of graphic design, but if I must choose only one, I’ll go with Jane Austen’s Emma. Each cover features a detail from some piece of artwork that bleeds off the edges, with an elegant rule separating the author’s name from the title—set in Helvetica, of course. With a glorious signature orange spine. The 2012 redesign of the series is pretty impressive, too, but not quite as pure.

…I could only have discovered at:

On my first visit to Womanbooks in New York City in 1980, one of the many startling books I ran across was X, a Fabulous Child’s Story by Lois Gould. It was about two parents who raise their kid as part of an experiment to keep its gender unknown to everyone except them—pretty far out for the era, not the sort of thing you’d find down at the mall.

…I’d want signed by the author:

Harriet The Spy by Louise Fitzhugh.

…I asked for one Christmas as a kid:

When I was 10, I was looking at the kids’ books in the New York Times Book Review and saw a new one by Maurice Sendak, In The Night Kitchen. I put it on my Christmas list, feeling very grown up and in-the-know. When my mom asked if I wanted it because the little boy in the story was naked, I was mortified—I hadn’t read that part. But the book was under the tree.

You Might Also Like