Can This $85,000 Watch Revive America's Great Watchmaking Tradition?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

This story was featured in The Must Read, a newsletter in which our editors recommend one can’t-miss GQ story every weekday. Sign up here to get it in your inbox.

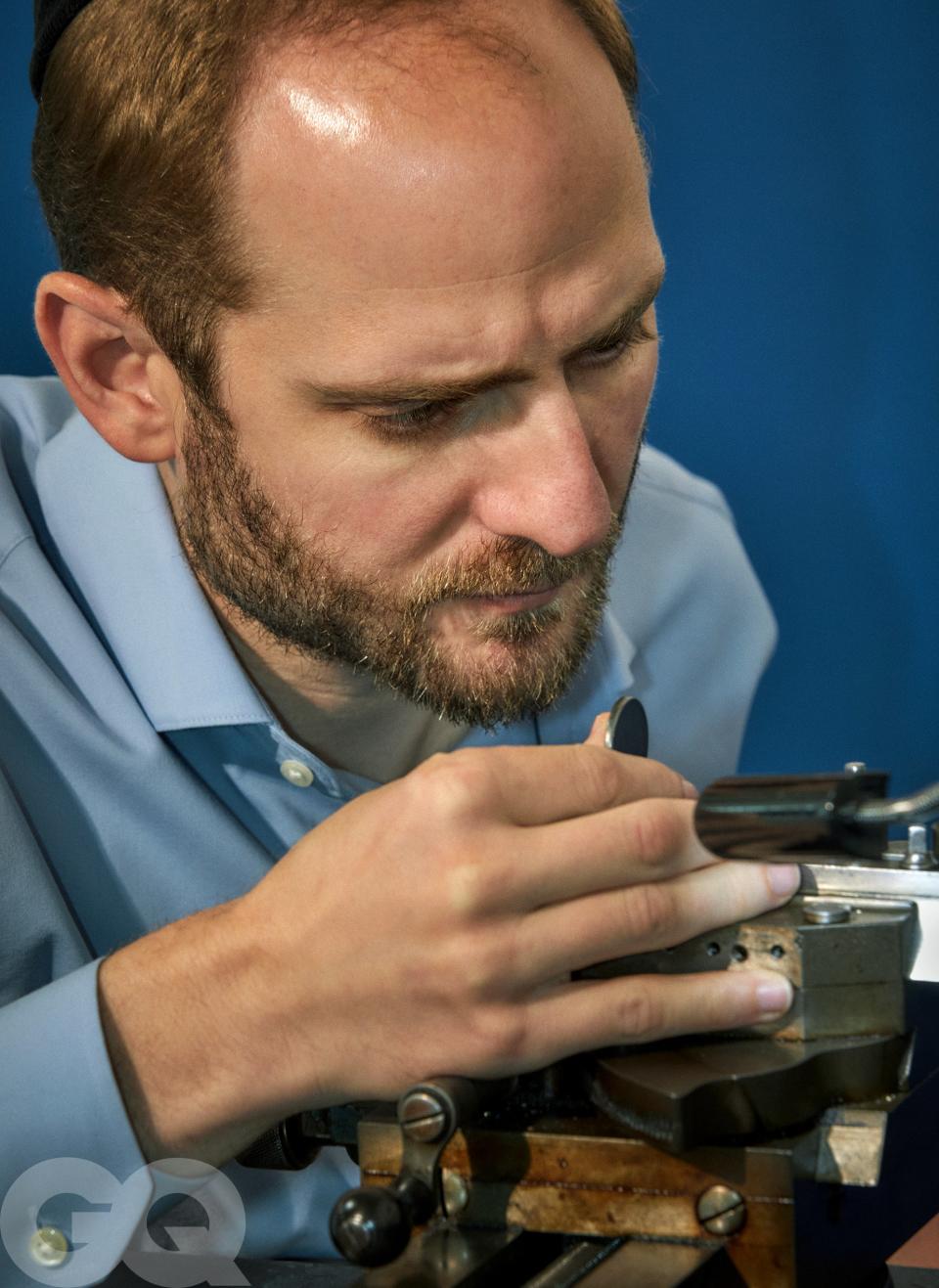

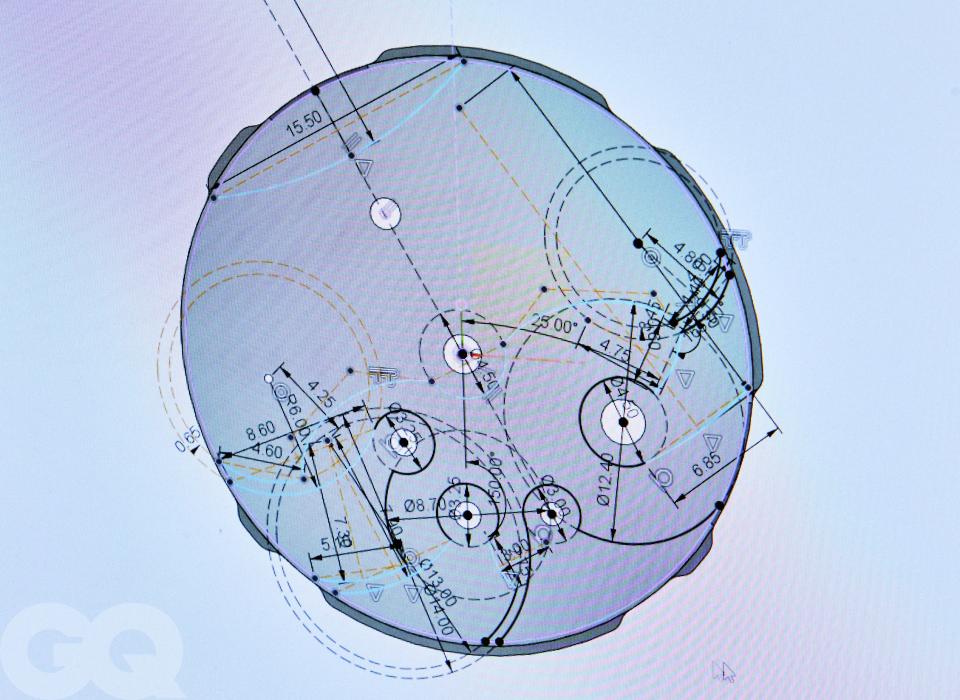

Michael Rose, a watchmaker for the Los Angeles–based J.N. Shapiro, is zooming in on a pinion—a round gear with tips as thin as a human hair—on his computer. That’s when I notice the skateboard propped up against his desk. Rose isn’t practicing his kick flips at work. Instead, he uses the board to zip around J.N. Shapiro’s sprawling 7,300-square-foot office—from the Ping-Pong table in the back to the old-fashioned engine turning machines up front.

Josh Shapiro, the brand’s 38-year-old founder, launched his namesake brand in 2018 after he began tinkering with watches in his kitchen nook, arranging his burgeoning collection of watchmaking machines around the dining table. A couple of years later, he moved into his first office—a rundown house with a garage—before eventually springing for a small studio. Last August, however, J.N. Shapiro took roost in this sparkling new facility that’s double the size of its previous headquarters. The vast digs are a signal of the recent growth—and ambition—of America’s long-dormant watchmaking tradition.

In May 2023, J.N. Shapiro debuted its latest model, the Resurgence ($85,000 in gold and $70,000 in steel), with a spectacular claim: According to Shapiro, the watch is made entirely in America. If true, it’s the first watch to fit that description in over five decades—since Hamilton produced its last timepiece at its Lancaster, Pennsylvania, factory in 1969. That long gap is in part due to the FTC’s prohibitively high bar for what qualifies as “American made.”

“Ninety-nine percent of all Swiss brands wouldn't be able to label themselves ‘Swiss made’ if they had the same rules as the US,” Shapiro said. Still, “the law is the law,” said Nicholas Manousos, the executive director of the Horological Society of New York and an expert on the history of American watches.

Between a burgeoning independent scene and a new wave of fun big-brand timepieces, 2023 was a stellar year for watches. But, arguably, no other recent release can match the weight of Shapiro’s Resurgence. It has the opportunity to serve as the spark plug for a presumed-dead domestic industry, carrying the burden of five squandered decades on its shoulders. Manousos compares Shapiro to George Daniels, the late British master horologist who famously constructed his watches entirely by hand—a process now known as the Daniels Method—and resuscitated the UK’s watch industry in the process.

The Lost American Art

“Compared to Switzerland, the American watchmaking industry was, by many statistics—watches made, watches sold—a bigger industry,” said Manousos. In the 1850s, Aaron Dennison, who would go on to found the Waltham Watch Company, created a system that revolutionized the watch industry. Manousos calls it simply the American system of watchmaking. Up to that point, each of the many pieces inside a watch were fitted specifically for every individual timepiece. Dennison set out to create standard-size components so that when something broke, a technician could easily order a replacement. This simple advancement increased manufacturers’ efficiency and enabled American-built watches to flourish.

Simple watches are a hallmark of the American industry. Manousos compares timepieces back then to cars now: They were vital for navigating daily life. And much like Henry Ford, American watchmakers specialized in producing affordable and reliable products. The ability to produce pieces at a much higher clip helped stateside companies like Hamilton, Bulova, Waltham, and Elgin outmaneuver their Swiss counterparts in the early 1900s.

That all changed during World War II, when watch manufacturers were required to bolster their efforts overseas. Domestic factories pivoted from producing tiny hairsprings to ammunition and bomb timers. In the meantime, neutral Switzerland continued to make and market watches. “After World War II, it was very difficult for the American brands to restart their watch production,” Manousos said.

“The Swiss worked very hard to take over the US market,” Shapiro said. Hamilton, the last standing American watchmaker, was absorbed by the Swatch Group in 1971. The factory closed its door that year and employees were forced to dispose of the parts. “Then a bunch of watch collectors and people that cared went to the dump and saved as much as they could,” Shapiro said.

A Difficult Process

On the day of my visit, four employees cloaked in white lab coats sit in deep concentration tinkering in front of lasers or salad-plate-size magnifying glasses (JN Shapiro employs nine people, including Josh). But antique machines similar to the ones that would have been in the Hamilton factory sit at the front of Shapiro’s immaculate facility. Shapiro guides me over to his collection of nine engine turning machines, his favorite equipment in the studio, which the brand’s watchmakers still use today. His collection includes ones from before World War I, accumulated through local jewelers, friends in Switzerland, and machine auctions. He also owns machines from LA’s own A.J. Levin Company, which pivoted from developing watchmaking machinery to aerospace equipment in the 1960s as demand for the former faltered. These machines stamp a pattern on a dial and require a steady hand to operate—one wrong move means a watchmaker has to start over completely. At the start of my visit, Rose held out his own stunning emerald version of Shapiro’s now-discontinued Infinity model that he finished in his spare time after one of Shapiro’s watchmakers made an error imperceptible to the average person.

But Shapiro also called in new tech to help him make the Resurgence. The most important contributor is the CNC machine, a shed-size box that looks like it could double as a time machine. It has a hollow center and roughly a bajillion buttons on the exterior panel. It cost Shapiro half a million dollars. The machine’s role is to produce microscopic parts like pinions and mainplates, but programming the CNC machine to make them requires more training than you need to become a commercial pilot. Shapiro employs a dedicated CNC operator named Daniel, who went to school for two years just to learn how to operate the machine. I think about the CNC machine when Manousos tells me why there are no other timepieces made completely in America: “It's very difficult to make a watch,” he said. “It really comes down to two or three specific parts that are incredibly difficult to manufacture: the hairspring, the jewels, and the pinions.”

Mainspring, USA

“If I wanted to go out of business, manufacturing mainsprings would be the quickest way to do it,” said Roland Murphy of RGM, a watch brand based in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. RGM has been building timepieces out of a former bank building there since 1992, and Murphy says about 90 percent of the components are made in America. If he were operating in Switzerland, he would have long surpassed the requirement to label his pieces “Swiss Made.” He’s proud of this standard: “These are watches that we actually produce and have sold many to actual customers,” Murphy said. (Not even Shapiro makes his own mainspring—he argues it qualifies as an easily replaceable battery, which doesn’t disqualify the Resurgence from Made-in-America status.)

One challenge in repopulating the American watch industry is the lack of US-based part suppliers. According to Murphy, unlike in Switzerland, there are no manufacturers stateside that produce mainsprings or anti-shock systems. Still, there is a small crop of other American-based watch brands that include Keaton P. Myrick, David Walter, and Weiss Watch Company, the latter of which had its own run-in with the FTC over the governing body’s stringent interpretation of “Made in America.”

The challenge of making watches stateside is part of the allure for collectors who come to RGM and Shapiro. “I think it’s important to do things here,” Murphy said. “I know my customers want that.”

The Shapiro Way

In Shaprio’s still-unpacked office, boxes of watchmaking books—like Michael Clerizo’s Masters Of Contemporary Watchmaking—are stacked on the floor. Shapiro explains that his passion for American-made watches stems from his background in academia—he’s earned both his undergraduate and master’s degrees in history, and was working as a school principal when he started making dials for David Walter on the side.

J.N. Shapiro follows the history of the American brands that came before them. While Swiss brands source components from manufacturers around their home country, the famed American makers famously crafted their watches fully in-house. “There were these huge factories where they made every single part of a watch, so that’s the holy grail of watchmaking,” Shapiro says. “That was always my goal: Build a watch from scratch in one place.”

Despite being the first made-in-America watch in over 50 years, Shapiro’s Resurgence doesn’t rest on those laurels to move stock. The watch itself is beautiful, with multiple patterns engraved across the dial, the case, and even the movement—putting Shapiro’s beloved engine turning machines to work. The benefit of controlling every step of his production is that he can customize a piece to a client’s exact wishes. White gold is the most popular choice, but J.N. Shapiro can also make watches in rose gold, tantalum, zirconium, and steel. Examples on his website depict far-out color combinations like black dials and purple numerals. American watchmaking history instructs the look of the movement too, which is finished with a wavy pattern known as damaskeening, the most famous aesthetic signature of the US’s horological heritage. The pattern represents America’s equivalent to Switzerland’s Côtes de Genève.

Shapiro has sold 54 Resurgence pieces so far. As of November, Shapiro said he is on track to deliver the first watch in February 2024. He plans on producing the rest of the orders over the next two years, making about 30 per year. The new Resurgence pieces will be the first American-made watches to come into the world in more than half a century.

When Shapiro debuts his next watch, he’ll tilt his sales pitch away from the American-made messaging and toward attributes like high-level finishing. While he gained domestic customers looking to rejuvenate our moribund watch industry with the Resurgence, he lost international buyers who weren’t drawn in by the patriotic marketing. For Shapiro, even his clients are made in America.

Want more insider watch coverage? Get Box + Papers, GQ's newsletter devoted to the watch world, sent to your inbox every Friday. Sign up here.

Originally Appeared on GQ

More Great Stories from GQ

Saltburn's Barry Keoghan on Flirting With Jacob Elordi and Manifesting Stardom

How Jeremy Allen White Prepped for His Calvin Klein Underwear Campaign

Why True Watch Heads Never Set the Time on Their Watches

How Zac Efron Bulked Up for His Wrestling Debut in 'The Iron Claw'

Not a subscriber? Join GQ to receive full access to GQ.com.