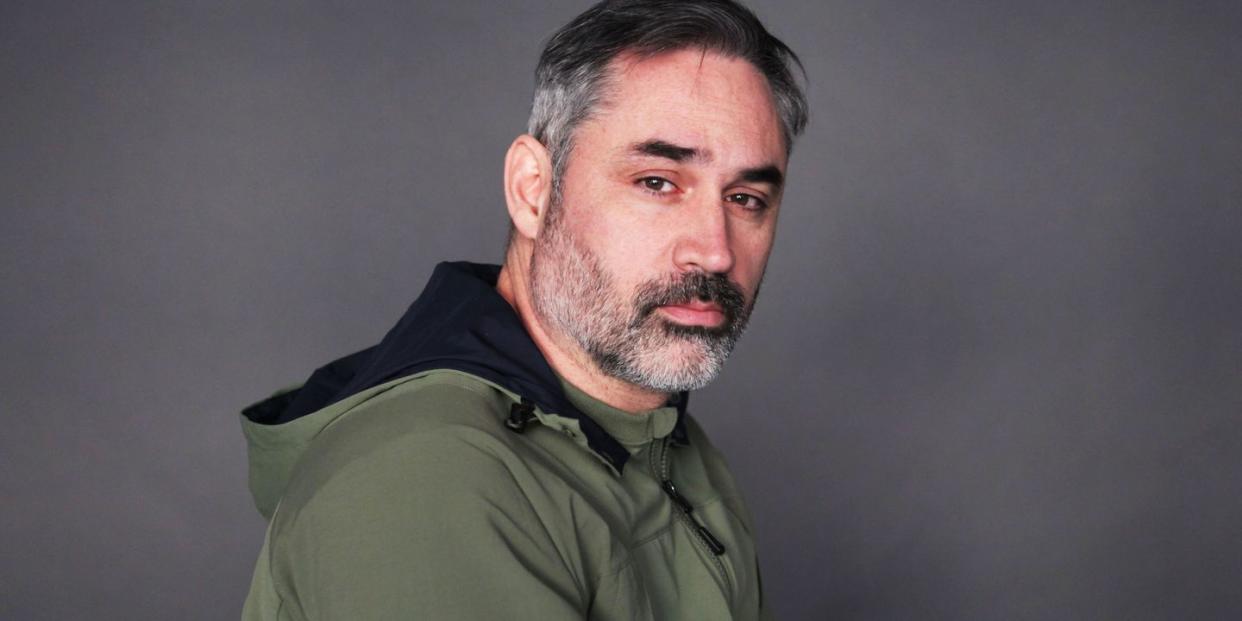

Alex Garland Says You Have No Free Will

“That is the dumbest shit I have ever heard, what a load of fucking bullshit!” The irate man was deep into an argument with writer and director Alex Garland, who doesn’t normally pick fights. When Garland had this debate before—and he’d had this debate already dozens of times, though mostly with friends—people responded reasonably. They’d hear him out. Garland himself is a reasonable enough guy, a typically-reserved, careful conversationalist who has that English habit of qualifying statements with “rather” and “sort of” and, sometimes, “rather sort of.” It would be difficult to imagine Garland losing his cool.

“Normally I'd just let it go,” he tells me months later. “But there was something about the way this guy reacted that, in truth, probably just irritated me. I was like a dog with a bone. And at that point, it sort of turned into a kind of chess match. He got angry. He got hurt. So I was like: fuck you.”

Garland, known best perhaps by his recent sci-fi hits, Ex Machina and Annihilation, had been working through a new idea with friends and acquaintances and anyone whose brain he might pick. It was all shaping into a screenplay, Devs, an 8-part TV series about a team of mock Silicon-Valley programmers who creates a machine which, using quantum physics, can determine every event that has and will ever happen. How? Because the universe, according to Devs, is deterministic. Or as Garland puts it: “Things don’t happen in magical ways; chairs don’t suddenly pop into existence.”

“I was just trying to figure out in my own head or in conversations with friends where—if free will exists—does it reside?” explains the director. “And it just became harder and harder to find.”

The suggestion also made some listeners more and more incensed. What seemed obvious to Garland, others found offensive. Or rather: fucking bullshit! That’s because determinism implies we never actually make “choices.” We are not free, but necessitated, impotent.

Which brings Garland to the irate man.

“He goes, 'How could you even say something as dumb as that?'” remembers Garland. “And then I'm like, 'well, here’s how.'”

Garland grew up in London. His father was a cartoonist. His mother a psychologist. Religion, Garland says, he absorbed by “osmosis” at school, where he would sing hymns to start each school day. In a sense, Devs began there.

When Garland was fifteen, his physics teacher gave a speech about the dangers of trick-or-treating, exclaiming, “whatever you do, kids, you should not go out Halloween-ing, because that's when the devil will enter you,” Garland recalls. “I just remember sitting there thinking, this is insane.” The event would mark a series of religious doubts, culminating in Garland’s late teens when his girlfriend became ill. She worried God was punishing her for dating Garland, a non-Jew. “So God's going to intervene in who you date, but it's not going to get involved in the Holocaust?” Garland thought. “That doesn't seem right.” Garland chose apostasy. And after college, he escaped by traveling.

Garland went to live in the Philippines where he began writing a novel. The Beach was based on Garland's experience backpacking through Asia. It was ironic Kerouac, a snide tale of late adolescents using southeast Asia as a playground of self-discovery. The novel became such a sensation that Garland, then 26, was offered a publisher’s contract for two more. He was even given a sizable fee advance. But Garland didn’t want it. He didn’t care. He was interested in film and had already started writing a screenplay, a zombie movie, 28 Days Later.

Garland then wrote more. Sunshine. Never Let Me Go. The ultra-violent cult-hit, Dredd. Then, he made his directorial debut in 2014 with Ex Machina. His screenplay, about a programmer who performs an increasingly-trying Turing test on an AI machine, Ava, earned Garland an Oscar nomination and a devoted fanbase.

Garland says all his films begin with an obsession, some concept that ruminates inside his head, which then takes him to the library—then out to discuss with friends.

“For me [Devs] began with the realization that determinism would be incredibly easy to disprove,” Garland explains. “All you'd need to do is show something that was completely spontaneous.” But showing spontaneity proved challenging.

While actions like choosing a box of Cheerios feels spontaneous, it’s hard to say that this choice is uncaused. Our decision is likely influenced by many unconscious causes—our previous meal, our cravings, a health report we saw on Facebook, an ad on TV. Our intuition is that our cereal decision could be otherwise. If we simulate this event an infinite number of times, it seems we wouldn’t choose Cheerios every time. And if on just one occasion we don’t, determinism is false. But the more one thinks about it, the harder it is to imagine this one occasion. Garland’s determinism machine was born.

Devs, however, is less concerned with proving determinism than it is in showing viewers its consequences.

One of those consequences is no doubt religious.

Like the Bible, Devs opens with original sin. A programmer, Sergei, is invited to join the team working on the determinism machine. When Sergei realizes what the machine can do, he steals the code and runs. In the woods, he is confronted by Forest, the company’s CEO and Garland’s seeming stand-in for God (played poignantly by Nick Offerman). Just as in Genesis, the newly-enlightened Sergei is banished for his crime and then turned back to dust—here after being suffocated in a plastic bag and then burned, all of which Forest knew would take place. The killing highlights one of Garland’s oldest religious holdups: how an all-knowing god can punish those he knows will sin. Also: why wouldn’t he try and stop it?

In school, Garland was told it was too complicated to understand. God moves in mysterious ways. “But the response is it's not too complicated to understand,” Garland explains. “God either knows everything or he doesn’t.” Garland’s answer through Forest: He knows everything, but he can change nothing. Sergei was always going to die. Garland’s teacher was always going to make that speech. He would always break up with his girlfriend. Etc.

Garland realizes this sort of abstract storytelling can be hard on audiences. In a sense, he could have cashed in after The Beach or when Ex Machina won an Academy Award. He could have gone mainstream. But he balked both times. He wrote two more novels at his own pace and turned from laboratory AI to nightmarish acid trip with his follow-up, Annihilation. Garland jokes some viewers probably watch his films and go, “what the hell?”

The reason, Garland explains, is that his brand of cinema is “ideas-driven” and the messaging therein can, at times, be obscure. (He tells me the shoot-em-up Dredd is partly about “the way liberals kind of love fascists.”) But there’s another quality that tends to alienate viewers.

“One of the things that some people find very problematic in the stories I tell is what they feel as a kind of weird blankness,” Garland explains. Garland first encountered this himself when he was 15, reading J.G Ballard’s Empire of the Sun. “The protagonist is a kid, and he has weirdly blank responses to terrible things happening in front of him. And that was the book, more than any other book, where I thought, oh, wow, this was written for me.”

Garland calls the blankness in his works “disassociation.” It’s the feeling of hearing your own voice recorded or seeing yourself in a photo and realizing the image you had of yourself—always through mirrors—was actually distorted, wrong. Garland felt certain of his own disassociation, that his account of himself was somehow incongruent with how others saw him. “I find it weird, personally, that I try to be self-aware, but I'm just not,” he says, very seriously. “And I do things that are hiding something about my personality [to myself]. And everybody else thinks it's completely obvious.” This thought, Garland says, literally keeps him up at night.

These questions are fundamentally questions of identity, and Garland’s work, starting with The Beach, has been a series of thought experiments driving identity into crisis: zombified London, Ava, an alien that steals human DNA, code that predicts, well, everything. Garland seeks out this dissociation, because in the blankness he’s able to ask an essential question: what does it really mean for you to be YOU? (Or for Garland to be Garland?)

In Devs, that assumed answer is simply I am me because I can choose. I have control over what I do. The blankness likely comes when the characters, and the viewer, realizes they, in fact, can’t and don’t. Of course, many of Garland’s characters never doubt their freedom. Even the ones who work on the determinism machine. They never use the machine to look into their future. “That’s something I feel happens with lots of belief sets,” Garland explains. “They are deliberately not looking too hard at their own doubts. They are saying, ‘don’t question it.’”

Garland, of course, is of the opposite attitude; blankness is productive. And in the case of Devs, Garland actually thinks that giving oneself over to determinism can be liberating. If determinism is true, its consequences aren’t just those of loss—loss of choice, loss of god. What fascinates Garland about the determinism machine is that it actually offers something: knowledge. It gives the participant full self-awareness. You’d sacrifice your belief in choice, sure. But what you gain is ammunition against dissociation: you learn why you “chose” what you chose, and so, in a sense, who you really are. Garland would take this apple in a heartbeat.

The dilemma at the heart of Devs is thus not about determinism so much as it is about knowledge. Given the power to learn the secrets of creation and yourself—given access to the determinism machine—would you peek?

“It would be almost impossible to not look,” Garland says. “You'd end up feeling ashamed of yourself for not being brave enough.” In a sense, we owe it to ourselves. No bullshit.

Seeing our choices for what they are, however, doesn’t somehow diminish us. Perhaps “impotence” is the wrong word then. While Garland’s films and novels pose and then challenge features of identity, they never feel mean-spirited or reductionist. Blank or disarming as they may be, there’s a small celebration in the individual. That she can’t quite be replicated without some alien uncanniness. That deprived of choice, he still manages to feel (and even act) free. In the end, it is really we who move in mysterious ways. Mysterious, however, only to ourselves.

You Might Also Like