Our Air Is Literally Killing Us. What Now?

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

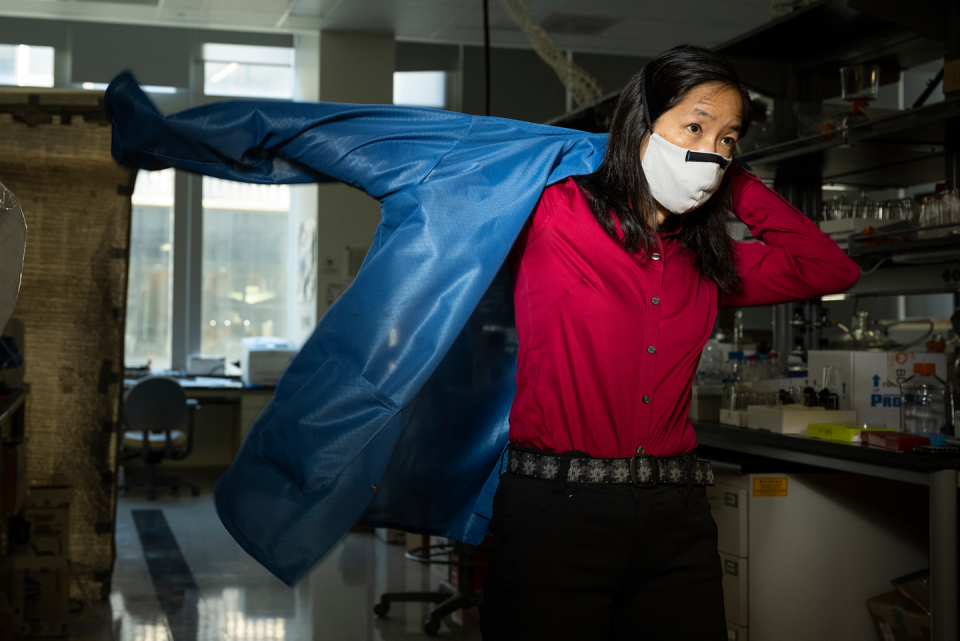

IN EARLY JUNE, as toxic wildfire smoke from Canada blanketed the Northeast, Linsey Marr, Ph.D., a professor of environmental science at Virginia Tech and one of the nation’s preeminent air experts, sat at her computer, feeling agitated as she scrolled through Twitter. She couldn’t believe what she was seeing.

She’s recounting this to me in her office in Blacksburg, Virginia, a standard academic desk-and-bookshelf setup dotted with the stuff of her life: framed diplomas and a looming print of a ski slope; a well-organized desktop hosting air-measuring gadgets and an equation-filled textbook; the black Spot bike she rode to work parked in the corner. She’s describing how, just 500 miles to the north of this very place, the scene looked apocalyptic. The next day, the air in the New York metropolitan area was so bad—the air-quality index (AQI) topped a historic 400—it turned a disturbing shade of amber. The spreading pollution tripped air-quality alerts throughout not just the Northeast but also the Midwest and Southeast. When it floated its way to her doorstep, the AQI clocked above 140, nearly at the red zone: unhealthy for everyone.

Throughout that surreal week, Marr’s thoughts swirled from the existential to the practical. The world was, of course, burning―a huge and hugely unsettling problem. And there were also more prosaic problems to consider. The mom of two (a son, 15, and a daughter, 12) needed to get her kids out the door each morning with a plan. Her son was supposed to have cross-country practice; would it be canceled? And what about her own day—could she do her usual workouts?

Petite but strong, with the ropy muscles of an endurance athlete, the 48-year-old onetime Ironman finisher relies on her morning bike commute and CrossFit sessions to stay fit and keep her mind sharp and focused all day. “It’s an addiction,” she says.

Her husband, Erich Hester, a Virginia Tech water-resources engineering researcher, feels the same way about mountain biking. On the worst air day in Blacksburg, “we were stressed,” Marr says. In her fourth-floor office in Durham Hall, on Virginia Tech’s sprawling campus, she’s surrounded by sensors that keep tabs on the indoor air. But the problems were mounting outdoors at the time, so she frequently checked the web for the air-quality data.

Marr sensed a familiar urgency gathering inside her. It was the same feeling that gripped her at the beginning of the pandemic, when she and her aerosols-science peers were raising the alarm, time and again, about Covid transmission being airborne, then getting ignored by the world’s top health officials. In those early days, she was among a handful of scientists who were adamant that public-health officials had Covid transmission all wrong. People weren’t infecting one another by coughing or sneezing within three to six feet of each other, as head honchos at the World Health Organization were saying. On the contrary, her research into pathogens and their behavior in the air made clear that tiny, aerosolized SARS-CoV-2 particles could linger for hours—and people could become infected simply by breathing. It took months of relentless advocacy for Marr and others to convince the world that three-to-six-foot social-distancing guidelines were somewhat arbitrary, not fully protective, and costing lives.

Marr helped stir a national conversation about indoor air quality. Now she’s rallying attention for outdoor air quality, too. There’s no question that bad air is bad for us: Inhaling noxious air is linked to a slew of hazardous short- and long-term health effects, increasing your risk of everything from blood clots to heart attacks to lung cancer, and emerging research seems to reveal more issues every day.

Back in June, when an editor at The New York Times emailed her to ask if she’d write something about the perils of wildfire smoke, Marr “dropped everything,” she says. Within a few hours, she’d banged out an impassioned op-ed.

Marr couldn’t have been clearer. “If the pandemic was whispering to us about air quality,” she wrote, “the wildfires are screaming to us about it.” Living in a post-Covid, climate-changing world is going to require us to adapt fast, Marr says. But can we move fast enough, and do we really know what to do? Here’s how to do more than just cover your ears to block out the screaming. You might even be able to save your life.

What Bad Air Does to Our Bodies

RESEARCHERS HAVE LONG known that breathing polluted air can kill you. A 2022 Lancet Commission found that pollution caused 9 million premature deaths in 2015. Exposure to fine-particle pollution—the kind created by gas-burning vehicles and wildfires, and also from sauteing a meal on your stovetop, accidentally burning a piece of toast, or even running your laser printer—can cause trouble throughout your body.

Fine particles (ones with diameters of 2.5 micrometers or less, known as PM2.5) and ultrafine particles (super-small PM0.1, which have diameters of 0.1 micrometers or less) have the ability to get deep inside our lungs and are thought to pose the most danger to the body. Researchers suspect that the tiniest particles may cross into the bloodstream via the lungs; those inhaled through the nose may be able to get into the brain. Once inside the body, they may contribute to inflammation and exacerbate chronic diseases such as diabetes, obesity, and heart disease. Chronic exposure has also been linked to lung cancer, cardiopulmonary disease, and, just this year, a higher risk of dementia.

If that’s not bad enough, there’s more. In the short term, you might suffer from a headache, a sore throat, dizziness, or fatigue. And particle pollution might even clog up your thinking. Scientists who recently monitored chess players in a tournament in Germany saw that the worse the air pollution, the more errors players made in their matches. Dangers are elevated for sensitive groups: the elderly, children (partly because they breathe more rapidly, Marr notes, so they take in more pollution), people who are immunocompromised, and those with cardiovascular and pulmonary diseases, as their immune systems are less able to fight off threats. Basically, our brains, our bodies, and our lives are at risk.

Marr first suspected air quality had a great effect on us when she was an undergrad at Harvard University. She’d go running on the path between the Charles River and Storrow Drive, a major thoroughfare; as cars whizzed by, she’d find herself thinking about what huffing and puffing all that exhaust was doing to her lungs. “I’d just be breathing in fumes,” she says, “wondering, Is my going running and breathing this stuff actually a net benefit or a net harm?”

Early in her career, Marr dug for answers, publishing work that sought to find out whether outdoor air pollution affected marathon finishing times. (It did—she and her team discovered a relationship between high pollution and worse marathon times for women, though not for men.)

Lest you think staying indoors will save you…it’s not so simple. As the world continues to warm (and it will keep doing so—global temperatures are projected to soar to record levels in the next five years), wildfire seasons are expected to lengthen and worsen. Even if you don’t live in an area directly threatened by wildfires, you could be affected by “smoke events” like the one that darkened N.Y.C.’s skies earlier this year.

Wildfire smoke is nasty. About 90 percent of its particles are those dangerous, fine PM2.5 ones, according to the federal government. Research hasn’t definitively shown that wildfire smoke is any more toxic than car exhaust or other fine-particle pollution (which isn’t much consolation; it’s all unhealthy). Yet an increase in respiratory-disease-related hospitalizations due to wildfire-specific PM2.5 suggests it might be. In addition, when fires overtake highly populated areas, burned structures containing plastics and other synthetic materials can emit a host of poisonous chemicals into the air. But the following strategies can help you protect yourself.

Good Moves for Bad Outdoor Air Days

SCIENTISTS ARE FURIOUSLY trying to pin down answers to the questions that swirl around when particle pollution goes up. What if you go for a hard run outside on a day when the air quality is in the unhealthy range: awful idea? Will you scar your lungs forever? It’s not clear what the long-term effects of short-term exposure to really bad air are. But it’s pretty clear that it’s not healthy, so when the AQI is high, you’ll have to make some choices about going outdoors, and especially doing a workout there.

For the best advice on what to do, Marr turns us over to Michael Koehle, M.D., Ph.D., director of the Division of Sport & Exercise Medicine at the University of British Columbia, who’s been spearheading research on the tweaks you should make. Overall, he says, “avoid exposure to air pollution as much as you can, but not so much that you become sedentary.” How to do that:

• GO SHORT AND HARD RATHER THAN LONG AND LOW. On bad air days, “avoid those long workouts, like aerobic base rides, long runs, and hikes, since the total dose of air pollution is quite high. A shorter—less than an hour—workout is better, even if you do some extra intensity,” Dr. Koehle says.

• SEPARATE YOURSELF FROM POLLUTION AS MUCH AS POSSIBLE. Check AirNow.gov for the AQI in the location where you’ll be working out. (The AQI is based on numerous pollutants, including those PM2.5 particles and how many are in the air.) Head to smaller open streets and green spaces and steer clear of major traffic arteries, large construction sites, and dense, built environments whenever you can. Choose lower-pollution times of day: That’s usually the mornings.

• REDUCE EXPOSURE ALL THE TIME, NOT JUST WHEN YOU'RE WORKING OUT. “Air pollution is bad for us 24 hours per day, during exercise and during rest, and we should do whatever we can to reduce our exposure to it 24 hours per day,” Dr. Koehle says. When a group of elite marathoners were to be exposed to high pollution for a race in 2019, he says, they were advised to do everything they could—staying indoors, wearing masks, etc.—to minimize their exposure when they weren’t working out. (Marr points out that N95 masks do a great job filtering particles of all types, large and small.) The point is to keep total exposure as low as possible.

Clearing the Indoor Air

THEORETICALLY, YOU CAN minimize contact with pollutants by taking things indoors. But indoor air can be tricky—it’s often dirtier than the air outside. The concentration of some pollutants can be two to five times higher inside versus out, according to the EPA. We pollute the air around us every day in myriad ways; cooking and laser printing can do it, but so can using grooming products and cleaning supplies, which emit harmful chemicals known as VOCs. Well-insulated modern buildings trap pollutants inside.

While you can’t check the AQI for your indoor air on the web, there are tools you can use to get pretty granular in finding out how good it is.

Marr, as you might imagine, has all the tools. She keeps four or five air-quality sensors, including a carbon-dioxide monitor, assembled on one corner of her desk. A high concentration of carbon dioxide—yes, the gas we breathe out—has been shown to negatively affect cognitive performance and productivity. As Marr and I speak, the number on the screen, a measure of the concentration of carbon dioxide in the air around us (in parts per million, or PPM), ticks up. CO2 concentration is a bit of a proxy for how well ventilated an area is. (Hers doesn’t register a concerning level during our conversation.)

She also has several devices that measure indoor particle pollution. You don’t need to be a scientist to have one; in recent weeks, I tested an indoor-air-quality monitor from PurpleAir ($199), with a handy indicator light that changes color based on the air quality. Setup was easy, and the thing worked. After I burned a piece of toast in the toaster oven (a freak but handily timed accident that actually involved flames), the monitor turned yellow, then red, detecting the particles right on cue. Marr says it’s not a must-have, but I found it useful to know what my life was doing to my home’s air. It can also help you understand more about the particle pollution in environments you don’t have control over, like at work and in the gym.

Or you can skip the monitoring step and just use these strategies to clean up your indoor air.

• OPEN THE WINDOWS... IF YOU CAN. On days when the air outside is clear, throwing the windows open helps get rid of dirty indoor air. The CDC recommends opening windows as wide as you can. I knew I’d dirtied the air in my house with my charred toast—but by opening the windows to get a cross breeze as well as powering up a portable air purifier, I was able to get the monitor to go back to green within ten minutes.

• RUN THE EXHAUST FAN WHEN YOU'RE COOKING. “Anytime you cook anything,” Marr says, “you’re generating particle pollution.” Cooking on a gas stove may make indoor air even worse than cooking on an electric one, as flames from the stove emit nitrogen dioxide and other pollutants. In May, citing that concern, New York became the first state in the country to pass legislation banning gas-stove hookups in new buildings. (In 2019, Berkeley became the first U. S. city to pass a similar ban, but it was ultimately overturned and remains in limbo. San Francisco, Seattle, and San Jose have passed or are considering similar legislation.)

• USE A PORTABLE AIR PURIFIER. When you can’t safely open windows—or even when you’re cooking or cleaning—running a portable air purifier that you can easily move from room to room isn’t a bad idea. Marr says she strategically employs two machines in her own home.

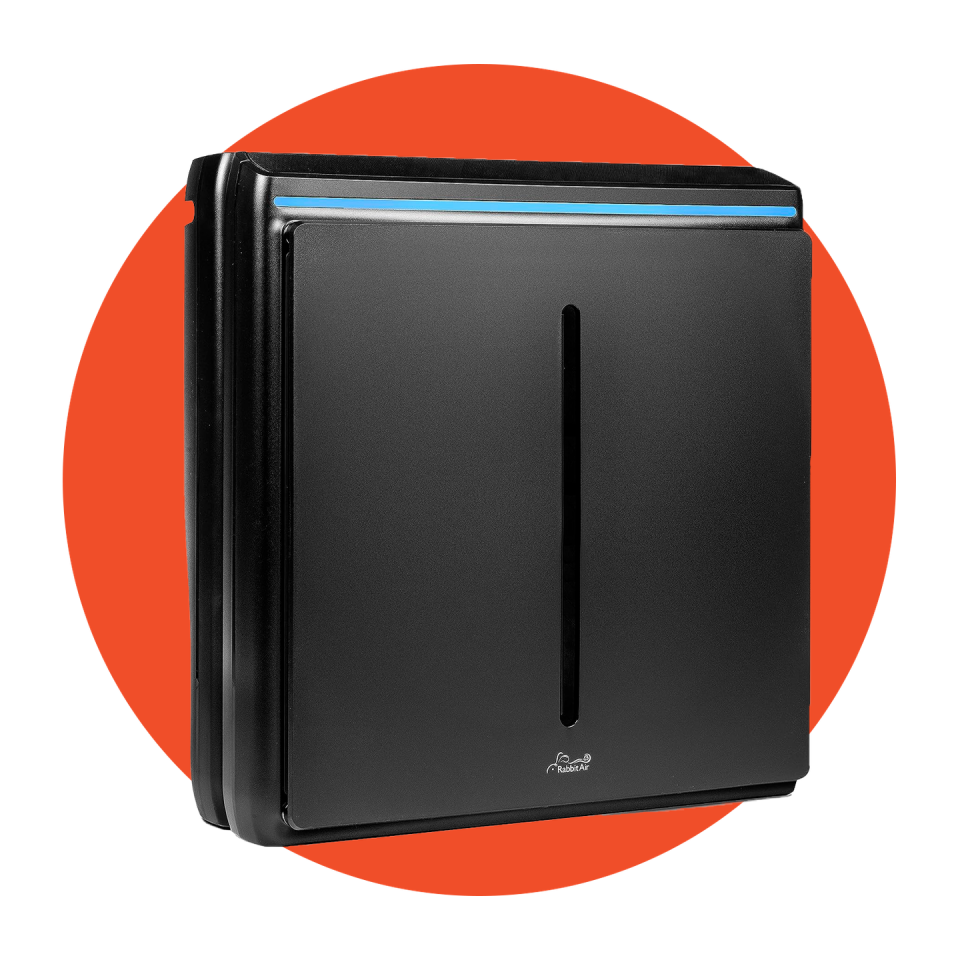

Rabbit Air A3

Rabbit Air’s latest model covers up to 1,070 square feet and can also trap particles less than 0.1 microns. Plus, it features a smart mode, which automatically adjusts its fan depending on the room’s detected air quality.

Blueair Blue Pure 311i+ Max

Loaded with a HEPA filter, Blueair’s top-tested purifier captures particles down to 0.1 microns, across 465 square feet, making this ideal for studio apartments or a living room. And it’s relatively quiet even at its fastest fan speed.

If you want to invest in one, it should have a HEPA filter. Its densely woven fibers can trap more than 99 percent of particles of 0.3 microns or larger (including virus particles and, of course, the PM2.5 particles from wildfire smoke). “People think that means they don’t work for particles smaller than 0.3 microns, but they’re even better at grabbing dangerous, tinier particles,” Marr adds, “because of the chaotic way in which those tiny particles tend to move.”

Some purifiers have indicator lights that change to orange or red to show that the air quality is deteriorating; others offer particle readouts. They’re probably not completely accurate but can give you a feel for what pollutes your home’s air (maybe setting your breakfast on fire) and what keeps it more stable.

Put the Pressure On

IN HER RECENT New York Times op-ed, Marr wrote, “We should be on the precipice of a new public-health movement to improve the air we breathe.” While our water and food are “carefully regulated for safety, there are gaps in how we ensure the safety of our air.” There are no federal standards for indoor air quality—even though, as she writes, we spend 90 percent of our time inside.

Marr has called on legislators to act. The federal government is capable of making meaningful change when it wants to, after all; the 1970 Clean Air Act, she says, is proof of that. Marr is a serious person, matter-of-fact and sometimes blunt. When we discuss the enormousness of the air-quality problem, she pauses and looks away from me briefly. “I worry about the politicization of climate change and now indoor air.” Yet what makes her optimistic, she says, is that the students she teaches are all in on fighting for cleaner air as part of their concerns about climate change. “They’re fired up. As they should be,” she adds. “Because they’re going to have to live with this for a long time.”

You Might Also Like