Adoring Soviet students and drunken nights with the KGB: John le Carré in Russia

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

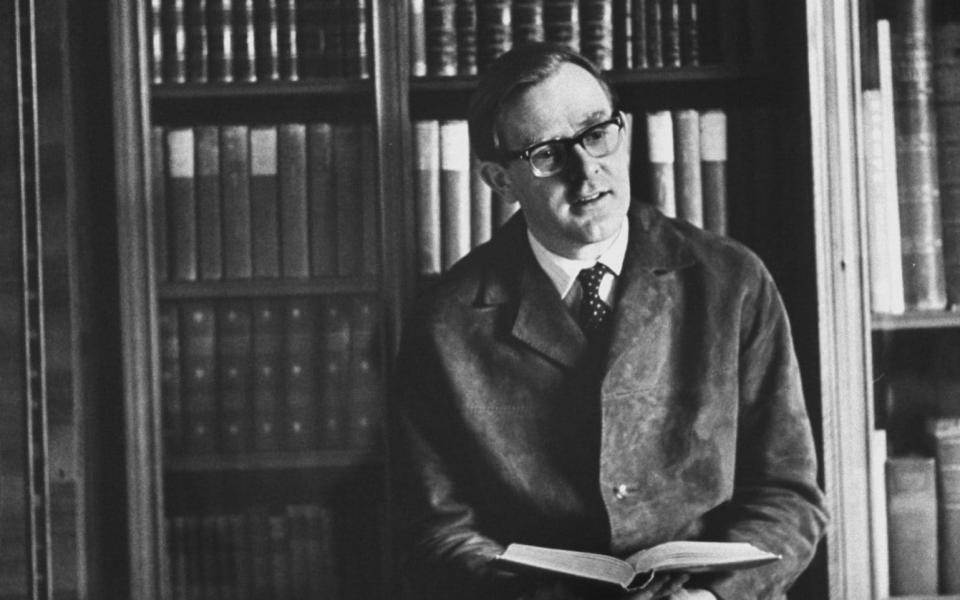

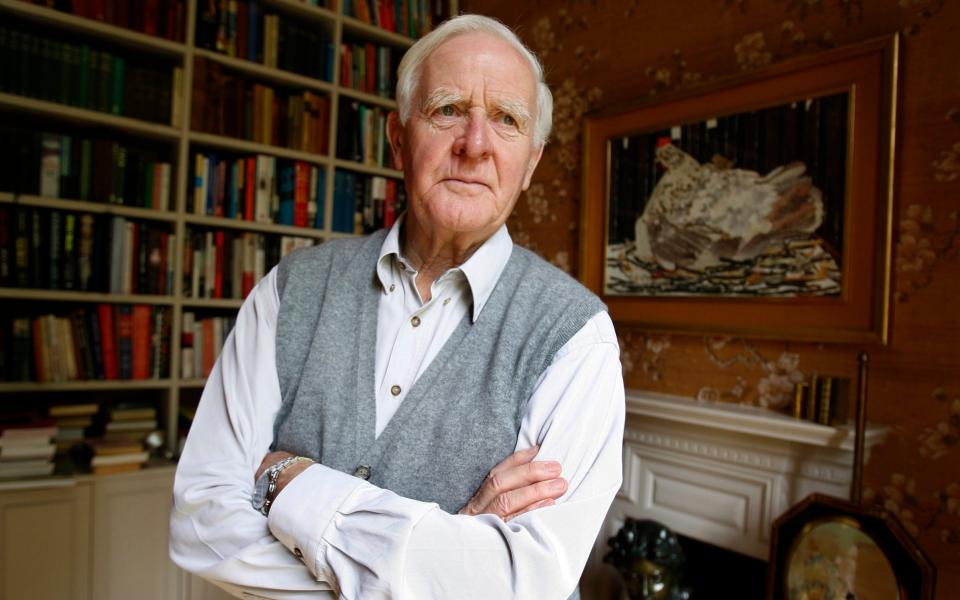

Speaking in 2017, John le Carré admitted he was “scared of being a bore” about his life. But the intelligence officer-turned-literary defector, who died at the weekend aged 89, was also forced to concede what some fans might call an understatement. “I've had, really, a very interesting life,” le Carré told NPR. “The strangest thing, in some ways, has been the cross-border relationship I’ve had with the former Soviet Union.”

The “most unforgettable event” in that peculiar relationship happened in October 1997: le Carré being summoned to dinner with the Russian Foreign Minister, Yevgeny Primakov, who was also the former head of the KGB and Prime Minister of Russia.

It began with a call from le Carré’s agent, requesting that he send a signed book to British Foreign Secretary Malcom Rifkind (and quickly) so that Rifkind could present the book to Primakov. It transpired that le Carré – writer of Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy and creator of spymaster George Smiley – was the Russian official’s favourite author.

That night, le Carré and his wife dined with Primakov at the Russian Embassy in Kensington Palace Gardens. Primakov told le Carré about his futile efforts to prevent the Gulf War, which he’d done at the request of his “friend” Saddam Hussein. But neither George Bush Sr nor Margaret Thatcher could be talked into a peaceful resolution.

News reports about the le Carré-Primakov meeting referred to Primakov as the “real-life version of Smiley’s arch-enemy, Karla”. But when asked later which character in le Carré’s books he most identified with, Primakov answered: “Why, George Smiley, of course!”

Primakov’s admiration for le Carré and kinship with Smiley speaks to the ambiguity at the greyed heart of le Carré’s espionage novels: British and Russian intelligence stand apart, staring back like murky reflections of each other. As le Carré said himself, he did have a strange relationship with the Russians: they both denounced and revered him; his novels were offered as essential reading to KGB trainees.

The British Secret Service was less impressed with the books. His real name was David Cornwell and he worked for MI5 before transferring to MI6 in 1960. He adopted the pen name “John le Carré” to protect his identity while still working for MI6. His books were also vetted by the intelligence agencies.

The Spy Who Came in From the Cold – his third novel and breakout bestseller – was passed for publication because, according to le Carré in 2013, “they seem to have concluded, rightly if reluctantly, that the book was sheer fiction from start to finish, uninformed by personal experience, and that accordingly it constituted no breach of security.” But the world’s press convinced itself the book was absolutely authentic: a true-life account from inside the Secret Intelligence Service. The author said that British intelligence later “kicked themselves” for approving the book.

Some in those agencies accused him of disloyalty. As recalled in Adam Sisman’s biography of le Carré, the head of MI6 Dick White reportedly complained to a US intelligence pal. “John le Carré hasn’t done us any good,” said White. “He makes all intelligence officers look like philanderers and drunks. He’s presenting a service without trust or loyalty, where agents are sacrificed and deceived without compunction.” Le Carré’s former mentor John Bingham said: “I deplore and hate everything he has done and said against the intelligence services.”

In 1964, le Carré resigned from MI6 to become a full-time writer. He dubbed himself a “literary defector” – along with the likes Graham Greene – but preferred to not be branded a “spy-turned-writer”. Rather, he was a writer who “had done a stint in the secret world”. He often claimed that he had to leave because his identity had been betrayed by Kim Philby, the notorious double-agent who defected to the Soviets. Philby, so le Carré said, passed his name to the Russians.

In October 1965, Moscow’s Literary Gazette demonised le Carré for being a Cold War apologist. The following year, le Carré replied with an open letter in Encounter magazine, titled ‘From Russia, with Greetings’ (this was just three years after Bond’s second cinematic adventure From Russia with Love).

As le Carré wrote in his memoir, The Pigeon Tunnel:

Ever since The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, I had been the target of Soviet literary invective, one moment – as my critics put it – for elevating the spy to heroic status, as if they themselves had not made an art form of doing exactly that, and the next for making the right perceptions about the Cold War but drawing erroneous conclusions, a charge to which there is no logical response. But then we were not talking logic, we were talking propaganda. From the trenches of the Soviet Literary Gazette, controlled by the KGB, and Encounter magazine, controlled by the CIA, we dutifully lobbed our bombs at each other, aware that in the sterile ideological war of words, neither side was going to win.

Indeed, he described his relations with the Soviets as being “less than friendly” for the best part of 25 years. Only two of novels were permitted for publication there – A Murder of Quality and A Small Town in Germany. But le Carré planned to visit the country in 1987 (for the first time), to research his upcoming novel The Russia House.

As detailed in Sisman’s biography, le Carré sought the help of John Roberts, director of the Great Britain-USSR Association. Roberts wrote in his diary that “selling the Soviets the idea of a le Carré visit is not proving easy”. According to le Carré’s own account, the deal to approve his visit was apparently brokered by the British Ambassador and Raisa Gorbacheva – wife of Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev – “over the heads of the KGB”.

He visited as “the guest of the Union of Soviet Writers”, but his reception was characteristically cold. His suitcase was held for 48 hours but suddenly reappeared in his hotel room. The Soviets had insisted he stay at the Hotel Minsk “where ageing microphones were permanently in place and a redoubtable female concierge kept guard over the corridor.” His room was searched whenever he ventured out, and two men followed him everywhere. One night, le Carré boozed with the dissident journalist Arkadi Vaksberg and (after Vaksberg had passed out on his own floor) emerged so drunk that he found himself lost on the outskirts of Moscow. His followers had to show him the way back to the hotel.

But le Carré found the Russians to be intelligent, cultured, and sympathetic. “Nobody who visits the Soviet Union in these extraordinary years, and is privileged to conduct the conversations that were granted to me, can come away without an enduring love for its people, and a sense of awe at the scale of the problems that face them,” he wrote in his foreword to The Russia House.

During the visit, le Carré and John Roberts attended a drinks reception, where he met Genrikh Borovik, a journalist with KGB connections. Borovik invited le Carré to meet “an old friend and admirer” over a glass of wine – the long-since defected Kim Philby. But le Carré refused to meet him. “It was a horrific suggestion,” le Carré said in 2010. “I told [Borovik] I was meeting the British ambassador next. I couldn’t see the Queen’s ambassador and then see the Queen’s traitor.”

As he wrote in The Pigeon Tunnel:

The scale of Philby’s betrayal is barely imaginable to anyone who has not been in the business. In Eastern Europe alone, dozens and perhaps hundreds of British agents were imprisoned, tortured and shot. Those who had not been betrayed by Philby were betrayed by George Blake, another MI6 double agent.

He continued: “Has my animosity towards Philby mellowed over the years? Not that I’m aware of.”

While in Moscow le Carré discovered a secret fan base while attending an assembly of university students. After a formal Q&A – “What do you think of Marx and Lenin, please?” asked one student. “I love them both,” he quipped, earning a riotous round of applause – the students smuggled him into a common room. They asked questions about a novel of his that he knew for certain was banned. The students revealed they’d read the novel in their “private book club”.

“Our team has typed out text of your book from illicit copy given us by one of your countrymen,” a student told him in stilted English. “We have read this book together at night-time many times. We have read many forbidden books in this manner.”

They also showed him a television set, on which they secretly watched a video of Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy. He described the encounter as “one of the most moving moments of my life”.

The contrasting reactions to him in Moscow summed up the overall relationship. “It appeared entirely logical to me, in the looking-glass world I had entered, that while I was being watched, followed and regarded with the heaviest suspicion, I should also be treated as an honoured guest of the Soviet government,” he wrote.

At some stage, le Carré discovered that his books were required reading at KGB training schools. “It was not my intention at all,” le Carré told NPR. “But they saw some kind of equivalence. You know, in the end – and it applies to doctors, scientists, and it applies to spies – people who are using the same techniques, developing the same techniques, who have the same attitude towards human beings, who put expediency and outcome over method, they are a brotherhood or sisterhood… the moment I get together with some retired general from the Mossad, I find we understand each other very quickly.”

In 2008, Rod Liddle interviewed le Carré for The Sunday Times, while le Carré was publicising A Most Wanted Man. Liddle reported that le Carré had once considered defecting to the Soviets – a story that was picked up and circulated worldwide.

“Well, I wasn’t tempted ideologically,” le Carré was reported to have said. “But when you spy intensively and you get closer and closer to the border… it seems such a small step to jump… and, you know, find out the rest.”

But le Carré then wrote a lengthy letter to the newspaper, saying he had been misrepresented. “I painted for Mr Liddle the plight of professional eavesdroppers who identify so closely with the people they are listening to that they start to share their lives,” he wrote. “It was in this context that I made the point that, in common with other intelligence officers who lived at close quarters with their adversaries, I had from time to time placed myself intellectually.”

He blamed the misrepresentation, rather generously, on Liddle taking handwritten notes instead of using a tape recorder, and booze. “He must be forgiven therefore if, while he too was sipping post-prandial Calvados in the evening darkness he describes, he failed to encompass or indeed record the general point I was making about the temptations of defection,” said le Carré.

The success of John le Carré’s novels has often been attributed to his humanising of intelligence operatives. Unlike the more fantastical James Bond, le Carré’s George Smiley was a frumpy bureaucrat; similarly, le Carré saw a more human side to the Soviets – an explanation perhaps, for the affinity that some Russians felt with him.

“Certainly, in communist times, there were bits of the KGB that were very, very decent, very humanitarian,” le Carré told NPR. “They took in persecuted people and protected them. They were a cult for themselves. They prided themselves on cultivating intellectuals.

“That was the rare decent part of the KGB. But it was such a big and powerful institution… There were a lot of rooms in it – [a] lot of different people.”