An Afternoon With Baseball’s Greatest Storyteller

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

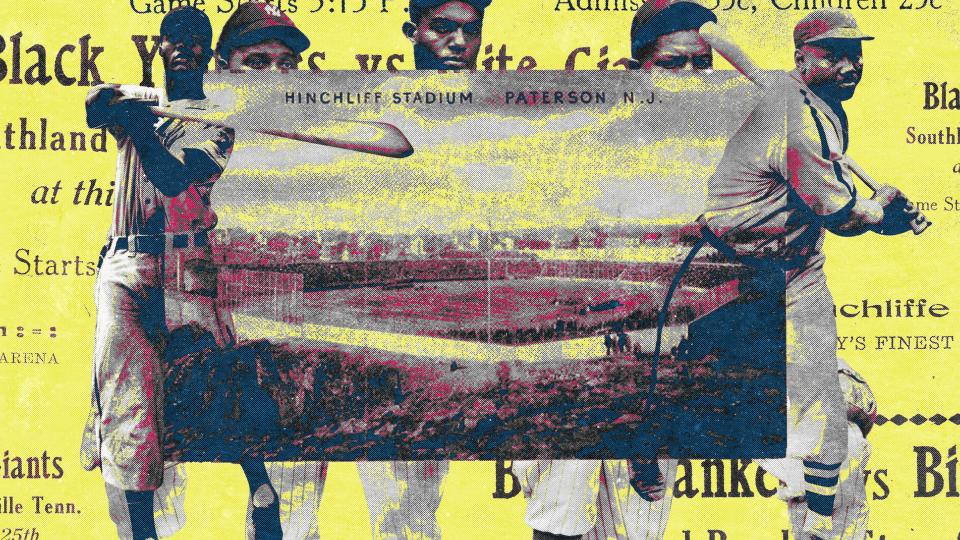

Photograph: Getty Images; Collage: Gabe Conte

When most baseball fans hear the word “museum”, they immediately think of the Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York. But some 1,200 miles west, in Kansas City, lies a different sort of baseball cathedral—one that tells a story far beyond the foul lines.

The Negro Leagues Baseball Museum (which received national designation from Congress in 2006) is the world’s only museum dedicated to Black baseball, and it’s gettting even bigger. Last May, the museum announced its plans to build a larger facility adjacent to where the Paseo YMCA—the birthplace of the Negro Leagues—once stood. Establishing an international headquarters for both Black baseball and the larger social history of this country is a true passion project for Bob Kendrick, the president of the museum. Kendrick, who’s been working with the institution for over 30 years, is known in baseball circles as the keeper of the sport’s deepest well of stories. He spoke with GQ about everything from segregation and the American spirit to video games and Ichiro.

Black history is American history, and baseball is obviously a huge part of American history. But I'm curious how you see this museum—and Negro Leagues baseball—in the larger context of the American story? And I guess, how do you try to reflect that in a museum?

Whether you are a baseball fan or not, if you are a fan of American history, you're going to love this museum. If you are a fan of the underdog overcoming adversity to go on to greatness, you're going to love this museum. Now, of course, if you're a baseball fan to boot, you’re in hog heaven.

We want everyone to walk out of this museum understanding how important the Negro Leagues were in the social advancement of this country and what they meant economically to African-American communities. The story is told on a timeline of American history, and as I describe it, everything above the timeline is baseball related. What is captured inside the timeline (and typically below the timeline) are historical reflections of things that were happening to African-Americans at that particular juncture. For our visitors, it becomes an all-encompassing history lesson. You not only come here and witness the rise and subsequent fall of the Negro Leagues, but you literally witness the simultaneous social rise of America and how this game helped our country evolve socially.

The Negro Leagues were obviously about way more than just struggle, but the struggle is a very intrinsic part of the story.

It is a fascinatingly complicated story, because what was good for social progress absolutely destroyed the Black economy. What segregation did—as horrible as segregation was—it forced ownership. You had no choice. Negro Leagues baseball became the catalyst that sparked so much economic development in so many of those urban communities. They were supporting those segregated, mandated Black-owned businesses. If you could imagine this, these athletes could ride into a town, fill up the ballpark, but not be able to get a meal from the same fans who had just cheered them, or have a place to stay. They would sleep on the bus until they could get to a place that would offer them basic services.

But what you have to admire about this story first and foremost is, they never allowed that set of social circumstances to kill their love of the game. Their spirits were such that, If I've got to sleep on the bus, and if I've got to eat my peanut butter crackers, I'm going to keep playing ball. You can't rob me of this joy of playing baseball, and I'm good at it, and I want the world to know how good I am at it. From that standpoint, it is not a woe-is-me kind of story. These athletes never cried about the social injustice. They went out and did something about it. They were never going to be angry about baseball, man, because you couldn't convince them that they weren't playing the best baseball that was being played.

The world said the best baseball was in the Major Leagues, but they never believed that. They knew how good their league was. And quite frankly, the Major Leaguers knew how good they were. They played countless exhibition games against one another. There was no doubt about their ability to play in the Major Leagues. It was just simply the social conditions of our time and maybe even more prevalent, fear, that kept them out of the game.

What is the most common thing guests tell you when they visit for the first time?

"I didn't know that." But, as my late mother would say, "You don't know what you don't know."

SiriusXM's Black Diamonds Podcast Live From Los Angeles With Dodgers Manager Dave Roberts

What surprises people most about this museum?

I think the thing that surprises most people when they visit—and this is something that we're really working diligently to help people understand—we have one of the nation's most important civil rights social justice institutions. It's just seen through the lens of baseball. But as I also remind our guests, it is triumph over adversity. So, it's a counterintuitive look at the civil rights movement, because this is not about the struggle. It's about what they did to overcome the adversity. This is one of the great American success stories.

Essentially, my success stories as a Black American have really never been tallied. No one ever talked about my success stories. The focus has been historically on the downtrodden journey of my quest toward equality. That is not my complete picture. I think it is important that you also understand my success stories right alongside those atrocities that I've had to deal with. The Negro Leagues is just that—one of those great American success stories. You won't let me play with you? I'll create a league of my own. That's the American spirit.

Right, that’s kind of the whole thing with the Negro Leagues. It’s still the American spirit, but for people who weren’t fully recognized as American at the time.

The American spirit is what really drove them, allowed them to persevere and prevail. It is really interesting, man. I do think it's the off-the-field side of the story that captivates people. Because to be quite honest, man, for me, it's a given that you're going to walk into that museum and you're going to meet some of the greatest athletes that ever put on a baseball uniform. This story has escaped the pages of American history books—very few folks know anything about this story—and they are blown away.

When you first started with the museum, what were some of your favorite things you uncovered that were previously unbeknownst to you?

Everything, because I got involved as a volunteer in 1993. Who knew that I’d go from being a volunteer to trying to lead one of this country's great cultural institutions? I consider myself to be a fan of the game. I knew the names Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson, Cool Papa Bell to some extent. But man, I had no idea about the breadth, the scope, the magnitude of what this history represented. I think all of us who are involved here at the Negro League Baseball Museum understand first and foremost that we're doing something that is bigger than we are. But if we do it right, we will leave something that will stand the test of time, and that others will get to enjoy and learn from. And that is a tremendous motivator, not just for me, but our entire team here. Thirty-one years later it's just as fascinating today as it was the day I walked into that little one-room office.

What is the significance of the museum being in Kansas City?

The Street Hotel was the Black-owned hotel right here where the museum operates now. You could walk into the sitting room of The Street Hotel on any given day, and you might see heavyweight boxing champion Joe Louis sitting in there, or the fastest man in the world, Jesse Owens. Lionel Hampton, the great orchestra leader, was a devout Kansas City Monarch fan. You might see Lena Horne. Louis Armstrong had his own semi-pro Black baseball team. They were all frequenting The Street Hotel and other Black hotels around this country.

Negro Leagues baseball brought them a built-in clientele that led those segregated Black businesses to their economic heights. When Jackie Robinson breaks the color barrier, he not only spawns integration in Major League Baseball, he triggers integration on a broader spectrum in this country. Then all of a sudden, we lose the Negro Leagues, we lose this catalyst that had been the spark for economic development, and those smaller Black-owned businesses could no longer compete with their mainstream counterparts. What was good morally and socially was devastating economically.

Do you have a favorite Negro Leagues player, or one whose story you find the most fascinating?

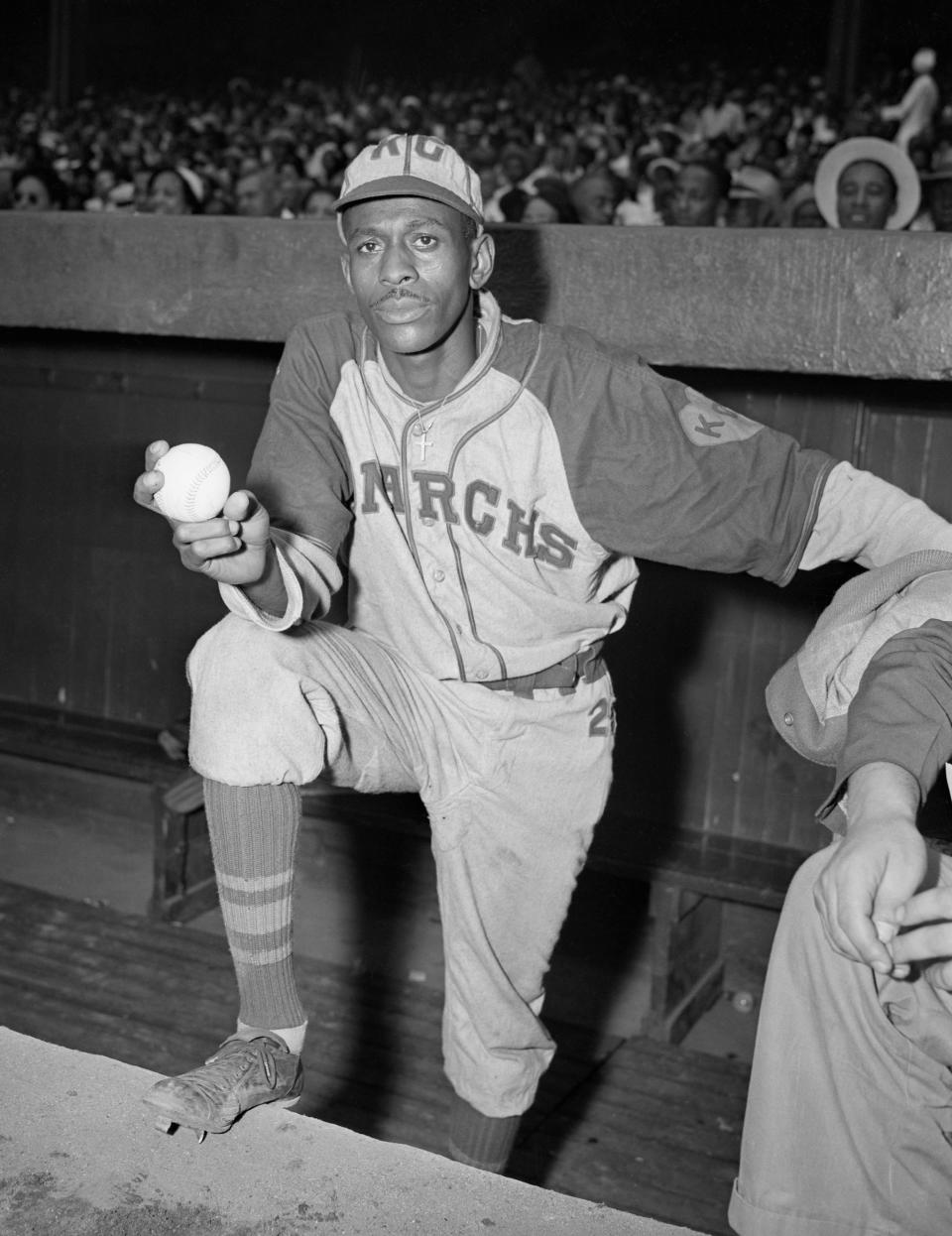

Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson. I mean, there's probably no more lore around any athlete as there is around Satchel—who of course I believe is the greatest pitcher of all time—and I think in Josh Gibson we've got the greatest combination of power and average this game has ever seen. When we look at it from a Major League Baseball standpoint, Babe Ruth, in the eyes of many, was Paul Bunyan. Josh Gibson was our John Henry. And then Satchel was, well, Satchel was just the man! Satchel had everything you needed to be one of the biggest stars in not just baseball, but across sports. He's a transcendent kind of star, because he brought a unique combination of longevity, great stuff, and charisma. He could sell it, man. Wherever Satchel went to go play, the town shut down to watch him do his thing.

Pitcher Satchel Paige Standing in Dugout

Then you had the mystique of not really knowing how old he was. It still remains an age-old mystery of just how old Satchel really was! Baseball says that he was 42 when he joined the Cleveland Indians in 1948. He was probably closer to 52 than 42. He never told his real age, and I think it's a great possibility that he didn't know his real age. We have his original tombstone here at the museum and by his birthday is a question mark. The old man literally took it with him to his grave!

How have Negro League players being added to The Show, MLB’s official video game, changed things for you and the museum?

It’s one of the biggest things that this museum has ever done, particularly as we look at ways to connect with the younger audience. Not only are they learning about the Negro Leagues, they've fallen in love with these players. It warms my heart, man. If anybody should be in a video game, it would be the players from the Negro Leagues.

As you can imagine, the kids love the swagger that Satchel has, where he has the moxie to call the outfield in, sit the infield down, and then strike out the side. I was taking some potential investors around on a tour of the museum, and I started telling my Satchel Paige story. Satchel had names for his pitches, and he had a pitch that he famously called his B-ball. I would always pose to my guests, do you know why he called it the B-ball? When I raised the question, there was a young white kid there with his father. And he looks at me, he sticks out his chest, he raises his hand, and he said, "Mr. Kendrick, I know why Satchel called it the B-ball." I said, "You do? Well, tell the folks!" He says, "Satchel called it the B-ball because he said it be’s where I want it to be." I said, "Man, you must have been playing The Show!"

One of the last remaining Negro League ballparks was nearly lost to history. But professional baseball has now returned to the fabled stadium, which stands as a monument to generations of Black players once consigned to the periphery of our national pastime.

I saw myself doing a lot of things in this life, but being in a video game is not one of them. It has made me a household name amongst a certain age group. All summer long last year we had kids coming to this museum because they saw the museum in the video game, and they wanted to meet the guy that was telling the stories. The impact of this game has been tremendous. There's this misnomer that our children don't care about history, but they do. It's just incumbent upon how history is presented to them. Any time you can be educated and entertained at the same time, that's pretty good.

One thing that I always get a huge kick out of is when I see a video of players visiting the museum. When active players come through, what do you see from them?

Oh, they are awestruck. Because if you make your living in this game, you know how difficult it is. You already know you're going to fail more times than you succeed. There's not much in this world that gets you rewarded for a 30% performance rate, but that's how difficult baseball is! The other aspect of it is, no sport holds to its history the way baseball does. It is by far the most romanticized sport of them all. We measure periods in our lives by baseball. You combine those two elements and you can see why they are in awe of these legendary athletes who played the game, as well as the way they played under the most challenging conditions. You'll never see a greater example of love of the game than you do when you walk through the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum. I think they all embrace that. It never gets old for me, man. I've been taking these athletes on tours of this museum for decades now. But again, what rings true is always that unbridled joy that they got from this game.

I would imagine a lot of them probably have the thought, This wasn't that long ago. The Negro Leagues were happening when their grandparents were alive!

Absolutely. There's a legacy there for the Black and brown athlete. If you are Black or brown, all roads lead back to the Negro Leagues, and you owe it to those athletes who sacrificed tremendously to play this game.

Well, it makes me think of someone right there in Kansas City. You can draw a direct line from the Negro Leagues to Patrick Mahomes winning three Super Bowls.

Absolutely. If he wasn't the best quarterback on the face of the planet, he might be in somebody's starting rotation now. His rookie year, I got to walk Patrick through the museum. You'll see images of him wearing Monarch jerseys and this kind of thing, because he also wants people to understand that he is a part of this legacy as well. That's what we need. We need those kinds of very visible advocates out there promoting what this museum means. I had Marshawn Lynch and Patrick Mahomes Sr. Marshawn does a pregame show for Thursday Night Football called “N Yo City.” The piece went viral. I mean, Marshawn is hilarious. But the minute he walked through the turnstiles and looked out at the field, you know the first thing he said to me? "I feel something."

That reminded me to ask you about someone who I know has been very involved in the museum for a long time, Ichiro.

I love him to death. He snuck in here the first time. That's Ichiro. No one knew. He didn't call. He just came through on his own. The only reason that we knew? He bought a bunch of jerseys and we saw the credit card slip. The very next year when the Mariners came to town, his interpreter called me and said, "Ichiro would like to meet with you." I'm like, "Ichiro wants to meet with me? Cool!"

We pull out some of the memorabilia that we have, and there's a magazine that is written in old Japanese. But he was actually able to interpret what was on the cover. He's blown away by the fact that these brothers have been to his native homeland as early as 1927. He developed, I guess you could say, a kindred relationship with [former Negro Leagues player and manager, and one of the founders of the museum] Buck O’Neil. They just hit it off.

Ichiro would later go on to say that he admired Buck's style. He was always a snappy dresser. Well, that stems from the days of the Negro Leagues! These brothers were clean, man. You would never see them outside the ballpark not immaculately dressed. As a matter of fact, if a young ballplayer came to join the Kansas City Monarchs, the first thing Buck would do was take him to see the tailor, because you had to look good!

Buck, I think he was drawn to Ichiro because he understood what Ichiro was going to go through when he came to this country. The minute he says he's coming to the U.S, what do the skeptics say? "Oh, well, you did that in your league. You won't do that in our league." Then what does he do? He put up 3,000 hits. Because a great player is a great player, it doesn't matter where he comes from.

MLB All-Star Game Red Carpet Parade

Ichiro has a pretty strong history of donations, if I’m not mistaken?

As we were sitting there talking, he reaches into his bag and he writes a personal check—a substantial gift to the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum. This is a kid from Japan who felt like this is what he needed to do. Honestly, I didn't want to cash the check. But we needed the money!

This interview has been edited and condensed

Originally Appeared on GQ