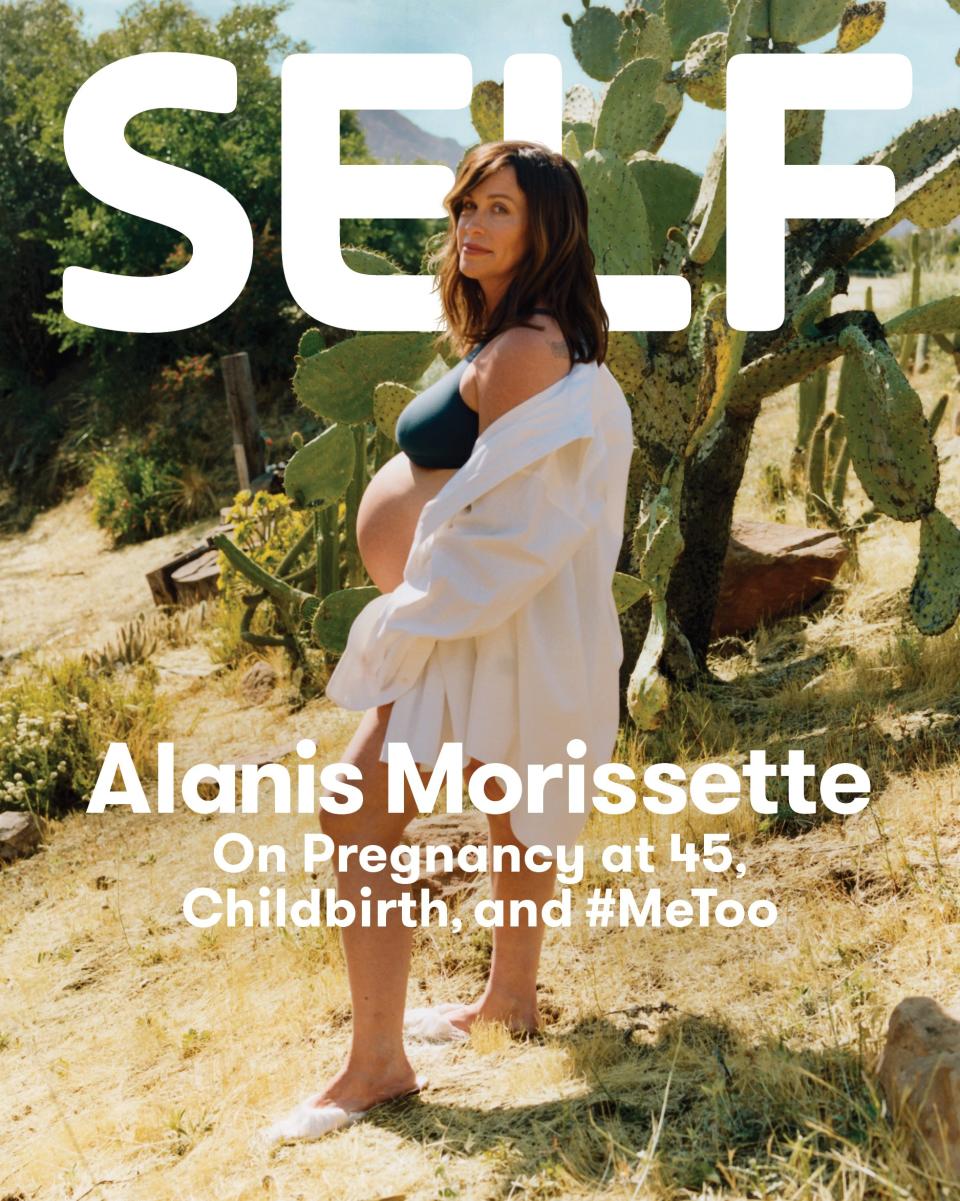

Alanis Morissette on Pregnancy at 45, Childbirth, Postpartum Depression, and #MeToo

I met with Alanis Morissette on Thursday, May 23rd, 2019, in a beautiful villa she periodically rents for meetings. (A man showed up part way through our interview, believing he was entitled to the space at the current time, and I got to see Alanis smoothly disabuse him of that notion.)

I was early, as I always am, and I was grateful for the opportunity to have 10 minutes or so to just breathe deeply and down a bottle of water. When SELF offered me the opportunity to profile Alanis, I screamed into the phone. The prospect of meeting and interviewing Alanis Morissette—the Alanis Morissette—was overwhelming to me. I wanted to do something physical to prepare myself for Alanis, like a sacrifice, so I stopped eating sugar for the month and a half between that call and our interview. This was not something I told Alanis, or even considered telling Alanis, but it seemed like the right thing to do.

I wanted something from her, I told my friends. I wanted her to look at the color of my tongue and hand me an oil or a tincture, or to touch my forehead and call me blessed. She did ask to hold my hands so she could examine my rings, and that was enough; there will be days in my life when that will propel me through preparing my taxes, or fixing my toilet. I knew that there was no chance of me being an objective journalist in our time together. I knew that I would have protected her with my body if the aforementioned man had pushed his way into the room. I knew I would tell her I too had left Canada at the age of 19, that Jagged Little Pill was my first cassette tape, and that I had three children, while she sat there beatifically gestating her own third. The question was: Would this word-vomit emerge from me the minute she sat down, or would it ooze out at odd moments? (The first, mainly.)

She accepted these offerings with grace. Alanis does everything with grace. When later in the interview she had to get up to pee, being extremely pregnant, she said so with grace. Alanis can say “I’m so sorry, I REALLY have to pee” like another person would say, “The white smoke indicates that a new pontiff has been elected by the cardinals.”

Alanis is deliberate in her movements and careful with her words, and she locks onto her conversation partner. I talked too much, which I had expected going in, but blessedly we did click, thanks to having some things in common: We’re both self-professed over-communicators, a little bit woo-y, and very emotional. And we’re both big fans of talking about childbirth, as you’ll learn in a moment.

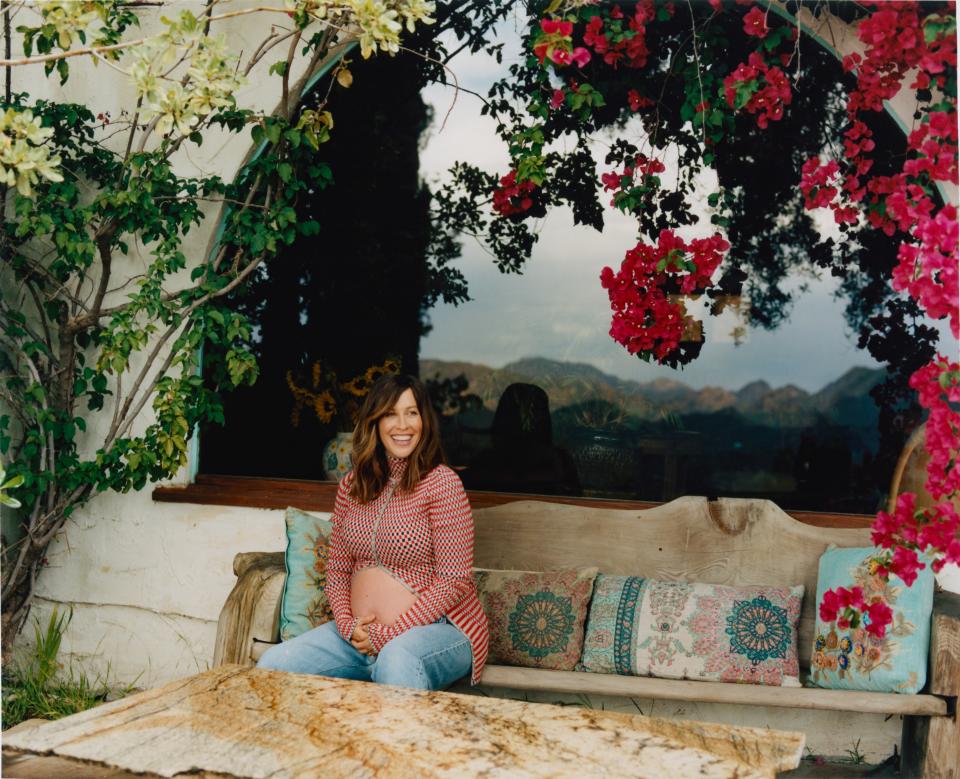

This is the point in the profile in which a heterosexual man would devote two paragraphs to describing the female celebrity’s physical appearance. I will tell you this: She was a glowing angel, ripe with new life. “Ripe” is a cliché, but Alanis could have materialized a perfectly ripe pear in her hand and gently tossed it to me. She was wearing no makeup. That’s all you need to know.

Let’s talk about the story of Alanis Morissette. To Canadians, she’s “Alanis,” and always will be. Alanis was born in 1974 in Ottawa, our nation’s windy and generally unpleasant capital (hate-mail me as much as you want, it’s terrible there). She started working at the age of 10, as an ensemble member of the very strange and very wonderful You Can’t Do That On Television, where as part of her job she would be doused with slime. Think of it as The Mickey Mouse Club, but if Tim Burton were in charge.

Alanis recorded her first song when she was 10, and then released her solo dance-pop album, Alanis, in 1991, at 17, cowriting every track. It went platinum. In 1992 she took home the Juno, the Canadian equivalent to a Grammy award, for Most Promising Female Vocalist of the Year. She toured with Vanilla Ice. Her second album, Now Is The Time, was a commercial disappointment, but signaled that Alanis was starting to chafe a bit with her image in Canada: She was experimenting with more complicated lyrics, trying out ballads. There are many, many artists who are exceptionally famous in Canada because of being Canadian, and in part because of the CanCon regulations that require our radio and TV stations contain a certain percentage of content created by Canadians in our programming. Some of these artists never meaningfully pop in the United States (The Tragically Hip, for example) and some of them manage to cross over (Alanis). But the Alanis we had in Canada was never your Alanis Morissette. Alanis was...both Olsen twins in one body. She was our Tiffany, (and more frequently referred to as our Debbie Gibson) but much more. She was Robin Sparkles. She was a tiny dynamo with wild dark hair and a mezzo-soprano voice you couldn’t possibly overlook.

Your Alanis Morissette, the Alanis Morissette who has one hand in her pocket and would go down on you in a theater, is an American. Her American career has been wildly successful, as Jagged Little Pill (which sold 16 million copies in the United States, 33 million total) was followed up in 1998 by Supposed Former Infatuation Junkie and her performance on MTV Unplugged in 1999. Her (totally baller) album Under Rug Swept dropped in 2002, topping the Canadian charts and selling a million copies in the United States.

I won’t list all the work she’s done between then and now (in addition to several subsequent albums, you may remember her as God in the 1999 Kevin Smith movie Dogma, or as the woman who confirmed Carrie Bradshaw’s heterosexuality on Sex and the City, or for her work on Weeds), other than to say she has maintained a level of production consistent with studio stars in the era of Louis B. Mayer’s MGM. For Alanis, a lot of it stems from being a workhorse from such a young age. “I always remember working my ass off 24 hours a day and looking out and seeing the kids playing in the backyard and thinking, Well, I can't do that right now,” she said.

Alanis and her husband, Mario “Souleye” Treadway, have an eight-year-old son, Ever Imre Morissette-Treadway, and a daughter just on the cusp of turning three, Onyx Solace Morissette-Treadway.

(I deliberately and carefully waited for Alanis to mention her husband by name, not knowing whether he goes by Mario or Souleye with his loved ones. Blessedly, Alanis swiftly referenced Souleye, and that was that.)

Becoming a mother was not the easiest journey for her. “Between Ever and Onyx there were some false starts,” she said. “I always wanted to have three kids, and then I've had some challenges and some miscarriages so I just didn't think it was possible.”

According to the Mayo Clinic, 10 to 20 percent of pregnancies end in miscarriage. We as a society have only recently (so recently!) begun to be more open to discussing miscarriages and reproductive struggles in general, and so it still comes as a shock to hear someone offer you the softest part of their heart to hold in this way. In a follow-up e-mail, she expanded on her feelings about her pregnancy losses: “I [...] felt so much grief and fear. I chased and prayed for pregnancy and learned so much about my body and biochemistry and immunity and gynecology through the process. It was a torturous learning and loss-filled and persevering process.”

Being somewhat of a planner, Alanis was determined to take the reins. “I had done tentacles of investigation on everything, from hormones to physicality, every rabbit hole one could go down to chase answers,” she told me. “I have different doctors who laugh at the thickness of my files. So, for me I've tried every different version from heavily self-medicating, to formal allopathic medications, to now.”

“I'm also an over-preparer for those things,” I told her. “I always get that dreaded question, in the first meeting: Do you have a medical background?, at which point I have to be like ‘No, I just want to know.’ I want to know things, I'm curious.”

“I think there are certain archetypal creatures—sounds like you're one of them—who are really research-based and just want to be as informed as possible,” Alanis said. “I'm a systems thinker, I love leadership, I love collaboration, I love every role in a system being at the top of their game. And it used to be really uncool to be an over-communicator, and now it is a boon for people and they are so appreciative with the level of accountability and the speed with which feedback is given, or answers, or responsivity. So now what people used to shame is something that people appreciate, which is the best part of evolution I guess.”

In her follow-up e-mail, she suggested that this multipronged research- and information-based approach to understanding her body ultimately paid off: “When I [...] chased my health in a different way, from multiple angles—[including, among other things] extensive consistent blood work monitoring to trauma recovery work to multiple doctor and midwife appointments to many tests and surgeries and investigations, things shifted,” she wrote. And then after all that, thanks to a combination of luck and resources, Alanis found herself pregnant at 44, having had doubts that she would get to this point, but ready to get back on that particular merry-go-round.

Pregnancy is a big fucking deal. In a very real sense, her pregnancy at the age of 44 (now 45) is why I sat in that villa talking to her. Every single one of us on this planet is the result of a successful pregnancy, but it’s still an experience you cannot explain until you’ve been through it. Ask someone about their colonoscopy (probably do not do this) and you’ll get a clear answer. Ask someone about their pregnancy, and you’ll feel like you’re overstepping, and they’ll be hard-pressed to know where to begin, or how to communicate it.

Pregnancy can change your body, forever. I think we’re getting better as a society at acknowledging the physical nonsense: Your feet may get bigger and flatter, you may never again be able to laugh without peeing a little, you may grow way more hair and then it may fall out into your bathtub drain and through your fingers over the course of your first month after giving birth. What’s harder to talk about is the shit it can dredge out of your heart. “It's this whole chemistry of emotions,” Alanis said. “Hormones and chemicals that are just coursing through your body. It [can] be triggering, or flashbacking, or re-traumatizing.”

Some of the body changes also turn back the clock. I have a metal rod and some screws in my left leg, and during each of my pregnancies, by the second half of my second trimester, I was acutely aware of them, as though the accident had occurred the week before, and not 10 years prior. I relayed this to Alanis, and she understood. “There are so many ways pregnancy can affect you,” she said. “I was ready for the ride. My first two pregnancies have been gradually becoming more proprioceptive, more attuned to the subtleties that are going on [in my body].” Subtleties like the feeling that her sacrum is a little off, or suspecting when she may need some extra Vitamin D.

Which brought us to the topic of how her children made that transition from being inside her body to outside of it. Our obvious shared delight when I brought it up made it clear to us that we were each in the presence of a true birth-story fan, the kind of person who will sit on a park bench with a stranger and clasp hands and say things like, “Were you progressing? Did they try to up your pitocin? Did they offer to pop your bag of waters?” while listening with genuine intensity and love.

We agreed that giving birth is sublime, which is not necessarily fun or good but perhaps more along the lines of knowing that you are alive, which is a horror to some and a benefit to others.

There’s a beautiful essay by Zadie Smith that seeks to parse the difference between pleasure and joy, that (in my opinion at least) starts to give voice to the profundity of this. I obviously told Alanis she had to read it instantly, at once. “Great,” she said, nodding, and wrote it down in a little notebook with a pencil, which brought me the sort of pleasure one usually only sees when a friend is actively watching your favorite show for the first time and making sounds of delight as they do so.

Alanis, who after all is a lyricist, unsurprisingly loves anytime a person is trying to articulate the ineffable: “It's so fun trying to name the nameless like this impossible task, and it's so fun to chase it,” she said.

She gave birth to her first two children at home. For Ever’s entrance into the world, she says the birth lasted 36 hours in total, with 12 hours of intensity. I nodded knowingly, having personally followed up 24 hours of labor with three and a half hours of pushing (which is...too much pushing). The intensity.

“Oh, yeah, when you’re fully in the shit,” I said.

“Yeah, sometimes literally,” she said.

“People tell you that but you don’t really believe it until it’s happening to you,” I said.

“And you don’t care,” she said.

“Not even the tiniest bit.”

It was both completely weird and yet utterly normal to be discussing profusely and carelessly defecating all over a birthing bed with Alanis Morissette.

Onyx was late, Alanis said, so she did the Castor Oil Thing, which is an unproven and somewhat last-ditch method used to induce labor that may or may not result in success. For those of you not familiar with the Castor Oil Thing, you chug castor oil, a thick and gross substance, usually mixed with orange juice.

Essentially you may shit everything out of your body, and sometimes the baby comes along for the ride (it does increase the risk of your baby aspirating meconium, among other concerns, so, you know, consult your physician first.). “It’s a very interesting little 24 hours that you can't get back,” Alanis said. Although she would not necessarily recommend it to others, she believes it did the trick for her personally. Her water broke at 12:17 a.m. and Onyx was born at 1:21 a.m.

A one-hour labor sounds like a dream, especially to anyone who knows how wildly painful the usually long process can be, but the reality is that a shorter labor may mean that you don’t get the relative luxury of easing your way into those rapid-fire final contractions. At the beginning of the average labor, you may have six, eight, 10 or so minutes to prepare for a short-ish amount of agony (think 10 or 20 seconds) before the whole cycle starts again. By the end, right when it’s time to start pushing, you might only have 30 seconds (or less!) of relief between minute-long (or longer!) contractions. That’s when (in my experience) you can lose your ability to stay on top of the pain and your ability to handle it psychologically.

In Alanis’s case, she said she couldn’t do so with either birth, and as her midwife and doula advised her to “get on top of the wave!” Alanis said she was literally begging, “HOW DO I? How the fuck do I do it?”

YOU get on the wave, I silently yelled at her midwife and doula! Be more useful! Alanis is in pain and confusion!

“When you had Onyx,” I asked, “was Ever present? Because people make very different choices around that with home birth.”

“No,” Alanis said, “He’s a highly sensitive person. [...] It wouldn't be okay with him no matter how much I prepared him. He's such an empath too, and I'm an empath with him so…”

“You can't be managing his emotions, you can't do anything except the work,” I said.

“Exactly,” Alanis said.

Alanis said Onyx’s birth was a blur, but the worst kind of blur, in that Alanis, herself, the person giving birth, could not blur out or disassociate, she had to be actively moving to help with the pain, and then pushing. “The irretrievably Canadian part of me,” she said, thought she was going to be silent during the process (“How the fuck do I do it???” notwithstanding), but to this, Onyx said, “Ha!”

Pushing solo had never been the plan. But then her midwife was delayed, and Alanis had to simultaneously manage her husband and also help him manage her.

“When I had a millisecond of reprieve, I would have to blurt, ‘Open the door!’ or ‘You’ve got to open the door between these next two contractions because they’re going to be coming, and the door’s locked and we’re going to probably be busy,’” she said. Logistics had to be accomplished, the wave had to be ignored, and Souleye still had to go unlock the damn door so the midwife could join them.

And yet, while things got increasingly scary, Alanis felt like she somehow weirdly, beautifully, became her own doula.

“I felt I was the coach,” she said. She spoke to herself like a coach would, reassuring words like "she's coming, you don't have to manipulate anything, the next contraction she's coming out, I guarantee it.”

And then, when all else failed and the terror took over, Souleye was able to get on the phone with the midwife and repeat her words to Alanis. "Hearing his voice was so beautiful," she says, “hearing him say okay, breathe in.” And then there was Onyx.

(Mutual tears. Birth.)

Alanis has previously been open about her experiences with postpartum depression, but I wanted to really get at not just the two bouts she had already fought, but also her plan for tackling it when she gives birth again in a few months.

“Not singularly relying on myself to diagnose myself is key,” she said. “Because the first time around I waited.”

And she did. She waited a long time. She waited because her entire life had prepared her to muscle through and remain superhigh functioning while grappling with a new kind of depression that wasn’t the on-and-off depression she’s been processing much of her life.

I’ve had friends for whom their postpartum illness manifested as anxiety, as a failure to bond, as an inability to allow anyone else to bond with the baby, and more rarely, the desire to harm the baby. Too many people associate PPD uniquely with the latter and dismiss the other manifestations of the illness, allowing it to dig in deeper.

For Alanis, it manifested as a familiar heaviness. “For me I would just wake up and feel like I was covered in tar and it wasn't the first time I'd experienced depression so I just thought Oh, well, this feels familiar, I'm depressed, I think,” she said. “And then simultaneously, my personal history of depression where it was so normalized for me to be in the quicksand, as I call it, or in the tar. It does feel like tar, like everything feels heavy.”

In an instance of truly disastrous timing, Alanis was starting to tour while still in the grips of her struggles post-Ever, which she thought would help snap her out of it, but of course did no such thing. “Often what had pulled me out of my depression pre-family was service,” she said. Service, for Alanis, is performing and feeling connection with her audience (when we later e-mailed her to clarify, she said, “Service for me has been through my songs…offering comfort, empathy, validation, support, information, assurance [...] with an eye toward healing and a return to wholeness”). “So I would just think, Oh I'm just going to go out into the world and serve and then I'm going to feel better, but that didn't do it. And then I had my various forms of self-medicating [that also didn’t help]. So, creativity’s not doing it, tequila's not doing it...and I even sang about it.” During this time a staple of singing through it was “Would not Come,” the lyrics of which (“If I keep my mouth shut the boat will not have to be rocked / If I am vulnerable I will be trampled upon”) symbolically scream I’m in crisis! But don’t ask me about it.

Alanis muscled through for a year and four months that first time, before reaching out to a doctor and asking “if I stick this out, will it get better?” Hearing “no, honey, the opposite” was enough to unlock her.

“The second time, though, you still waited,” I said. “How long?”

“Four months. I know!” Alanis said. “And now this time I'm going to wait four minutes. I have said to my friends, I want you to not necessarily go by the words I'm saying and as best as I can, I'll try to be honest, but I can't personally rely on the degree of honesty if I reference the last two experiences. I snowed a lot of them as I was snowing myself [the last two times].” This time, she’s lined up seven people to watch and wait and push through her demurrals and distractions, including her physician and midwife.

As you are no doubt aware, what (in a best case scenario) happens after bearing a child is signing a few pieces of paper, and then being left with a brand-new human being, with far less guidance than had you just picked up a mutt at the Humane Society. And if you felt yourself pushed back into the past, or triggered or renewed by the process of pregnancy, parenting a child makes all of that look like a picnic in the park with strawberries and cream. Either you are filled with a sudden appreciation for the ways in which your parents did their best with the resources they had, or you’re filled with a sense of shock that someone who loved you as much as you love your baby could have screwed it up so badly. Sometimes a little of both.

Then sometimes you add a second or a third child into the mix, and whatever you’ve told yourself about your parenting turns out to be nonsense. Your first child is a great sleeper not because you were a Good Mom, but because your first child was just a good sleeper. Your first two children get along well not because you set them up for success; they just like each other, and if you bring in a third, the whole system may fall apart. Your new career as an unpaid litigator who also needs to remember dentist appointments is not without its stressors.

Somewhat surprisingly, Alanis took to the challenge of raising two children with both joy and familiarity.

“Yes, there's constant negotiation,” Alanis said. “I live for collaboration and negotiation. Our whole philosophy is win-win or there's no deal. Or it's win-win or we're not done. Souleye, Onyx, Ever, and I—all four of us win. And that takes a minute.”

She said this, and I believe it because she said it, but I also do not believe it is possible in my life—maybe it is in yours? Keep the faith. Maybe we can all win. That doesn’t have to mean becoming a person who thrives on negotiation and conflict, but it’s so easy to focus on the one child who is right now in this moment causing or experiencing a problem. Alanis spoke of her family as a four-person unit, any conflict resolution requiring full buy-in. She said it can take seven minutes to accomplish, but I’ve certainly waited seven minutes just for a toddler to stop crying and explain he’s upset because he knocked over his milk.

There’s also the added layer of being a parent after having experienced some amount of trauma in your life. Trauma, handled or unhandled, or in the process of being handled, is a thread you can trace through my entire conversation with Alanis, and we touched on how it informs her parenting when she casually mentioned her “four boundaries,” which I needed to know more about immediately.

“I talk about this with my kids a lot, the four boundaries being: You can't tell me what I'm thinking, you can't tell me what I'm feeling, you can't fucking touch my body/you can't do anything with my body, and don't touch my stuff,” Alanis told me.

“Holy shit,” I said. I mean, what else is there? I found myself imagining if I could, or should, incorporate that into my own parenting, or whether I should have spent more time developing an ethos of parenting in the first place, instead of just trying to solve problems as new ones constantly roll down the conveyor belt, like Lucy and Ethel at the chocolate factory.

“And those are the main ones,” Alanis said. “Literally if ever there's a little moment between Onyx and Ever I'll just go ‘which of the four was it?’ You can't slap her, you can't grab his things.”

Alanis also said that she tries to parent her children with their empathy and sensitivity front of mind. “It’s a lot of oh sweetheart, yes your heart is broken for that person and that person's going to be okay,” she said. “And I’m so grateful for those moments because I get to notice and I get to support my children in a way that sometimes I wasn't, just because I was in a different generation. Those weren't conversations being had 44 years ago.”

What I really wanted to ask, what I want to ask every parent I know, is about the transition from being not-a-parent to being a parent. For ages after my eldest was born, I could say “I have a daughter,” and mean it and own it, but it took much, much longer to think of myself as a mother, with all the baggage that comes along with the title.

Alanis said she related to this experience, to a degree. “I myself am slightly dissociated around claiming that archetypal role [of mother],” she said. “I still have moments where it feels like it’s not dawning on me that I’m a mother. But when I look at them, I just think I'm so responsible for you.”

The pace of motherhood, which obviously varies tremendously in those early months, isn’t easy but it is...simple. Feed, clean, hold. And that can hit you hard, it can make you feel incredibly inadequate about all the things you’re not accomplishing (showering, laundry, not eating over the sink, etc.) “The days are long and the months are short,” as older parents love to tell you, translates in your day-to-day life as a sometimes blissful, sometimes agonizing slowdown of whatever your life looked like before.

“Oh, it does slow you down—chemically, circumstantially, financially, in your marriage, in your career,” Alanis agreed, reflecting on her own experiences with caring for newborns. “I think a lot of women who had one way of life, myself included, and [having a baby created] a complete sea change overnight.”

A common thing people look forward to—staring at their rather blobby, useless babies—is the day when they will begin to be able to teach them about the world, the lessons we’ve learned, the knowledge to impart. Not just the classics: “Why is the sky blue? Where does bacon come from?” but “Where was I before I was here? And “Will you be with me forever?”

We imagine too that these deep conversations will take place at the correct time and place, instead of the reality: You’re unloading the dishwasher, the cat has just puked on the carpet, you’re trying to get the baby into a car seat. In an ideal world, in a dream world, you would have the ability to carve out for each child an opportunity to feel so safe and present with you, and free of all other activities, and let that space become an organic home for the Big Stuff (obviously much easier for affluent, white parents to achieve, as is so much of what we talked about.)

For Ever and Alanis, the connection that makes space for the big questions is being outside together. “The other day he said, ‘Mom, can we go for a three-hour walk?’” Alanis said. “So we were two hours in and he asked how long we had been walking and talking. And when I said it had been two hours, he said, ‘Okay, so we have another hour.’ I can't even believe it. It's my dream.”

And thus, we come to Souleye, who as a partner has helped build a life with Alanis in which such a dream can be realized. “He's an incredibly modern man, so he has never had an issue with being married to an alpha woman, God bless him,” Alanis said. “His mom held down two full-time jobs, his dad stayed home. So there's nothing unfamiliar about [our situation for him].”

What he does focus on, and what Alanis focuses on, is the concept of provisioning. “Provisioning,” a word I had never before heard in my life before our conversation, is simply a variation on what it means to provide, in a way designed to strip our ideas of how fathers are conditioned to provide for their families, which usually means financially. What does your partner need that isn’t money? Can you read your partner well enough to know what you need to provide for them before they have to ask for it?

“In our situation, the currency of provision just looks different,” Alanis said. Souleye’s method of provisioning changes by the day, by the hour. “It might look like: Actually, just, if you don't mind, I'm going to verbally ventilate for three hours, that's a huge provision. He's with the kids right now, that's a huge provision. Especially around pregnancy, if I need something at any given time, if at 4 p.m. I need probiotics he's like ‘I'll be right back.’ So that's amazing.”

It’s so damn healthy, I thought, for a heterosexual man to be able to move past the stereotype of who should be the breadwinner and into “how can I provide what my partner needs?,” and I said as much to Alanis. Which, of course, led us to the question of Modern Society.

Alanis, still fresh off praising Souleye, made the closest thing to a frown I had yet seen from her and said, “It's one thing to say there's paternity leave for men, but the statistics are such that men are still not contributing on an admin level. And so we're interestingly dissecting that right now, which is no small thing because it's personal but also cultural, it's existential, it's evolutionary. We have to take in history.”

(I may have yelled “YES” at this point.)

“The mental load!” I said, thinking of the mothers in my life (and myself) whose male partners may believe with all their souls that they are doing their fair share, but don’t know when their kids are due for their next well-child visit, or if it’s Wear Pajamas to School Day, or who scroll blissfully past classroom e-mails asking for parental volunteers.

“Yes,” Alanis said. “The mental and the home load and the admin load and the emotional load, and whether we need to be there at 3:10 p.m. or 3:20 p.m.”

Souleye, who by Alanis’s standards, is crushing it at the game of egalitarian parenting, also has to be aware of and process her particular needs as a “highly-sensitive person.” He’s the one who will wade into the crowd of people at the restaurant to pick up the takeout order while she waits in the car. The question for me, of course, was how to live Alanis’s life as a mom, a wife, and a public figure when she needs to reset.

“Extroverts restore, in theory, with people, and introverts restore alone—so for me, one of the biggest questions with me having two or three kids, was where is that solitude? How and where?” Alanis said. “For me, it's just about getting really creative, and maybe it's a hotel room here or bathroom stall here. Making sure there's doors that go out behind our house so there's a little area with a little gazebo here...whatever I need to do to create this. It’s not anyone else’s job to be responsible for my temperament. Maybe pin-drop silence right now is the key. Or it might be hey, being pure presence with my daughter right now is the key. Or right now crying is the key. Fucking binge-watching a TV show is key.”

(This is when I told her to watch Fleabag, and she wrote that down too.)

We do have to talk a little about the uniqueness of Alanis’s experience, here, and the pointlessness of feeling like she’s effortlessly juggling balls while we’re looking for them under the bed. Alanis is clearly a woman of means; she has a partner who has the time and flexibility to devote to filling in the gaps that she cannot. There are very few people who would think a year and four months of postpartum depression sounds great, but there are millions of Americans who have to be back at work within six weeks of giving birth.

The Cut recently published an essay challenging a recent uptick in mothering memoirs by white, mostly affluent women, who have greater freedom to throw away the rules and take three-hour walks with their children without wondering who’s preparing dinner and if he can finish it before his swing shift starts. This doesn’t make anything Alanis does or says less interesting, but there are, among her many challenges, the kind of privileges that allow her to bypass a large cross-section of the problems that face the majority of American mothers: She’s not pumping in a bathroom with a broken lock, she’s not food-insecure, and she’s not raising her children without a partner, or with a partner who’s failing to pull their weight. If only we could all face our hardships within this context.

There was a question I both wanted and didn’t want to ask Alanis from the moment I got the call offering me the interview. It’s about the lead single off her 2002 album “Under Rug Swept,” which is set up as a conversation between an underage Alanis and an unnamed older man with whom she believed, at the time, she was in a “relationship,” a situation as familiar to women (and many men) as the feeling of sliding into your most comfortable pair of shoes.

The man’s lines in the song, delivered by Alanis with the withering scorn they deserve, are a master class in grooming a minor:

If it weren't for your maturity none of this would have happened

If you weren't so wise beyond your years I would've been able to control myself

If it weren't for my attention you wouldn't have been successful and

If it weren't for me you would never have amounted to very much

Just make sure you don't tell on me especially to members of your family

We best keep this to ourselves and not tell any members of our inner posse

I wish I could tell the world 'cause you're such a pretty thing when you're done up properly

I might want to marry you one day if you watch that weight and keep your firm body

So I took a deep breath, and said, “When we were talking about early patterns, it occurred to me how extraordinary it is that you put out “Hands Clean” almost exactly [15] years before [the larger] #MeToo [conversation] happened.”

I was fully prepared for an “I’m done talking about this,” or a polite “no comment” and instead was bowled over by Alanis’s reaction, which was to lean in and engage.

“How lovely that you know that,” she said, and I felt a surge of relief that I hadn’t upset her, and a wave of sadness too, that her life experiences had led her to have to answer this question at all. “I was just talking about 'Hands Clean' yesterday and how some people know what that song's about and other people just don't know? Just singing along and I'm like...that's the story of rape, basically,” she said.

It’s not a surprise that people groove out to “Hands Clean” without focusing on the lyrics. Alanis stars in the video, and in stark juxtaposition to the events described, it’s...fun? The version of Alanis we’re treated to on-screen is confident, healed, healthy, above it all, knowing she holds this man’s fate in her hands, and delivered with the powerful energy that allowed many fans to think of this incident as a mild downer in her life, not the cataclysmic reality it actually represented.

“I think about that disparity too,” Alanis said. “I remember having brought that song, the juncture at the time of okay let's shoot a video for this, and a lot of people weighing in going it would be great if we did this, and this element...what about a little karaoke? And I'm laughing...”

Because it’s an opportunity to awkwardly laugh about it all, I offered.

“Right, or be charmed, or distracted,” she said. “And I'm aware [that] some people listen to music as a relationship, as a conversation, as a dialogue. And then other people listen to music as a way of escape or rest or entertainment. And I've never been opposed to either version, I myself can't listen to song lyrics and [pay attention to anything else.]”

The song, for me, had been a grenade, I told her. I remember listening to it on loop with my friend Meg while tooling around Kingston, Ontario, when I was home from college for Christmas, hitting all the Tim Hortons we could before her curfew while she smoked cigarettes and I picked at a cruller. It made me rethink all my crushes, my platonic relationships with older men who would occasionally cross the line, and the power of my sexuality, as well as its price.

“It was a grenade for you,” Alanis said, “because you were listening. [But] it wasn't a grenade for some. And the people who were addressing it at the time, they weren't being very supportive. Still now, women are sort of being supported. It—and I—were just straight-up ignored at best. Vilified and shamed and victimized and victim-attacked at worst. There were moments where around the #MeToo era where people would say, Why are people waiting so long to speak up? And I was like really? But then also I lovingly reminded a couple of them oh, but you do remember me saying something 15 years ago, right? Word for word about this and do you remember what happened during that time?”

I told Alanis we were hitting enough trauma notes today that we didn’t need to get into the stuff with her business manager unless she wanted to. For those who are unfamiliar with the case in question, Alanis’s former business manager confessed to stealing almost $5 million from her (and to having embezzled from several other clients as well.) In 2017, he was sentenced to six years in prison.

“Yes,” she said, “and that experience was just one of many, unfortunately. So for me that was just another version of the same dynamic.”

All I could think of was Alanis’s four boundaries and the through line from being a vulnerable girl in the music industry, taken advantage of by someone whose name she has still never given up (the lyric “I’ve more than honored your request for silence” makes me grind my teeth). How of all the boundaries, “you can’t tell me what I’m thinking” is actually the most hard-won realization.

Alanis said it took a long time to come to terms with what she had experienced. “I remember forever I just kept saying, But I was participating, I was…, to my therapists,” she said. What first started to snap her out of that narrative was seeing girls at the age she had been on the street, and having a moment of extreme cognitive dissonance.

“I mean, I am there now,” Alanis said, “And now that I'm a mom: Are you fucking kidding me?”

Alanis moved to the United States on the heels of her second, more lyrical, more ballad-y, more Alanis Morissette solo album. Had she consciously chosen to leave Canada, knowing that this would be it?

“Oh yes, I made [that choice],” Alanis said, as confidently as she had said anything so far. “I made it when I was 19 and I had preconceived notions placed on me in Canada with my music. I was also writing with someone at the time who would pull out the calculator and be like hey Alanis, I know you wrote the chorus for that song but I'd say that's worth .07% of the song.” The pop princess wanted to write songs that might not rhyme, and she wanted her due.

“My perception at the time, whether it was flawed or not, was that if I moved to America it would be a clean slate,” Alanis said. “And then, sure enough, that was the case and I remember saying to myself ‘I'm not going to stop until this record is exactly to the T what I want it to be.’ And that's what ‘Jagged Little Pill’ was. And a lot of people in Canada thought this can't be true, this can't be possible.”

“There was so much ‘Glen Ballard has created this thing’ in our public discourse,” I said, referring to the perception that Alanis had her album basically crafted for her by an American Svengali, the wildly talented and experienced producer she cowrote “Jagged Little Pill” with. The perception was that our pop princess had been sexualized and pushed into an alt-queen we didn’t know or recognize. We’d bought the album (and oh, boy, did Canadians buy the album), but she wasn’t ours anymore. She wasn’t “Alanis.”

Alanis—although she’s been clear that she thoroughly enjoyed collaborating with Ballard— immediately lit UP at the idea of Ballard having made her album.”The patriarchy talking!” she said, practically spitting it out.

The “Jagged Little Pill” conversation has gotten a shot in the ass recently due to a Jezebel piece by Tracy Clark-Flory about relistening to it as an adult and discovering that, for her, “what had once felt enlivening and validating now felt grating and corny.” The internet, predictably, had collectively lost their minds over the article, but it had the effect of many, many thirty- and forty-something women digging it out and pressing play, and realizing it's still one of the greatest debut albums ever made.

I began texting and calling friends (Canadians and Americans) and asking them about their “Jagged Little Pill” experiences. For some, it had precipitated necessary breakups. Others said they applied for jobs they had thought or been told were too much of a reach. It helped other people come out of the closet, others to gain the ability to move from a series of high-conflict relationships into healthy ones without assuming it was boring.

And you know what? A few of us went down on guys in theaters. All of which, of course, came out of my mouth as, “and it still fuckin’ slaps.”

“That's what we're experiencing with the musical too,” Alanis said, referring to the musical, Jagged Little Pill, inspired by her album, now coming to Broadway in November. “I'm just like how is this possible that something I wrote when I was 19, I can still stand behind it now?”

Nicole Cliffe is a parenting advice columnist for Slate, and has written for Vulture, ELLE, The Guardian, and Christianity Today. She lives in Utah with her husband and three children.

Originally Appeared on Self