Alaska Native children, youth and family well-being depends on our rights to practice subsistence

Strips of dried salmon are seen on June 25, 2009. (Photo by A.R.Nanouk/U.S. Fish and WIldlife Service)

From fish camps to whaling to berry picking, subsistence is more than a means of survival; it is a cultural practice integral to Indigenous peoples’ well-being. As Indigenous Peoples, we lack a specific word for “subsistence” in our languages. However, we understand these practices to be the sacred way we live in relationship with the world, caring for it as it provides for us. This is in sharp contrast with federal law which defines subsistence narrowly, as “the customary and traditional uses by rural Alaska residents of wild, renewable resources for direct personal or family consumption as food, shelter, fuel, clothing, tools or transportation…[and] handicraft articles.” The Indigenous definition of subsistence encompasses more than mere food security; it is a practice that cultivates familial bonds, cultural resilience, and a profound sense of identity for urban and rural Alaska Natives. Alaska Federation of Natives Co-chair Ana Cungass’aq Hoffman underlined the importance of subsistence, stating, “It is the source of our nourishment physically, emotionally, culturally, and spiritually—a fundamental aspect of our existence.”

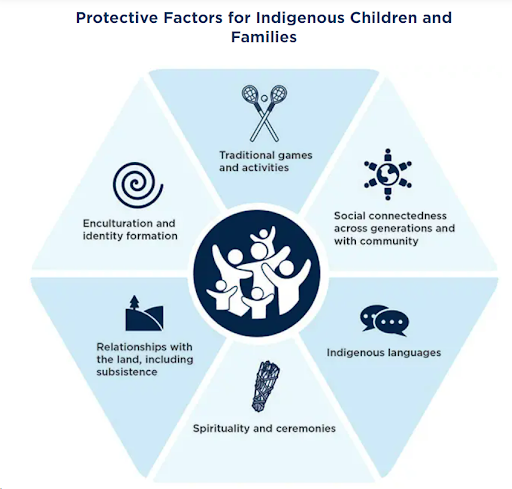

(The author created this graphic in collaboration with Krystal Figueroa, graphic designer of the Child Trends Strategic Communications team)

Understanding the critical role of subsistence in Indigenous communities is paramount— it is culture as health, acting as a protective barrier against the traumas inflicted by colonization. This trauma often manifests as mental and physical health issues, substance use, and homelessness. Subsistence acts as cultural medicine for Alaska Native children and youth, nurturing them through a connectedness framework, by: 1) teaching them their cultures and developing their identity, 2) engaging them in traditional activities, 3) nurturing their relationships with the natural world, 4) fostering social connectedness with their families and communities, 5) promoting Indigenous language learning, and 6) engaging them in spirituality and ceremony, as seen in this chart.

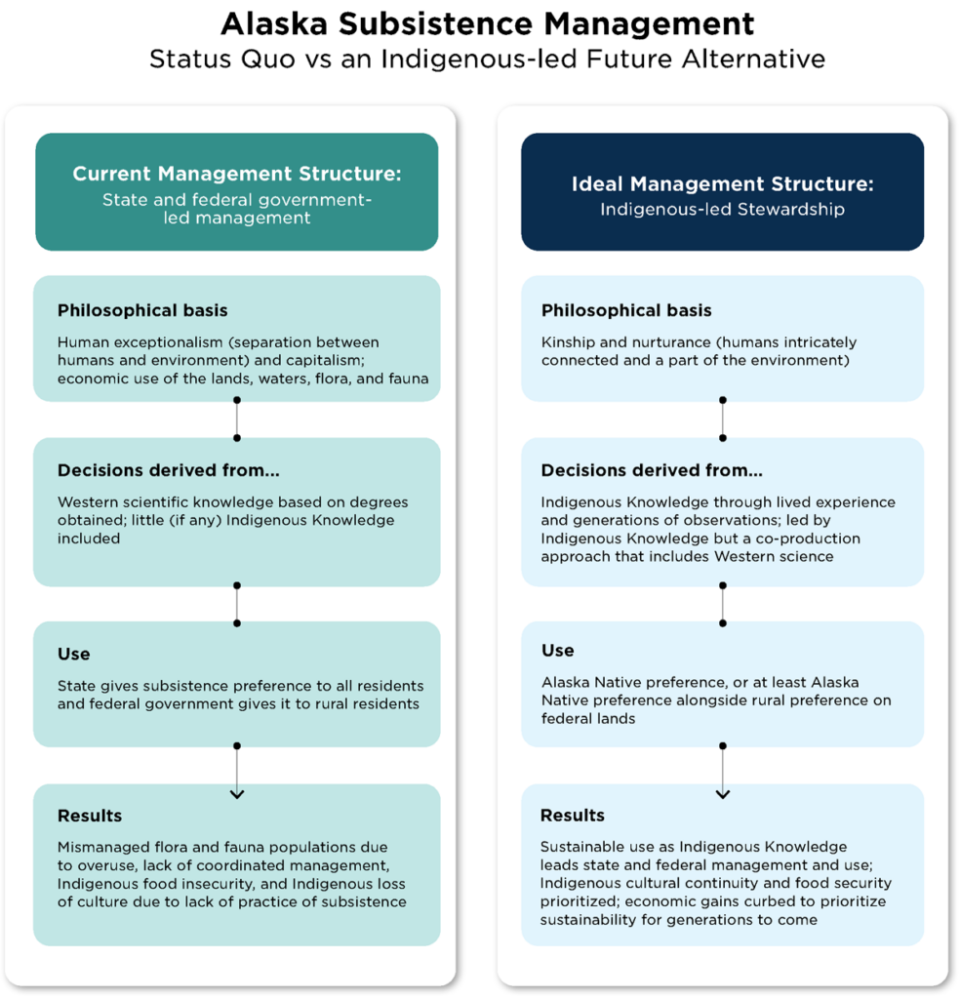

While Alaska Natives’ relationship with the environment, based on kinship and mutual care, has been sustainable since time immemorial, current land and water management in Alaska is impacting subsistence by prioritizing economic interests over sustainability. Resource extraction (whether management sets high harvesting limits for commercial fishing and trawling or allows extraction of oil, gas or minerals in areas posing high risk to the environment) is a large part of the economy in Alaska and has strong lobbies influencing decision-makers. However, this management approach, coupled with climate change, is leading to fisheries disasters that imperil not only food security for those living in rural communities but also the ability for rural and urban Alaska Natives to continue to practice our cultures and pass them on to our children. Indigenous-led approaches to land and water management, rooted in respect for the environment and connectedness, present a promising and equitable way forward that will steward the lands and waters in Alaska for all residents.

(The author created this graphic in collaboration with Catherine Nichols, senior creative manager of the Child Trends Strategic Communications team)

While extractive industry lobbyists wield considerable influence in decision-making circles, appeals from Alaska Native communities regarding their pressing issues of food insecurity, cultural loss, and the urgent need to recognize subsistence practices as vital cultural safeguards have yet to resonate with policymakers. Dr. Ralph Chami, an economist working on climate change and the loss of biodiversity, explains science often fails to sway decisions, whereas financial interests speak volumes. The hypothetical below, based on illustrative estimates, helps explain the need to value Alaska Native led management and subsistence rights.

Rural Alaska Native communities rely significantly on subsistence harvests, which constitute between 50% to 90% of their dietary intake. The loss of access to these vital sources of food would have profound consequences. A conservative estimate from 2014 suggests that replacing this subsistence food, hypothetically valued at $8 per pound — likely more — would incur a staggering cost of $274 million, when adjusted for 2024 values, this amounts to approximately $360 million annually for all communities in Alaska relying on subsistence. However, the loss of subsistence practices goes beyond mere economic implications. It signifies a cultural loss, akin to the disappearance of a vital form of medicine. This loss has the potential to give rise to profound social and health challenges, including trauma responses, within affected communities.

To safeguard Indigenous health and well-being and the state’s economy, it is imperative to prioritize subsistence as a cultural medicine and a comprehensive way of life for all Alaska Native people.

To illustrate the costs of losing cultural protective factors and the resulting trauma, 1,300 unhoused Alaska Native individuals currently live in Anchorage, away from their home communities, families subsistence practices, and cultures, accessing support services. The annual cost per person for housing, medical care, detoxification programs, and law enforcement services amounts to around $35,000, totaling $45.5 million per year for the 1,300 people in Anchorage. Without the cultural connection to subsistence practices, the cost of support services would be even greater in remote areas, exacerbating the strain on state resources. The latest census estimates show approximately 148,000 Alaska Native people in Alaska. For a conservative, hypothetical estimate based on the Anchorage rates, if even one quarter lost access to their traditional subsistence practices, lifeways and cultures, the cost of services for the resulting trauma could amount to $1.295 billion per year. In 2023, the total state revenue amounted to $15.5 billion. This is a cost the state economy cannot bear, as state legislators are already struggling with existing state revenue and expense gaps even with $3.5 billion of federal support

To safeguard Indigenous health and well-being and the state’s economy, it is imperative to prioritize subsistence as a cultural medicine and a comprehensive way of life for all Alaska Native people. Embracing an Indigenous-led approach to land and water management offers a pathway to sustainable coexistence for all. As all Alaskans, we need to come together so that we have a sustainable future; short-term profits are not worth the long term damages. Understanding the intricate link between sustainable land and water management, subsistence as food security and medicine, Alaska Native health, and the associated saved costs for cities and states is crucial for the well-being of Alaska Native people, preservation of our cultures, biodiversity and sustainable management for all in Alaska.

GET THE MORNING HEADLINES DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX

The post Alaska Native children, youth and family well-being depends on our rights to practice subsistence appeared first on Alaska Beacon.